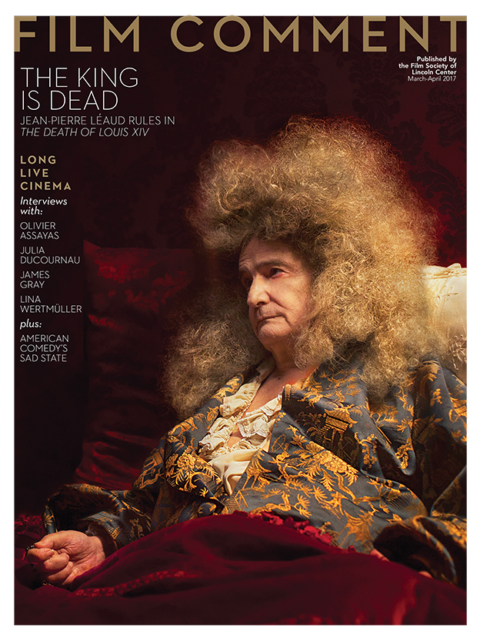

By Violet Lucca in the March-April 2017 Issue

No Joke

Out of touch and rehashing ideas, is American comedy simply circling the drain?

Comedies were never made for critics, but what’s changed, I think, is that the new comic style is objectively hostile to most of the established critical values. Comedies now flaunt their arbitrary organization, their thinness of character, and their lack of content—almost as if they were trying to keep intellectuals out…[The intellectual] hates its lack of subtlety, because without subtlety there is nothing to explicate. He hates its lack of content, because without content there is no copy. Comedies aren’t smart anymore—not the way they used to be when Keaton was making his mechanical ballets, when Cary Grant was pointing his finger and cracking wise, or when Preston Sturges was stuffing his frame with sociological observation. Nowadays comedies are stupid—and strangely enough, they seem proud of it … because comedy is no longer a game for filmmakers, either.”

—Dave Kehr, Film Comment, July/August 1982

From the March-April 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

We know the joke that came after the Obama administration, and it isn’t funny: a reality-show entertainer in the White House who ran a campaign by skillfully manipulating the news cycle and social media. But while the news media has long sought to integrate itself with entertainment and the 24-hour rhythms/reacts of the Internet (to the point that the news and Internet culture are basically indistinguishable) in order to cater to viewers, American comedy too has undergone drastic changes over the past eight or so years that reflect new industrial realities of Hollywood—and Washington, D.C. These include the way in which films are made, how they are expected to perform, and where talent is being pulled from, which in turn have impacted the content and form of comedies. (Because films are not something neatly wished into existence, I will define the “Obama-era comedy” as films released between 2010 and now.) Television and Internet video have usurped film as the preferred destination for aspiring comedians to practice their craft and achieve fame, as they offer greater creative control and more opportunities to be timely and trendy.

The most acute of these changes is Hollywood’s intensified focus on global markets: domestic performance alone cannot justify a multimillion-dollar budget, especially when a film is competing for attention against television, the Internet, VOD, and video games. The specificity of wordplay and sociological observation—two things that non-silent comedy thrives on—is therefore diminished or omitted to ensure its international portability. (Woody Allen is an outlier in this regard, although judging by the tepid jokes on display in Café Society, he isn’t capable of or interested in bon mots like “Commentary and Dissent merged and formed Dysentery” anymore. Well, la di da.) What has come to replace it is meta-commentary on genre convention and generalized anxieties about modern life (work) or universal rites of passage (marriage, parenting), borrowing from the Apatow template of losers just barely growing up by the film’s close.

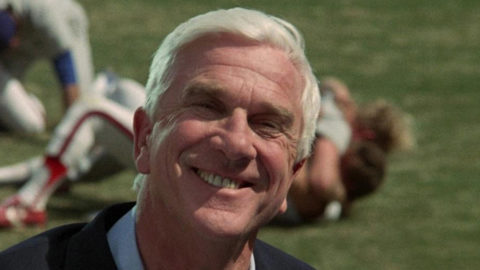

22 Jump Street

In the category of genre play, we find reboots, sequels, and product placements such as the 21 Jump Street films (Christopher Miller and Phil Lord, 2012 and 2014), the nascent LEGO Movie franchise (Miller and Lord, 2014; Chris McKay, 2017), Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues (Adam McKay, 2013), and Ghostbusters (Paul Feig, 2016). Per Adam McKay, a founding member of the Upright Citizens Brigade, former head writer of Saturday Night Live, and cinephile, much of the comedy in these films comes from “making fun of the fact we’re making a movie.” 22 Jump Street opens with a montage that begins with “Previously on 21 Jump Street,” pointing to the fact that this franchise was originally a TV show with cut-to-commercial cliffhangers, and underlining that we’re watching a sequel; soon after, Captain Dickson (Ice Cube, in a bit of reflexive casting) lists a series of possible outcomes (all movie sequel clichés) for undercover duo Schmidt and Jenko’s second mission, and notes how much more money is available to spend on it because their first was so successful. In The LEGO Movie, many of the meta jokes call attention to and undercut its “regular guy who turns out to be The Chosen One” plot; in This Is the End (Seth Rogen and Evan Goldberg, 2013) and Sausage Party (Conrad Vernon and Greg Tiernan, 2016), celebrity cameos and fourth-wall breaking endings call into question the nature of reality; Anchorman 2 and Zoolander 2 winkingly incorporate “getting the gang back together” story lines and repetitions of successful gags from the Bush-era originals (the news-anchor fight and Wham!’s “Wake Me Up Before You Go-Go” respectively). These tropes cumulatively function as what philosopher Robert Pfaller has termed “interpassivity”: they cynically perform our annoyance at seeing the same old thing again for us. We can walk out of these films feeling satisfied, refreshed, and maybe even a little superior for seeing how the mechanics of movies work. And yet, this facsimiled dissent does not result in movies with original ideas, but instead in things like The LEGO Batman Movie, or, say, Miller and Lord helming the forthcoming Han Solo movie. Not unlike a punk buying a T-shirt with an anarchy symbol on it from Hot Topic, we fool ourselves if we believe this humor to be as subversive as it pretends to be.

It would be foolish (and very limiting) to say that tearing The System down must be the raison d’être of a good joke, but from medieval carnivals to Keaton’s The Cameraman, there’s always some amount of subversion of the social order or expected convention. In the post-sound era, the subversion took forms that responded to the times: screwball comedies like Bringing Up Baby and The Awful Truth reflected changing ideas about marriage as well as new economic realities; the coziness and conformity of postwar American life was first sent up with The Seven Year Itch and Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, then transformed into more openly anarchic confrontations like Lord Love a Duck and Dr. Strangelove. Soon after, comedians who came up through stand-up and/or television-writing wrapped their critiques inside their (second-generation Borscht Belt) personas in films like Where’s Poppa? and Blazing Saddles. In the 1980s and ’90s, as conservatism had a resurgence and was put into practice through privatization and tax cuts, cult-of-personality comedians were less likely to dissent openly with the “political.” More commonly, anxieties about gender/gender roles (Tootsie, the Look Who’s Talking films) and race (Beverly Hills Cop) were dramatized, though self-reflexive jokes and genre mash-ups became more common (usually starring Saturday Night Live alumni), like The Blues Brothers (1980), the original Ghostbusters (1984), Wayne’s World (1992), and the Naked Gun (1988-1991) films. Another angle was the self-referential world of Kevin Smith’s View Askewniverse, which blended the verbiage of indie film with nerdy pop-culture references.

Remakes and adaptations of successful, preexisting intellectual property are nothing new—they have been part and parcel of Hollywood since its inception. However, as the media scholar Mark Fisher suggested, “capitalist realism” resigns us to this repetition by telling audiences that we are in crisis mode and there’s no time to think about anything outside of the current system: Hollywood really is out of ideas this time, so just get used to it. It is the seventh art acknowledging its marginalized state and throwing up its hands. The marketing of Ghostbusters attempted to use a different type of crisis to sell tickets—some misogynists on the Internet were rejecting the film before it opened—but alas, the film wasn’t terribly funny or feminist. Perhaps the strongest evidence for Fisher’s thesis is the dwindling supply of comedies and conspicuous absence of rom-coms—those that do exist tend to incorporate action and/or doomsday plots, following the formula of the original Ghostbusters. Across every comedy, the party sequences look and sound the same (Icona Pop’s “I Love It” has officially achieved Katrina and the Waves’ “Walking on Sunshine” status), and the third-act car chases/mass mayhem inevitably happen at the same time—even the moments of release are prescribed and formulaic.

Anchorman 2: The Legend Continues

But this isn’t to say that these disaster-courting comedians are talentless or unfunny. Quite the opposite: Jonah Hill is incredibly adept at comedy and drama, the undeniable sweetness of his face never telegraphing emotions too hard, as he brings nuance and charm to something as tone-deaf as War Dogs (Todd Phillips, 2016); Will Ferrell brilliantly modulates the intensity of his delivery and generates fiercely hilarious one-liners to bless the otherwise unfunny Zoolander 2 (2016). Lord and Miller, just like McKay, understand how to construct jokes and compose scenes: their scripts never drag or go too fast, and they know when to let their (highly skilled) performers loose to improvise. (And, unlike Paul Feig, Judd Apatow, and Mike Birbiglia, they don’t lean too heavily on test audience-approved punch lines.) These directors also excel at “heightening” (adding information/emotion to a scene) and raising the stakes. In Anchorman 2, Ron Burgundy and his fellow San Diego anchors drive up the ratings of a fledgling 24-hour news network, shown in a giddy montage that culminates with the boys smoking crack live on-air. The sequence begins innocently enough, with Ron delivering a benign, “gee-whiz” intro directly to the camera befitting any dopey trend piece (“…and it costs about as much as a soda pop at the local drugstore!”). Using camerawork and editing conventions that all news programs use (switching between cameras one, two, and three), McKay adds the anchors to the scene one by one, a choice that highlights their individual personalities and slowly ramps up the chaos. (Steve Carell’s Brick Tamland, standing in front of his weather map, declines to join in because he’s afraid of fire.) As the anchormen revel in smoking up, McKay breaks the aforementioned shot conventions and we see what Ron and company are doing; the rest of the crew desperately tries to get them to stop (without actually yelling at them, because that would break on-air set rules). The sequence ends with the anchors handcuffed and lying face down on the glistening Manhattan pavement, as the police let them go with the warning not to smoke crack on television again. (This slap on the wrist is a nice final joke—or “button,” to comedy writers—but doubling as satire, it also points to the way in which rich white men are treated when caught with drugs.)

In lesser hands, heightening and raising the stakes can go awry, or just nowhere very funny. Much of the comedy of Bad Moms (Jon Lucas and Scott Moore, 2016)—a film that is predicated on the very real, paralyzing fear mothers have about being not good enough to their kids (and being judged by others for it)—falls flat because it starts from an unbelievable place, pushes only some details to their extremes (not really abiding by an “if x, then y” logic), and lurches forth with its plot. After a particularly bad day at her millennial-infested job (her first solo after kicking her brain-dead, cam-girl-lovin’ husband out), Amy (Mila Kunis) arrives late to a PTA meeting presided over by the domineering, rich, ultra-perfectionist Gwendolyn (Christina Applegate). Gwendolyn struts onstage in front of her presentation about the upcoming bake sale, which uses stock footage of explosions and riots to emphasize her seriousness. Yet rather than do anything with this absurdity, the rest of the scene just involves Amy “standing up” to Gwendolyn and telling her how bad her day has been, the other mothers gasping en masse off screen. (Presumably they’re gasping because this is an affront to the mom hierarchy—or maybe it’s just a failed attempt at heightening.) None of Amy’s confrontations with Gwendolyn are funny, but rather serve to re-emphasize what a bitch the latter is. A later scene starts more promisingly: when Amy tries hitting on guys at a bar for the first time in years, she offers them momly advice, scaring them all away. But when she finds a hot dad whose kid goes to the same school as hers, the brief moment of authenticity evaporates: he’s far too perfect, and she ends up head-butting him when she goes in for a kiss. (Who knew that being a mom messed up your spatial perception so thoroughly?)

This sort of tepid approach—absurdism that’s not employed to any more meaningful end—runs throughout many “death of the movie title” films: Horrible Bosses (Seth Gordon, 2011) and Horrible Bosses 2 (Sean Anders, 2014), The Watch (Akiva Schaffer, 2012), Sex Tape (Jake Kasdan, 2014), Neighbors and Neighbors 2: Sorority Rising (Nick Stoller, 2014 and 2016). These films largely follow a pattern established by the wildly successful, knowingly sexist/racist/homophobic Hangover films, which center on a group of three friends: the responsible one, the goofy and/or horny one, and the crazy one. (Sometimes a fourth, the black one, will join them.) Like Apatow’s early, reputation-making comedies—themselves conservative but charming emblems of the Bush era—they wrestle with the injustices that come with the roles each of us is fated to fulfill . . . like a horrible boss, horrible neighbor, or horrible spouse. Yet despite being rooted in these timeless struggles, and sometimes successfully depicting certain aspects of them, these films never get specific or focused enough to be truly insightful: Trainwreck (Apatow, 2015) has a surfeit of bad ADR one-liners and ends with a dance number involving the New York Knicks cheerleaders as “proof” that Amy Schumer’s character has grown up; Let’s Be Cops (Luke Greenfield, 2014) never bothers to do anything with its flimsy premise aside from announcing it and involving the Russian mob. Full of nothing in particular, these films’ late-second act pleas for pathos inevitably seem unearned: just because I can recognize a situation is intended to be touching, doesn’t mean I will empathize or end up caring about these not-so-lovable losers.

Let's Be Cops

Though they’re ostensibly for “adults” with their gross-out humor and themes, there’s nothing mature about the way in which these films operate. Instead of trusting their audiences to laugh by pointing out familiarity and formula, these films trade in some rather retrograde stereotypes: guys are dumb and can’t be trusted to do anything around the house, women who actually like to have sex are crazy nymphos, all black dudes are really tough and flashy, and gay men are constantly plotting to suck off a straight dude. Their settings are also conspicuously out of date, specifically pre–financial crash: Ben Stiller’s character in The Watch is a manager at a Costco in Ohio, and he lives in a giant house in a suburb—just like everyone in Sex Tape, Neighbors, Ted, and Bad Moms. Having achieved the American dream (without class, religion, or non-wacky immigrants ever coloring their experiences), what else could these white people have to worry about besides sex and optimal emotional fulfillment? Their jobs, nebulous or intentionally caricatured to avoid scrutiny, fail to reflect the increase in the “gig economy” and realities of part-time work. The closest that Hollywood film comedy has come to dealing with a post-crash world is The Internship (Shawn Levy, 2013), which is essentially a mash-up of Wedding Crashers and a commercial for Google. Internet comedy and television have responded much better—social-media star Joanne the Scammer is broke as hell and isn’t afraid to show it (and neither was Chaplin’s sentimentalized but soot-streaked Tramp).

The few comedies that tried to comment upon or insert humor into more serious situations didn’t succeed. The suspiciously similar trio of Iraq and Afghanistan War movies Rock the Kasbah (Barry Levinson, 2015), Whiskey Tango Foxtrot (Glenn Ficarra and John Requa, 2016), and War Dogs pair world-weary dark comedy with hookup culture and big gun fights in foreign lands, never daring to comment on the senselessness of war in general—let alone the ones they’re set inside. (They are also ceaselessly disrespectful toward Muslims and citizens of those occupied countries, as cultural differences provide a major source of comedic fodder.) In the domestic realm, there is Barbershop: The Next Cut (Malcolm D. Lee, 2016), which, as real-life barbershops often do, functions as an open forum for chewing over everything from Instagram hos to gun violence to Obama’s legacy. The film is ultimately dominated by a preachy, “this is the answer” tone—even though it includes a chase/action sequence in the third act, just as the first two installments do—so even calling it a comedy seems odd. Given how unnecessarily divisive gun violence is (and that people can affirm whatever opinion they already hold by referencing whatever media they prefer), it seems unlikely that comedies seeking to make larger or nuanced sociological comment on such issues will come out of Hollywood. And while it would be tempting to label the crasser, whiter, less self-reflexive comedies as “red-state films,” those aren’t the only places that want to make America great again, or laugh at gay men. Given the limitations and expectations placed on most films currently being produced, it’s probably for the best that comedies, to the extent they are allowed to continue to exist, will play it safe rather than be financially sorry.

Cinema seems increasingly ill-equipped to deal with the speed of everything else in contemporary culture—what was the first studio movie you saw that actually got something as basic as texting right?—and this only seems to deepen with time. (As Wesley Morris astutely noted in his review of Let’s Be Cops, the moment picks the movie more often than the other way around.) The easiest way to avoid this problem entirely is to do exactly what Hollywood has perfected over the past eight years: use generic formula and familiarity rather than cultural specificity to generate laughs. Robert Townsend’s superb Hollywood Shuffle (1987) would be unthinkable now (all the more so given studio loyalties, like the Disney/ Marvel CEO’s chummy relationship to the White House). However, if Hollywood tried the more difficult option—getting screenwriters who privilege sharp wordplay over referential meta-commentary and filmmakers who can stage physical comedy that’s more complex than an actress splashing spaghetti on her face while driving a minivan—we would have something built to last in an otherwise dispensable, instantly forgettable media environment. Until then, we’ll just see more stand-ups and improv veterans trying their darndest to keep their car under control during a madcap chase, and know that the film’s gonna end in about 15 minutes.