By Eric Hynes in the July-August 2018 Issue

Make It Real: Evidence of a Life

Wang Bing’s Dead Souls does justice to the few who lived to tell the tale of mass atrocity

Certain real-world horrors remain unfathomable, ungraspable, and seemingly impossible to capture on film. Systemic subjugation, torture, premeditated mass murder—the immensity of these horrors can feel beyond comprehension, even as we’re also aware that they’re not beyond human capability. The incomprehensibility can actually enable man’s abuse of man, in that the limits of our imagination become a shield against accepting or believing these realities. Relatedly, though there are still limits to what a camera can record, our visually mediated culture can make limitations harder to identify and tolerate. Since these days it seems like cameras can go anywhere and do anything, and that everyone has access to platforms on which to broadcast immediately what they capture, it can be difficult to accept that something might remain beyond the camera’s reach, or that the camera might bring us farther away from rather than closer to understanding.

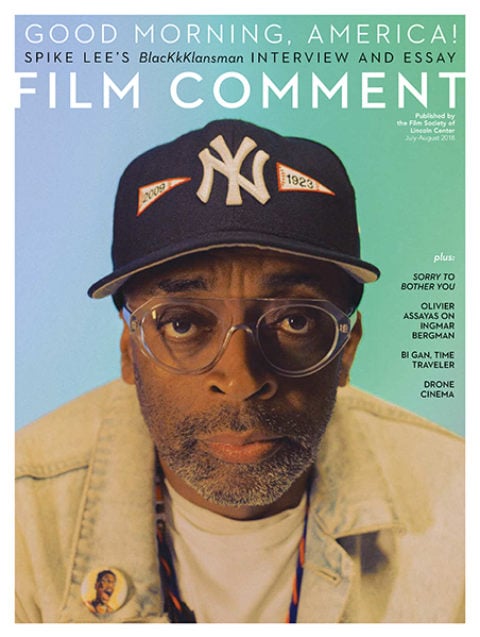

From the July-August 2018 Issue

Also in this issue

And so how to at least try to represent horror of this magnitude with this inadequate, even misleading tool? As Claude Lanzmann demonstrated in Shoah (1985), while there are limits to what the camera can (or should) show, it’s conversely effective at revealing what’s missing. Absent footage of the Nazi death camps, absent vintage snapshots, absent any veneration of lives that endured beyond the camps, the film becomes one long, detailed, traumatized testimony of what’s invisible to us and yet fully present, of what’s beyond the borders of the frame and yet heavily conjured within it. Lanzmann wasn’t documenting the genocides at the Nazi death camps, he was staring at their afterimage, surveying present-day rehabilitated landscapes for invisible but pervasive ghosts, asking us to do the haunting ourselves based on what we hear and understand to be true from eyewitnesses. He knew that the camera has a tendency to accommodate and normalize whatever it records, even that which it never should. By denying the camera’s full sight, refusing to make the Holocaust tangible in a way the audience craves, he preserves its appalling scale, its moral unacceptability, even while pursuing its evidentiary explication. He keeps the imagery in the present tense, where the past can’t be comfortably contextualized, its horrors muted by time difference, but rather where its effects are manifold, the horrors implicatively ongoing.

Shoah

Wang Bing pursues something similarly weighty and mindfully austere with Dead Souls, which premiered as an official selection at this year’s Cannes Film Festival, and is among the few films to ever merit comparison to Lanzmann’s project. Adopting a scale that’s nearly as epic as that of Shoah, Wang’s Dead Souls shines a bright and steady spotlight into a dark corner of 20th-century Chinese history—a corner the communist government continues to try to keep in shadow. Following a brief period of what seemed like self-reflection, during which comrades were encouraged to offer opinions and suggestions for furthering the revolution, in 1957 the Maoist regime began a punitive Anti-Rightist campaign in which men, often on specious and counterfactual grounds, were suddenly banished to a remote region in the northwestern corner of the country for “rehabilitation.” Forced into labor, denied adequate food, they were effectively left to die in the Gobi Desert. Of 3,200 men sent to the Jiabiangou work camp, only 500 survived. Starting in 2005 and continuing through 2017, Wang interviewed 120 of them. Just under 20 appear in the film, and most have since passed away.

Like Lanzmann, Wang largely avoids archival material (save for one epistolary exchange and a key set of stills), depending instead on the present-day testimonies of those who lived at Jiabiangou from the late 1950s through the early 1960s, and contemporary footage of the depopulated, deactivated site. With a runtime nearly as forbidding (496 minutes) as Lanzmann’s (566), its vast canvas is both earned and inverted by interviews that tend to be casually intimate and free-flowing. Often preferring a quietly dexterous handheld approach rather than locking off the frame with a tripod shot, Wang records the men mostly where they live. Sometimes accompanied by a silent spouse, they speak from futons, the kitchen table, even from bed, racing against time and struggling to find adequate breath to describe experiences about which they’ve hardly ever been asked. It’s accurate but a little misleading to even call these “interviews,” because though Wang can often be heard asking follow-up questions—and in one long exchange late in the film he actually appears on camera—they play more like monologues, long-delayed, extraordinarily detailed accounts of circumstances and living conditions that defy comprehension. The speakers don’t need to be coaxed or drawn out—Wang’s questions tend to be about clarifying and underscoring that which they’ve already said. Finally aged beyond caring about repercussions from the state, these men are emptying the tank for Wang and his camera, and the filmmaker wants to catch and process every drop. As sessions accumulate—some go on for 10 to 15 minutes, others for over 30—the lengthening film becomes essentially so, confirming and reconfirming the factuality of what’s being revealed. Dead Souls doesn’t tell a story, it gathers and presents evidence through a series of grimly harmonized personal narratives, inviting the viewer to not simply follow along but receive, reckon, and synthesize.

Dead Souls

“I wish they’d taken reality into account,” says Zhou Huinan, the first survivor to appear in the film. It’s a damning statement born of great suffering—like most prisoners at Jiabiangou, his life was destroyed for no good reason—yet also of resilience. Propaganda, misinformation, and bureaucratic nonsense may have been used to justify Zhou’s subjugation, but it doesn’t hold sway here anymore. The supposed Anti-Rightists were officially rehabilitated in the 1980s, but the men don’t give the impression that they were ever persuaded into believing they needed such rehabilitation, that the tragic surreality of what they endured had real cause. It’s one of the most powerful and sobering aspects of these testimonies—they stand not as a current, harsh-light-of-day corrective to a collectively accepted fiction, but as proof that reality proceeded throughout. When a regime loses its mind, when its people are denied their humanity, their autonomy, their freedom, when notions of a collective are used to conceptually negate individuality and literally murder individuals, those individuals still physically and emotionally remained, for however long they could manage to survive. They weren’t transformed into an idea, or melted down into an expendable mass. They adapted, they starved, they suffered. Wang introduces us to people who lived long enough that they could tell us how they were left to die.

By letting us hear each account in detail and at length—with time enough to memorize subjects’ faces and grow familiar with their speaking styles and physical quirks—Wang fends off our tendency to blend them together and depersonalize their experiences. He’s not letting us make them into a metaphor. He’s trying to prevent his own film from dehumanizing them any further. Taken together, their stories stand as irrefutable proof of an atrocity still denied, still talked around and down by the Chinese government. But they suffered personally, with bodies weakened and atrophied and bloated, left to live as savages scrounging scraps from passing trains, drinking their own urine, even consuming those who perished in their midst. Wang ends the film surveying the windswept desert landscape that is still a mass grave, alighting upon bones strewn on the ground in one unbroken shot. He does not pan across these bones to communicate a mass of them but instead finds frames through which to observe them, sometimes fixing for minutes at a time on a single bone or skull. There’s only so much these shots can do, there’s only so much information Wang’s camera can forensically and meaningfully absorb. But the concerted attention has meaning in itself. This shard was a person. This femur was a person. He wasn’t treated like one. He’s not even remembered as one. But look, please look. This was a person.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and curator of film at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.