By Eric Hynes in the July-August 2017 Issue

Make It Real: Give and Take

Laura Poitras’s Risk and Mark Grieco’s A River Below grapple with trust and truth

Where were you when I was there, fucking myself? Where were you? Doing what?” the subject asks, thrusting his finger so far toward the unseen filmmaker that it moves out of focus. The moment comes halfway through the knotty new documentary A River Below, which premiered at the Tribeca Film Festival in April. It’s a film that comes on as an activist exposé of illegal slaughtering of the Amazon’s endangered pink river dolphin, then turns into an ethical hall of mirrors. Suddenly the supposed bad guys are revealed to be impoverished can’t-win middle men, while the tactics of wildlife defenders like the speaker of the above quote, Richard Rasmussen, a biologist and gregarious celebrity host of a popular show on National Geographic Brazil, get rigorously questioned. With the camera trained on his surprised reaction, director Mark Grieco and crew confront Rasmussen with charges of betrayal by local fishermen who’d participated in a dolphin killing that the host recorded and aired on national TV. He appears contrite, but also parries and denies the charges, eventually ending the interview. “Is this a trick?” he asks.

From the July-August 2017 Issue

Also in this issue

A few short scenes later, the filmmakers return for a follow-up, and Rasmussen bristles over having been blindsided. “For the last three days, you’ve been around my house, my family, my life, and I completely gave myself,” he says, alternating his gaze and barely concealed rage between his interlocutor and the camera. “I told you—ask anything, I have nothing to hide… But I was surprised by you guys having information that you didn’t share,” he says. “And man, that pissed me off.” The exchange functions as the film’s turning point, decidedly recasting the issues in play, but the scene’s essential tension also echoes beyond the Amazon, and with other films in which the connection between director and subject is dramatically disrupted.

In documentary, the relationship between filmmaker and subject is a precarious one. It involves both mutual trust and mutual exploitation. The filmmaker needs the subject to reveal him- or herself, while the subject needs the filmmaker to represent him- or herself, and to do so accurately and fairly. The filmmaker takes advantage of the subject’s candor, turning self-presentation into cinema, while the subject takes advantage of the filmmaker’s interest, turning attention into exhibition. The filmmaker turns the subject into a character, and then the character absorbs the spotlight. At no point is any aspect of their connection, chemistry, comfort, or collaboration fixed. The relationship, as with any relationship, is contingent. Except it’s also unlike any other relationship in that its contingent nature is affixed to, and defined by, a tangible reflection of itself.

A River Below

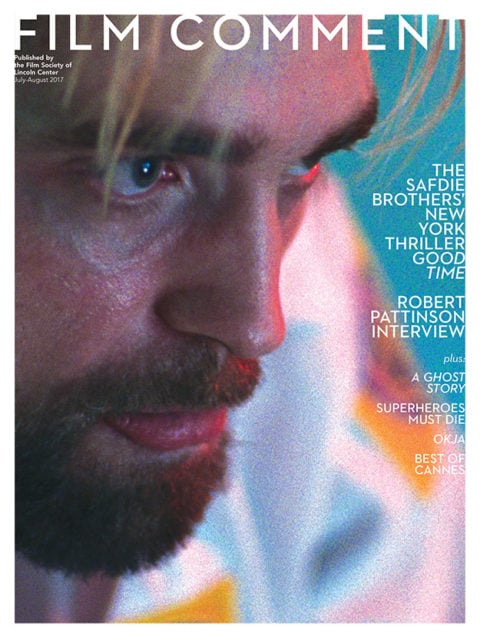

It is a relationship that always fascinates, providing a buzzing subtext to what’s on screen and serving as an abiding source of curiosity for audiences. (“How did you find your subject?” “What was it like to have your life made into a movie?”) Yet sometimes the relationship is more than just the backstory. In Laura Poitras’s Risk, it rises from undercurrent to main current. Though it began as (and to a large degree still remains) a piece of embedded reportage chronicling the work of WikiLeaks, Risk wound up focusing more on the director’s uneasy relationship with lightning-rod founder Julian Assange. That’s not just a behind-the-scenes tale—it’s a traceable development based on changes made to the film between public presentations in 2016 and 2017.

The version of the film that screened at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival reflected the director’s measured but sympathetic view of the organization, its mission, and its leader. It was a group portrait in which Assange—his ideological crusade as well as his personal embattlement—is featured prominently at the center, with the director choosing to stay completely out of the picture. But as Poitras told the Los Angeles Times and other outlets at the time of release, Assange’s verbal assault on her around its Cannes premiere (along with, one presumes, a cascade of bombshell developments regarding WikiLeaks) caused her to revisit the material and interrogate her own feelings and observations about him. When the film finally opened theatrically this spring, it included new material captured over a momentous year for the organization, a more extensive consideration of sexual abuse allegations against both Assange and collaborator Jacob Appelbaum, and a Poitras voiceover cribbed from her production journal.

Her words speak to a general sense of unease around Assange, and also serve as a fascinating and, frankly, brave self-interrogation. The post-Cannes addition of a director’s reflective voiceover invites the viewer to reflect upon her reportage in turn: had she gotten too close to the flame to view Assange and his team objectively, with objectivity only becoming possible after she felt burned by him (or after they felt burned by each other)? Another filmmaker might have kept herself out of the fray, or sought to appease Assange enough to peaceably release the movie, but Poitras instead dove headlong into the conflicts and complications. She allows viewers to question what they’re seeing, and why they’re able to see it. In her voiceover diary, she wonders why Assange lets her film him, but his reaction at Cannes gives a clue. It wasn’t just any filmmaker he allowed to listen in on strategy sessions with his attorneys, or follow him into exile; Poitras was on his side, and he trusted—and also sought to leverage—her accordingly. Just because she ultimately wasn’t, and he ultimately shouldn’t have, doesn’t mean she (or the film) didn’t benefit from his trust, or from the slippage between her presence as filmmaker and fellow traveler. We lionize and crave intimacy in documentaries, but how is that intimacy achieved, and what are the costs of that intimacy for both the subject and the filmmaker? In Risk, Poitras lets us weigh those costs while she does the same.

Risk

“You’re fulfilling for that person a very basic need that we all have, the need to be recorded exactly for what we are,” Albert Maysles told author Liz Stubbs in 2001. “So in a way you’re doing a service of giving that person not a biography, but an autobiography.” The rub is that it’s an autobiography authored by another, presenting an irreconcilable tension between what the filmmaker owes a subject, and what a subject feels owed by the filmmaker (who’s there to record, but also to make). Not every dance leads to where these two films did, or where Nina Davenport’s queasy landmark Operation Filmmaker (2007) wound up, with a subject feeling entitled to a career, asylum, money, and more from the production. It’s a tension that’s often reconciled, if precariously, in the edit, hinted at but largely kept off-screen. But what subject doesn’t feel as Rasmussen does when he says, “I completely gave myself”? We may know that “completely” is a bit of a stretch, particularly from someone so camera- and career-savvy—and he’s got nothing on Assange in that department. But the key word is “gave,” and the unspoken one, the one toward which the finger points and the abuse is hurled, is “took.”

Even in the best possible circumstance, it can’t really be otherwise. The participants will always be unequal, though they can operate symbiotically. Maysles himself was a master at this, establishing trust and fostering candor without letting us forget that he and his probing camera were also in the room (or on the train, per his latest and final film, In Transit). Yes, to be a documentary filmmaker is to be some glorious mix of artist, journalist, psychologist, and empath. But to be a documentary filmmaker is also to be a vampire. And an enabler. And a dupe. At minimum, it requires risking being all of these things. Filmmakers like Poitras and Grieco go one further, risking our seeing these roles baldly in play, allowing us to scrutinize the person behind as well as in front of the camera, and inviting us to witness an already fraught relationship bowing from the strain.

Eric Hynes is a journalist and critic, and associate film curator at Museum of the Moving Image in New York.