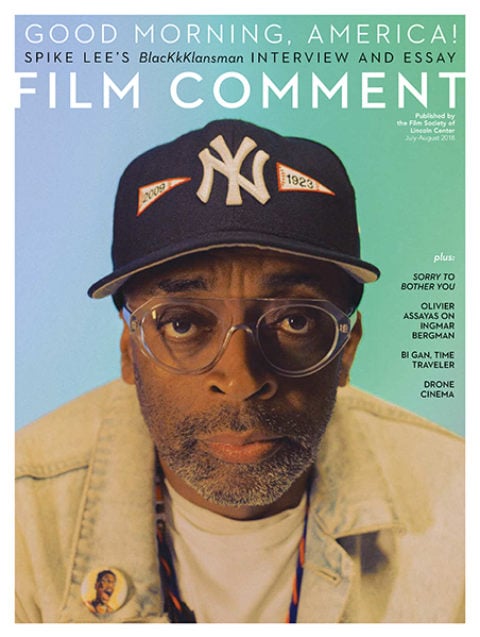

By Amy Taubin in the July-August 2018 Issue

Law of the Land

In Ash Is Purest White, opening this Friday, Jia Zhangke charts how one woman survives and thrives on the criminal margins

From the July-August 2018 Issue

Also in this issue

The following is an extended version of what appears in the July/August issue.

Jia Zhangke’s Ash Is Purest White opens and closes in the world of Chinese small-town gangsters, the world of jianghu. The film’s Chinese title, Jiang Hu Er Nv, can be translated as Sons and Daughters of Jianghu, and Jia acknowledges the influence of the Hong Kong Triad films of John Woo and Johnny To in one brilliantly staged gang warfare scene (the turning point of the narrative). Yet Ash Is Purest White seems to me rooted in a very different genre, that of the women’s picture, transformed for the 21st century into a narrative of a woman, Qiao (Zhao Tao), who begins as a gangster’s moll, is soon betrayed, but finds her independence by staying true to the code of underworld even as the mainstreaming of China continues apace into the second decade of the century. Qiao’s journey parallels the development of 21st-century China but stands in opposition to its unquestioned patriarchy.

It is a great role for Zhao Tao, who has taken the central female role in most of Jia’s films, most memorably in Unknown Pleasures (2002), The World (2004), Still Life (2006), and A Touch of Sin (2013). In Ash Is Purest White, she has the opportunity to deploy the full expressive range of her emotional and physical powers. The other amazing aspect of the film is that Jia gives us a history of image capture in his films. Working for the first time with cinematographer Eric Gautier, he goes from DV to Digibeta to HD video to 35mm to the high-end Red camera, and yet the changes in the image are never notable for themselves but become the means to show the transformation of his filmmaking and of China itself.

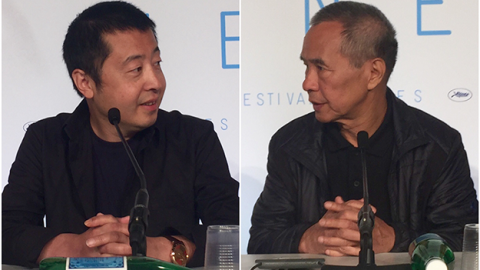

I spoke with Jia and Zhao separately at the Cannes Film Festival in May during a hectic press day. Ash Is Purest White will be distributed in the U.S. by Cohen Media Group.

Jia Zhangke

Because Ash Is Purest White is a melodrama centered on a female character, I wondered if it was influenced by the 1940s Hollywood “women’s picture” genre.

Jia Zhangke: No, I think the film was influenced mainly by the Hong Kong Triad films of the 1980s and ’90s—John Woo and Johnnie To. What I wanted to express is jianghu as an integral part of Chinese culture. The gangsters are people living on the margins and they organize themselves in order to survive. They have their own rules and value system. You could think of it as a counterculture standing against the mainstream. I used jianghu as a vehicle to examine the accelerated mainstreaming of Chinese society, especially in the past 10 years. And since I am a male director and China is very much a male-dominated society, I needed a female character to challenge the male-centric mainstream society. So you have these two elements that challenge the mainstream: jianghu culture and a female character who is the focus of the film.

Does gangster society act, in part, as a metaphor for independent filmmaking?

JZ: Yes, exactly. Independent filmmakers are analogous to people in jianghu culture. As an independent filmmaker, I take a risk in challenging the existing film order and the censorship laws. People joke that my role in independent filmmaking is almost like that of an assassin.

Does the film have a release date in China?

JZ: We are aiming for between June and August. We want this to happen quickly because we don’t want to leave time for complications to arise.

Did you enjoy working with the largest budget you’ve ever had?

JZ: It is the largest budget I’ve ever worked with, but compared to other films made in China, it is on the medium-low end. I had a lot of creative freedom because the investors support my style and my way of making films.

What is the relationship between this film and Still Life? I’m thinking in particular about the strange sighting of the UFO in both films.

JZ: This film has a lot to do with Still Life, which was made in 2006, but also with Unknown Pleasures, which I made in 2002. The female character in both films is played by Zhao Tao, who plays the central character in this film. I wanted to construct a narrative for this new film that would tie these films and the characters she plays together. You can see that she was very much the same person in all three films. In the first part of this new film, her character has similarities to the young woman she played in Unknown Pleasures, and in the second part, when she gets out of prison, she is similar to the character she played in Still Life. She is traversing China and the first 18 years of this century, which is a time of dynamic change. I think her constant motion is what I’m trying to capture. During this expanse of time, she has to toughen herself up in order to make it. And what the UFO sightings remind us of is how small and insignificant human beings are. But all the wandering around that she does allows her to expand her perspective and become an independent person who can take care of herself.

Toward the end of the film when Qiao tells Mr. Bin [Liao Fan], her former lover, that she no longer has feelings for him, does she really mean what she says or is it a way of defending herself from his rejection?

JZ: When I discussed this scene with Zhao Tao, we considered making it ambiguous, but we decided to go back to the concept of “ash”—that although the burning feeling of love is dead, there is still a residue of warmth on some level.

So at the end of the film, is her feeling of disappointment not only because he has been disloyal to the values of jianghu but also, on a personal level, disloyal to her?

JZ: I think she eventually turns to herself to be self-sufficient, to count on and believe only in herself as an individual. She doesn’t want be part of the mainstream structure of marriage and that kind of love. She wants to find her own way out of this.

Zhao Tao

I asked Director Jia this question, but I also want to ask you: toward the end of the film, when Qiao tells her former lover that she no longer has feelings for him, is that true or is she defending herself from being rejected by him again?

Zhao Tao: When I started thinking about how to play the character of Qiao, I thought of her life in two stages. In the first, she is involved with Mr. Bin and as a result, she goes to prison for five years. The second stage begins when they break up. His betrayal completely destroys the world of love for her. So at the end when she tells him that love is gone but she still has a sense of responsibility to him and a moral duty to take care of him, I think it’s very much to maintain her own dignity and to show him that she holds these jianghu values of responsibility and loyalty—Qiao is letting him know that this is something that I will continue to do for you, but when you broke up with me, you destroyed the kind of relationship we first had. What we talked about a lot for the character was this sense of duty, responsibility, righteousness, and moral stature. And this is part of her sense of what it means to be human. But when he tries to take her hand when they are sitting in the car, she refuses to go along. She is letting him know that she has this sense of duty but that shouldn’t be confused with the kind of love she felt for him when she was young. To be a woman within jianghu, a society that is so male-centric, she has to protect her dignity.

What was so interesting to me was that by the end of the film, all the male characters have given up on the values of jianghu and it’s only the female character that stays true to them. And that was never the case in the Triad films. The jianghu values were never represented in a female character. So you have a female character that is carrying on a tradition of the underground, which challenges the mainstream. It’s a great role.

ZT: I enjoyed playing it so much.

After Director Jia gave you the script, how much input did you have in the specifics of the character and her trajectory?

ZT: The exchange and discussion we have about the character is always grounded in the script. His screenplays are very precise and there is nothing extraneous in them. So the script is my inspiration when I build the character. Of course, there is a traditional way of working with a director who is also the screenwriter, which is through reading and analyzing the characters and the plotlines, and then the director will offer his perspective on all this, and after that, I begin to translate all of these ideas into things I can do to create the character.

Director Jia spoke about the characters you played in Unknown Pleasures and Still Life as being aspects of a single person, and that they were also somehow part of the character you play here. Did you think about picking up those characters and taking them along on the journey of the character in this film?

ZT: When the director first talked about this concept, I was so excited because I had never seen a film that was self-referential in this way. These characters were all completely different people, so for me to come up with a way so that viewer could connect them was so new and challenging for me to do. Having said that, the character in this film is completely new. She has very little to do with the previous ones. When I designed the character of Qiao, I mapped out her life from the moment she was born in this small town, to elementary school, to middle school, all the way to 2018, so I have the timeline in front of me. And then I started to think about how I could incorporate the 2002 and 2006 characters and still come up with a completely new character with a unique way of thinking and expressing herself.

And yet, there was one moment, after she has gotten out of prison and she’s walking by herself in the town that is the main location of Still Life, that I wondered if Jia had incorporated footage from the earlier film, because you looked so much like you had looked in 2006. And of course, the year, in terms of the chronology of Ash Is Purest White, is also 2006. It’s as if the ghosts of the past are haunting the film in that particular town, which has, in part, become a ghost of itself because of the building of the Three Gorges Dam.

ZT: Yes, it’s the moment when all her money has been stolen and she’s trying to find a way to continue her life into the future.

Amy Taubin is a contributing editor to Film Comment and Artforum.