By Jordan Cronk in the January-February 2020 Issue

House of the Spirits

Pedro Costa returns with the masterful Vitalina Varela—a story of mourning and rebirth, a return to old haunts, and quite possibly the most beautiful film of 2020

Early in Pedro Costa’s 2014 film Horse Money, a Cape Verdean woman named Vitalina recounts in detail the heartrending story of her late arrival to her estranged husband’s funeral in Lisbon. It’s an unforgettable moment in a film that, while centered primarily on Costa’s frequent lead Ventura, announced an unexpectedly vital new figure in the Portuguese director’s work. Indeed, five years on, it’s Vitalina’s presence and performance that linger most in the mind. Costa’s new feature, Vitalina Varela, returns to this story, dramatizing Vitalina’s arrival in an impoverished Lisbon neighborhood and her painful process of reconciling the memory of her husband with the man she learns led a duplicitous life in her absence.

From the January-February 2020 Issue

Also in this issue

Since inaugurating a radical form of collaborative nonfiction with In Vanda’s Room (2000) and Colossal Youth (2006), Costa has been developing this approach into a new kind of dramatic portraiture, with Ventura and now Vitalina as his primary creative partners and subjects. Still guided by the spirit of the old Hollywood and modernist masters (John Ford, Jacques Tourneur, Jean-Marie Straub) that so indelibly marked his early colonial allegories O Sangue (1989) and Casa de Lava (1994), Costa has become a touchstone for an entire movement of contemporary art cinema ranging from documentary to the avant-garde. He now enters a new chapter in his influence and profile with Vitalina Varela’s selection by the Sundance Film Festival. But while his hands-on commiseration with Portugal’s downtrodden and dispossessed, as well as his impossibly rich compositional sense, have and will continue to be emulated, his humanism and unwavering dedication to his craft—both pushed to bracing extremes in his latest—have yet to be matched.

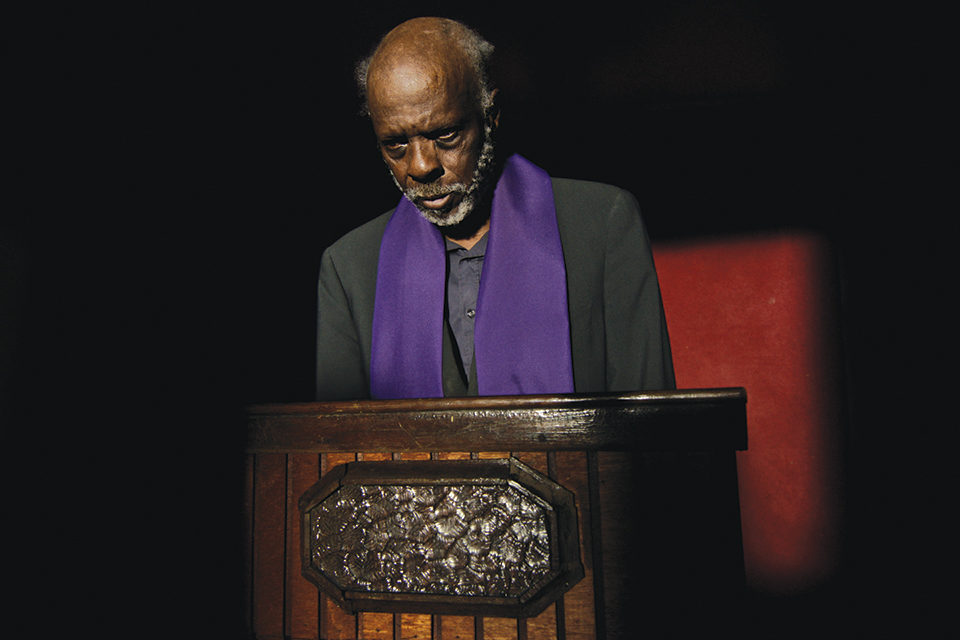

At once Costa’s saddest and most spiritual film, Vitalina Varela employs gradually interlocking story threads to follow both Vitalina as she settles her husband’s affairs and endures the condemnation of his friends and associates, and the plight of a fragile, guilt-ridden priest (played by Ventura), whose vacant church becomes a sanctuary of sorts for these damaged souls. Shot with customary rigor and an increasingly refined and unparalleled sense of space, light, and shadow, the film invests a tragic episode in its heroine’s life with an intimacy and grace that forges new dimensions in Costa’s cinema. Just days before it won the Golden Leopard last summer in Locarno, where Vitalina also picked up the Best Actress prize, Costa and I spoke about the film, subsequently supplementing our conversation over email.

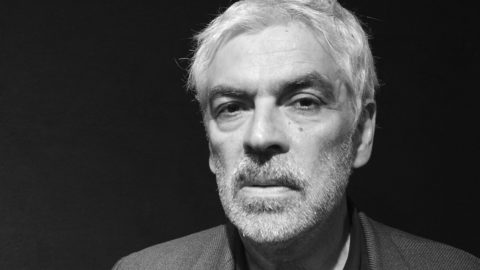

Pedro Costa with Vitalina Varela and Ventura on the set of Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, 2020). Photo by Vítor Carvalho/Courtesy of Optec Films

Let’s start with the house Vitalina returns to in Lisbon. It feels haunted to me, and not only by Vitalina’s husband.

One of the starting points for the film was locating a house in that neighborhood. One day in the middle of the shooting of Horse Money, I was trying to find an interior of a house in the African neighborhood of Cova da Moura, in the suburbs of Lisbon. I was looking for one of those houses that I remembered from the old Fontainhas district where I shot In Vanda’s Room. I wanted to do some portraits of people in their own homes for a musical sequence with the song “Alto Cutelo.” I asked for help from a friend who lives there, who said, “I think I know a house that you might like, a very traditional and simple house. The problem is that the guy who used to live there died, and the house is now closed and empty. But let’s try—perhaps we can go through the back.” And when we were approaching the house and while he was telling me this, we saw the door open and Vitalina appeared in the doorstep, all dressed in black, an extraordinary, grieving face. This alone deserved a film. She was fearful; I imagined she thought: “Who are these people? Police? Immigration office?”

But you’re quite right, it’s not Vitalina’s husband haunting the house, it’s Vitalina haunting it herself. Her fury makes those walls tremble and the roof collapse.

This was five or six years ago?

This was 2013. When we met I explained what I was doing. I don’t know if she understood it completely when I babbled things about “shooting a film.” But when we left I wanted to know more about her. No one knew exactly who she was. I even felt a bit of hostility in the air; no one wanted her there. I went back a week later and she let me shoot in the house, and I asked her if I could take a picture of her; she agreed and she ended up in the film. Ventura came with me, and when they started talking they discovered that they were related, like distant cousins. That made it more comfortable for her. When she played her part in Horse Money, where she tells the story of her arrival in Lisbon, I had the immediate feeling that she could go much further, and she wanted to, even if only to occupy herself. She was not afraid of this work; she gave it her all, body and soul. So after Horse Money I went back and stayed with her for weeks. We sat in her room and she began telling me her story right from the beginning: her childhood in the mountains of her island, her first love Joaquim, their marriage, his escape to work in Portugal, his silence, his death, her grief.

There are a number of people in the film besides Vitalina—non-actors, locals from the neighborhood. At what point do you feel comfortable and confident enough to ask them to be in your film, and how does that conversation evolve?

With Vitalina it took a long time—not to convince her, but to convince me. To make sure that such a film was possible: how to do it, how to organize it, how to structure it. Because in the beginning I thought that this film could be a little bit wider, a bit more open, and that perhaps there could be something shot back home, from when she was younger, that happy part of her life—something sunny, in the open air. But I think she wanted to stay in this moment, this moment of mourning. She was going through the worst, most painful moment of her life and I was proposing for her to organize, to work out and reveal these terrible feelings and emotions, to turn all of it into a film. And the more I heard her plaint, the more afraid I was. I told her: “Vitalina, your words, your pain will be in the film for all to see. They will be the film—aren’t you afraid?” And she kept saying: “You must!” I think we both wanted to exhume this horror, and the film would be the mourning.

I decided we would lock ourselves up in this small, dark house and do the work. So it took a while to convince me that maybe we could do it, that she could perhaps go through this ordeal, and I could perhaps film it. This was a bit more difficult than the other films—not because she wasn’t getting there, or not wanting to work, but because of me. How can I explain . . . Even if I insist that everything is true and real, this story is still less fantastical. There’s less fantasy if you compare it with Horse Money. It has a different kind of pain or suffering. Just the fact that it belongs to or comes from a woman gives it a certain gravity that Ventura—or perhaps men—cannot carry.

Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, 2020)

Is there a certain comfort for Vitalina in being in the neighborhood, and also in the fact that you’re now much closer than while making Horse Money?

Yeah, I really think the time spent doing this film helped her a little. All the films need particular preparation in the sense that we not only need to become friends but also some sort of trust has to be there. I guess our crew understood—we’re only four or five, so you can become close quite quickly. Her mourning was the shooting, and vice versa. Sometimes, because of cinema, I find myself living more with the dead than with the living. In this business we’re always invoking and calling the other side…

Vitalina already had the experience of Horse Money, but it was very short compared to this one. And shooting in her house, in the very center of the neighborhood, I’m sure that gave her a sort of compensation, almost a revenge. She didn’t seem embarrassed, she wasn’t hiding anything from anyone anymore. When she arrived, everybody was suspicious: “Why do you want to stay? What do you expect to find? Go home, your husband is dead and buried, your life isn’t here. Don’t you know he had other women? Don’t you know he was a shady guy? He forgot you!” Every kind of injury or insult.

I’m doing films among a very disoriented community: once they were peasants, then they were immigrants and they were brutally exploited. I’m working in the middle of confusion, and it’s risky. My job as a filmmaker is also to not betray the trust they offer me, their life secrets, their dignity, their intimacy. It might sound absurd since we’re dealing with cinema, but my main concern is to keep their intimacy intimate. Anyway, we’ll grow old filming together, and it’s right there for everyone to see. It’s a kind of archive now, a memory album.

On the topic of an archive, the element of time in your work has grown especially pertinent in recent years.

Yes, some of the people you see in this film, even in the very first shot, are already gone.

All of your neighborhoods seem haunted by something.

[Long pause] Death… These people were condemned. And long before they were born.

Tell me about Vitalina’s entrance. Actually, about her entrance and one of the last images of her in the house: in both cases she’s barefoot.

In Horse Money she tells the story of how when she came to Lisbon on the plane she was stressed and couldn’t pee. When we talked, she said, “I was completely numb. I didn’t know where I was. I had this lady helping me, and she undressed me.” I said, “Were you naked on the plane?” She said, “I was in my nightgown, sitting for the journey, because I was so hot, my body was burning, and my feet were so swollen I couldn’t walk.” I remember thinking that we needed to film this woman on fire, coming to her husband’s tomb to avenge herself. And then, as she is always saying: “The only moments I can forget all my sufferings is when I’m working the land, a hoe in my hands, bare feet. I’m happy there.” No Cape Verdean or African works the land with shoes or sandals. So stepping on this new world for the first time with her bare, wet feet should rhyme with her leaving her pain behind—that was important. Almost everything comes from associations. Little bits and pieces come together from her stories, her memories, and I try to organize things and connect them in a way that’s interesting.

When first visiting these neighborhoods are you mentally mapping how you’ll visualize the space in the film?

I try to know those alleys and those houses the best I can. I now have time—a filmmaker should have all the time to wander around the spaces he’s going to film and should have the freedom to make them his own. I try to live them, to feel and recognize them because of how the light affects those spaces, of how the light caresses the walls at 11 in the morning or at six in the evening. And then it’s an effort of concentration in every sense. But it’s no different than other aspects of our work—text, performance, sound, light. It’s not a minimalistic thing—it’s concentration. But of course, concentration means a little bit less—organizing the parts and the elements in a more essential way. With a bit of luck, everything will come together at the same time.

Let’s talk about the colors. Red is a prominent color in the film—the blood on the bed being the most obvious example. But the different shades of blue struck me most.

I vividly recall one morning, three-quarters into the shooting, I arrived at Vitalina’s house quite early, and she was dressed in this blue robe, the robe that she wears in the film. A very beautiful ultramarine blue, a very deep blue. And I asked her, “What’s new?” And she said, “I just thought I would go work a little bit.” She has a little garden, not far from the house, and she likes to go there and grow her vegetables. “It’s not that I’m forgetting. It’s to work.” I’ll never forget that “not that I’m forgetting.” I felt something was beginning to go away. So she can wear something brightly colored if she’s working. It means she’s happy, and that she can forget for the moment. She told me these are the only moments when she’s happy. And she means really happy, not having to think about her husband or loneliness. Sometimes she says, “As you like to do your films, I like to work the land.” So we used the robe in the film—we even have a shot where there’s just a little bit of sunlight on her shoulder, and it’s very blue.

I’ll always prefer the neighborhood as it is. I’ve never hidden the fact that one of the thousand reasons that attracted me to Fontainhas and that made me want to work there was an aesthetic one. In this film, Vitalina’s door is also blue. They’re very fond of primary, bright colors. They like to paint their houses blue and yellow, green and red. And life leaves its marks on the paint; it draws and remembers. But life also made them a little bit tired and oblivious, and the colors fade. But I can’t blame them. They are oppressed. Now it’s the social-democrat council governments that tend to paint the houses as part of their social assistance—yellow, because they will be happy! They hate it. Their houses were made by their own hands, brick by brick. And even if the walls were a bit crooked, they loved them.

Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, 2020)

How was Ventura doing during the shoot? I know he was sick during Horse Money.

One of the reasons shooting this film was so long and difficult was because of Ventura’s health. This was a difficult project for Vitalina. It affected us all, but it was especially difficult for Ventura. During the shooting, he suffered two heart attacks. The first happened while we were rehearsing. But it was just a scare and it was forgotten quite quickly. The second one hospitalized him for a month. He had to do physiotherapy for quite some time. Ventura got quite scared. Having one of us in the hospital changes everything—at least in our kind of work. So that was the moment I said, “Wait, let’s think about this.” This kind of thing, and the things we are telling in the text of the film: everything seems to be making some strange sense—an almost diabolical sense.

So we adapted ourselves to shoot most of Ventura’s scenes in this huge abandoned cinema that we found in the suburbs and adapted into our own film studio. We tried to make it a bit soundproof so that we could record direct sound. We had heaters and everything to make Ventura as comfortable as possible. It’s not the first time I’ve made this provision: Ventura, Vitalina, Vanda, all of them belong to a certain tradition and lineage—they are studio actors. You could even say they’re the last ones. They need a certain protection and enclosure and a certain light upon them. But fortunately for Ventura, nothing was seriously damaged. He trembles, but nothing was affected. He walks fine. He even joked, “If I was feeling 100 percent I’d be a better priest.”

How has your collaboration with him changed over the years?

We’ve been growing old filming together. Reaching our limits together. It’s comforting.

Regarding his work in this film, as we were discussing the project I mentioned to him that his character would be a priest, and he said, “Whoa, whoa, whoa. I don’t like priests.” He hates priests! I told him this would be a different kind of priest. And actually this priest exists. One day, Vitalina told me a true story that happened to this young priest from Cape Verde who did not want to baptize a group of people for some bureaucratic reasons; he told them they were not prepared to be baptized and that they should go to another parish. So they all leave in a van, the van crashes, and everybody dies. He lost his mind and began to lose his faith. The guilt-ridden priest becomes a beggar in the streets of Cape Verde and the bishops decide to “deport” the poor priest to Portugal, where, it seems, he still survives in extreme poverty. So we said, well, maybe he’s settled in this church, and tried to congregate but nobody comes, so he’s here sad and all alone—a kind of fool on the hill.

Ventura really liked that idea: having his own church, even if he knew he would have no congregation. Not only did Vitalina witness the accident—which she recalls in a scene in the church—but Ventura’s eyes twinkled with malice when I proposed to him this scenario. That was it! We built the set for that church ourselves; we copied the real shack church that we shot when Ventura enters at night. It sort of reminds us of the caves of the primitive Christians. Vitalina adored that church. She sat in those chairs rehearsing, praying, thinking.

The shot on top of the house when it’s raining and Vitalina is fixing the roof seems to me perhaps the closest you’ve come to John Ford.

That’s because of Vitalina’s hand over her eyes, isn’t it? It was a difficult shot to prepare. It involved some construction in our improvised studio: the wind, etc. But the actual shooting was easier than we all thought it would be; we didn’t need that many takes. It was just because Vitalina had really performed those actions quite a few times in her real life: climbing to the roof on stormy nights, trying to stop the rain from falling in her kitchen or on her bed. Some days we also felt it, the fury of the wind on the tiles, the rumble of the dirt on the roof. I can tell you it was quite scary! But it never discouraged Vitalina. She had to go up and try to repair “that awful job Joaquim had done.” Vitalina and I just agreed on a certain number of actions and steps and pace for the roof scene.

Thinking that it would be a rough shoot, I also anticipated that it could be somewhat documentary. So I didn’t block the ending; I just told Vitalina to go as far as she could, and then we would cut. And as we went along, I saw that she slowly came to this posture, her hand over her front, eyes far out on the horizon. I never asked her why she did that or what was she seeing. But it was because of this shot that I decided to go to Cape Verde to shoot the ending of the film. Who knows, maybe Vitalina is seeing herself, on top of another roof, across the ocean.

But for me, with this scene you could also think of some of the women in Mizoguchi’s films, if only because John Ford was more manly. But it could also be Russian—it could be Dovzhenko. But of course if you have that, what can you do: you’re surrounded by ghosts again. I’m not saying it’s a shot or an image I remember from Mizoguchi. It’s more a spirit of mothers, widows, running around the landscape in Japan, escaping soldiers, battling, searching for food, repairing, et cetera. But, I guess, more than Ford or Mizoguchi, I’m thinking of a filmmaker who was certainly important for this film: Mikio Naruse.

The first time I went to Japan, I met the great Japanese writer, essayist, and critic Shigehiko Hasumi, who wrote the most beautiful book on Ozu. I had seen a lot of Ozu and Mizoguchi, but it was Professor Hasumi who first told me about Naruse. This must have been almost 20 years ago, and I remember him commenting: “Mikio Naruse was a very shy, reserved, and tormented man. Because he had the feeling that the world had betrayed him.” I remember Hasumi gave me some VHS tapes: When a Woman Ascends the Stairs, Mother, et cetera. He made hundreds of films, all of them absolutely marvelous. There’s a kind of sordid evocation of the couple in his work—and by evocation I mean some inserts or some ways of suggesting the sordid bits of a relationship that are very strong.

Vitalina Varela (Pedro Costa, 2020)

It’s interesting that you would mention both Mizoguchi and Naruse, because they’re both recognized as women’s directors, and Vitalina is your first female lead since Vanda.

This film does come closer to In Vanda’s Room in a lot of ways, I think, in trying to surround Vitalina with the sound of a place that she didn’t know. She didn’t know the neighborhood that I knew. She’s new here. So all she hears in the film is new to her. The sound that was in Vanda, the brouhaha of life, and the contradiction of public and private—there’s nothing secret, and at the same time nothing is public. The frontier between shame and spectacle is very thin. And that’s very interesting. You can work with that, and we did in this film. Vitalina’s surrounded by sounds, by this life… or death, I don’t know. But this idea for the sound comes straight from Vanda, from the old neighborhood—the streets, the houses, the windows, the stairs. I think with this film I was trying to get back home in a sense, to my film home, and Vitalina is new in this home. She comes from the mountains, she comes from the sunlight. She’s not used to being imprisoned in a cell.

In a way, I was relieved when Vitalina suddenly appeared in my life. I was spending most of my time with Ventura, Nhurro, and the “boys,” in a man’s world. As I said, this encounter with Vitalina deserved a film. And I also felt it could give me the chance to approach the Cape Verdean immigration from the woman’s point of view. The history of the African diaspora is generally a men’s tale: they sail first and come to the new world, leaving their women behind, and sometimes their children too. “I will save money; I will send you a plane ticket in a year or two.” Needless to say, after a few months most men forget. Life in the big western cities is hard, they work long hours, it’s impossible to put money aside, build a shack… And then there are the pleasures and traps of capitalism. They forget to write; they forget to call. Until they meet another woman and they find themselves with two families: one in the new world and one waiting back home on the islands. It’s a sad sociological cliché. There’s a line in Sans soleil where Marker draws a portrait of the Cape Verdean people: “How long have they been there waiting for the boat? . . . A people of nothing, a people of emptiness, a vertical people.” In reality, it’s the Cape Verdean women he’s depicting.

How does Vitalina feel about traveling to festivals with the film?

It’s the first time she’s traveled outside of Cape Verde or Portugal. Last night, after the screening, she told us that she would like to keep watching the film, that she wished the night could keep going with her on the screen, and that she would like to sleep in the theater. Something she still finds strange is the fact that the film has her name. I asked her, “Don’t you like it?” She said, “No, no, it’s just strange. I could have given you a good title.” [Laughs]

You said at the time of Horse Money that you made that film to forget, and that you hoped the next film would be a good thing. Is it a good thing?

I think so, yeah. Even if you think it’s very sad—and maybe it is—it’s a good thing. A good thing in the sense that we tried our best within our capacities. I think this film is a very moving effort to say goodbye to a loved one. Vitalina is saying goodbye in order to heal the wounds and appease her sufferings. She has to go on living and remembering her late husband’s betrayal. A little altar with a crucifix, two candles, a few photos of him, and a saucer to collect some change… we lost the will to do these small things, didn’t we? In the Cape Verdean community, mourning still has a certain importance. Vitalina couldn’t attend the wake and the funeral because she arrived too late, everything had already been taken care of. But since in real life she didn’t have the chance to take part in the ceremonies, she could live the whole ritual in this film. I guess that Vitalina somehow wanted to claim her spousal right to perform these funerary rites.

And in the end, it’s our turn to say goodbye to Vitalina. Every film must learn to say goodbye to its characters. After all that Vitalina endured, it would have been too easy to condemn her to the purgatory of those four walls. She must have her justice. She goes back to the very beginning, to the highest mountains, to the beginning of her love story with Joaquim, to the sparkle of love and happiness. Vitalina gave her heart and soul to this film. So in that sense, it is good work. Not better or worse than other work. But it’s good work, useful work. In the end, we rejoin something I believe that cinema must go on doing: keeping the flame alive.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is a member of the Los Angeles Film Critics Association.