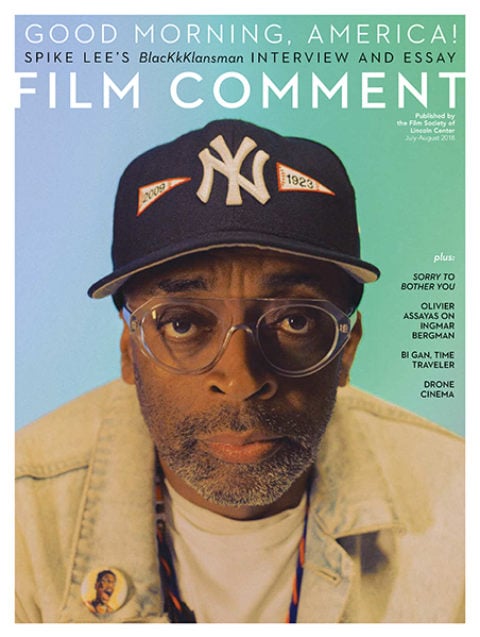

By Kent Jones in the July-August 2018 Issue

Festivals: Drifting Apart

Cannes risks the loss of cherished ideals, though filmmakers fight the good fight

For the last 19 years of my life, I’ve traveled to the Cannes International Festival of Film, in one capacity or another. Every year, when I come home, I’m asked about the festival and how it was, and I confess that I never really know what to say. In the reports published annually in this magazine, various writers including myself have attempted to enumerate and describe the inconveniences and annoyances and humiliations, small and large, that are simply part of the Cannes “experience,” in addition to the festival’s general atmosphere of listlessness, and exhaustion. “Oh, I feel so sorry for you…” people say in response. “Did they make you go to the south of France to watch movies? Sounds terrible…”

From the July-August 2018 Issue

Also in this issue

Of course it’s unseemly to complain about going to the Riviera to watch new movies by some of the world’s greatest filmmakers (never mind that we could just as well be watching them in a mall in Bismarck, North Dakota). But the usual frustrations aside, there is now something a little sad about Cannes. A local restaurateur told my friends and me that his festival business is down 40 percent from what it was in 2012, a shocking statistic. The festival has felt less and less populated over the past few years and there is a growing air of desperation in all of the ceremonies and the protocols and shows of formality. In a way, it feels like the Cannes Film Festival, the film business, and the art of cinema have drifted away from each other like tectonic plates, each becoming its own separate territory.

Just before this year’s festival began, a man named Pierre Rissient died at the age of 81. A few hours after his death, I went to a screening in Paris of a film that was not invited to Cannes but should have been, and Pierre was supposed to have been there. His death was not unexpected—he had been ill for quite a while—but it came as a shock nonetheless.

Pierre Rissient. Photo: Jerry Schatzberg

I think that most readers of this magazine know Pierre by name. For those that don’t, he was not easily classifiable. In his youth, he was a programmer at the Cinéma Mac Mahon in Paris and Godard’s AD on Breathless, and in the ’60s he and his lifelong friend Bertrand Tavernier went into partner-ship as publicists. Pierre directed two little-seen films, one of which, Cinq et la peau (1982), was shown in Cannes Classics this year, but he will be remembered not as a filmmaker but as a man who loved the cinema so passionately that he traveled the world to see and discover films and share them with as many people as possible. In other words, Pierre embodied cinephilia and the appreciation of cinema in the best sense. My last communication from him came on April 29, one week before his death. He wrote to me privately to tell me how excited he was to see my film, which I brought with me to Paris to show him—I wish I’d had the chance. And, as usual, he had a new film to champion—Lee Chang-dong’s Burning.

The screening of the restoration of Cinq et la peau became an impromptu memorial, at which Pierre’s old friends Bertrand and Thierry Frémaux stood side by side on the stage of the Salle Buñuel. At one point, as Thierry described Pierre’s role in Cannes (where he was a kind of permanent ad hoc advisor) and in the world of cinema in general, he spoke the words, “Il nous a protégés” (“He protected us”). And then he broke down.

Many filmmakers I know felt protected by Pierre—to name a few, Claire Denis, Olivier Assayas, Hong Sang-soo, Jane Campion, Jerry Schatzberg, Clint Eastwood… and Lee Chang-dong. And further back in time, Edward Yang, King Hu, Abbas Kiarostami, Lester James Peries, John Berry, Lino Brocka, and many, many others. The same goes for countless critics and programmers. Pierre could be unreasonable, imperious, and perverse—I’m thinking of the time he sat outside a screening in order to buttonhole those in attendance on their way out (one of his favorite tactics) and announce that the movie we had just seen was “proof that Vertigo is a bad film.” None of that mattered, though. What did matter was his abiding love for the cinema. Is it meaningful? Does it contribute to the cultural conversation? Does it promote a positive image of this or that interest group or create a platform for that or this burning issue? False questions for Pierre, for whom the only question was: is it cinema? Pierre protected us by standing tall for the cinema amid the winds of so much fashion and moralizing. Like Flannery O’Connor, he scoffed at the notion that art is obliged to justify itself as a delivery system of moral ideas—like O’Connor, he knew that art was, in and of itself, a “good.”

I think that right now, Cannes needs protection. It is caught in the gears of historical change, and Netflix is just one among a multitude of problems that has beset it. The ground is shifting rapidly in the world of film exhibition, so rapidly that what was true five months ago is no longer true today. For many companies with new business models, flying over a horde of actors and publicists and executives and putting them up in villas and hotels in order to get seven minutes of photo opportunities on the red carpet seems beside the point. The press now starts dwindling off after the first few days, for reasons that I don’t entirely understand. And the selections of films betray a spirit of calculation, a brain-twisting effort to strike an increasingly difficult balance between getting stars on the carpet, representing the world at large (at a time when filmmaking itself has been diminished to a trickle across vast swathes of the planet), avoiding the appearance of favoritism toward this or that filmmaker, and so on. This year was supposedly the year of the woman in Cannes, but the gestures were odd. The pledge to show more films by women, for instance, was overshadowed for many people by last year’s sad decision to reject Lucrecia Martel’s Zama outright.

Nonetheless, amid all the calculation, there were more good films this year than last year. Some, like Godard’s Le Livre d’image, were predictably good. From Notre musique on, Godard has been making last films and video works, and it’s been fascinating to watch him try to arrive at some kind of endpoint where the film itself, his ongoing work, his relation to the art of cinema, and the impending end of his own existence will somehow converge. One might say that this quest began with the final moment of Histoire(s) du cinéma and his recitation of Borges’s text about Coleridge’s flower, but in that instance the gesture felt premature, an expression proper to a final moment that had not yet arrived. Godard is now 87 years old, and his voice is noticeably weak and trembling when he speaks in voiceover, even more than it was on Goodbye to Language. Le Livre d’image, no doubt destined to be inhospitably translated into English as The Image Book, has none of that previous film’s bravura cinematic gestures. In form, Livre is much closer to Histoire(s) and its various extensions—for instance, Les Enfants jouent à la Russie—in that it is a montage largely comprised of images and sounds from other films, some of which, like the woman with the earrings in Boris Barnet’s By the Bluest of Seas, have recurred throughout Godard’s work for many years now. But there is a plainness and simplicity of intent here that is quite bracing. The chapter on Arabic culture is there simply because Godard wants to proclaim his love for Arabic culture, period. And he does find an endpoint, in another clip that he has often returned to, the exhausted dancer in Ophüls’s Le Plaisir, and in the sound of his own voice coughing and rasping and gasping to catch a breath. To see Le Livre d’image at the Cannes Film Festival as it is now was a moving experience, like a signal from a now distant moment. And it was absolutely startling to see film theorist, curator, historian, and professor Nicole Brenez, a key member of Godard’s team on this film, standing on the red carpet like a quiet, steadfast sentinel of the cinema behind dark glasses.

Donbass

I was impressed by Sergei Loznitsa’s Donbass, a series of blackout sketches on the actual condition of constant war that generates a very odd energy. Loznitsa was inspired by amateur videos shot and posted when the conflict between Russian-backed separatists and government troops broke out in the eponymous eastern section of Ukraine, and he and his regular cameraman Oleg Mutu (who also shot The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and 4 Months, 3 Weeks and 2 Days) cultivate scenes that begin with lazy aggression, resulting from years of hardship and unremitting terror, and gradually build into full-blown chaos and violence—every episode feels like the scene on the church steps in Shoah. Unlike last year’s A Gentle Creature, whose pursuit of the random and the lethargic resulted in a film that felt almost unattended, Donbass is piercing and impressively relentless, and its best scenes possess a believably banal and terrifying momentum—for instance, the episode of the young boy who takes us on a tour of the most squalid makeshift barracks imaginable, soon displaced in our attention by an impressively coiffed young woman who storms in to make an unsuccessful bid for her mother to join her in corrupt comfort, thanks to the munificence of the Russian politician she works for. Loznitsa’s film also reaches peaks of pitch-black humor with a power game initiated by a Russian officer who “offers” a German journalist to take back his passport, and the spectacle of a no-nonsense woman dumping a bucketful of shit on the head of a blathering small-time politician.

Donbass features a collection of generally “unsympathetic” characters, which means that it had an abundance of what was more or less this year’s common preoccupation: abrasive protagonists, from the title character in Argentina’s The Snatch Thief in the Directors’ Fortnight to the desperate homeless boy in the Lebanese Capharnaüm to the drug-sniffing troll in the Swedish/Danish Border (the Certain Regard winner) to Sinan, the deeply and believably unsatisfied hero of Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s The Wild Pear Tree. Sinan is a recent graduate in literature who returns to his idyllic but stifling country home. He wanders from one setting to another, meeting up with a beautiful and desperately melancholy young woman who is about to be married off, cornering a local literary celebrity and finally driving him mad with queries and attempts at banter and one-upmanship, engaging in a lengthy debate with two imams he meets by chance, and trying endlessly to vanquish his smooth-talking, sybaritic father. He is engaged in a classic unfulfilled young person’s practice of calling out everyone else’s hypocrisies when he is really trying to break free of himself and his own limits (never more than in the scenes in his close-quartered house, where the director shows a real gift for the staging of family warfare, one slammed door and anguished retreat at a time). I found Ceylan’s last film, Winter Sleep, to be too slavishly indebted to Russian literature (everyone kept talking about Chekhov but there was an abundance of Dostoevsky in there as well) and a little too static, but The Wild Pear Tree is an impressively mobile film: many exchanges are shot in unbroken takes as the characters walk through meadows and up and down dirt roads that wind through magnificent landscapes whose beauty renders the frustrations of this young man (very well acted by Aydin Dogu Demirkol) as so much misplaced passion.

The hero of Burning is a young Korean man from northern farm country, living in Seoul, who meets up with a girl from back home. He becomes smitten, only to find her gravitating to the orbit of a smooth, generous, and apparently easygoing rich kid. Pierre picked another great film to champion, because this free adaptation of Haruki Murakami’s story “Barn Burning” might be the director’s best film. Lee began as a novelist, and I think that his movies have always betrayed his literary origins. Burning is no exception, but every elegant contrast and parallel comes to cinematic life here, and Lee’s filmmaking has reached a new level of refinement in the eight years since Poetry. I’ll give the last word to Pierre.

“A while back, Lee Chang–dong mentions to me that he’d like to adapt a short story by Murakami Haruki, itself based on [Faulkner’s] ‘Barn Burning.’ I react skeptically. But from the opening shot, a sinuous reverse track, and from the opening sounds, we are plunged into the teeming life of a busy working-class district, at once close and distanced. Every moment will reveal something unexpected . . . Is there anything more cherishable in a film than the moment when it breaks away from what its author seems to have intended and begins to have a life of its own, with its own impulses?”

Kent Jones is Film Comment’s editor-at-large.