By Melissa Anderson in the January-February 2007 Issue

In the Cut

Frank Perry’s Play It As It Lays is hard to find, and sometimes hard to watch

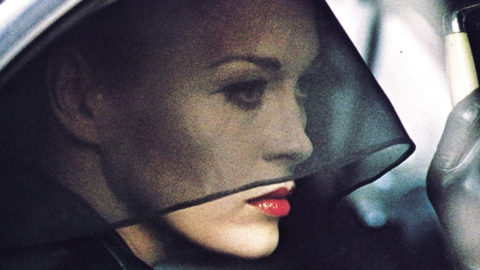

If you were to imagine a celluloid ancestor to Mulholland Drive’s Diane Selwyn, she’d probably look a lot like Maria Wyeth, the heroine of Frank Perry’s acerbic Play It As It Lays, a 1972 film based on Joan Didion’s merciless second novel, published two years earlier. Brilliantly played by Tuesday Weld, Maria is rapidly unraveling, as is her marriage to her director husband, Carter Lang (Adam Roarke). Carter has previously directed her in both a vérité short, barking bullying off-camera questions (“Did you ever want to ball your father?”), and an acid-rock biker movie called Angel Beach. As Carter prepares to shoot his next movie in the desert, Maria—which rhymes with “pariah”—drifts through a succession of ghoulish Hollywood parties and hotel-room assignations with producers from the East Coast, always returning to the driver’s seat of her banana-yellow Corvette. Speeding along the freeway provides Maria with her only moments of pleasure. She hasn’t worked for at least a year.

From the January-February 2007 Issue

Also in this issue

Bong Joon Ho’s Guilty Pleasures

By Bong Joon Ho

In interviews, Joan Didion has remarked that one profession that’s always interested her is the film editor, or, to use her preferred term, “cutter.” Cuts play a major part in both the film Play It As It Lays and its source novel. Didion wrote the screenplay with her husband, John Gregory Dunne; it was their second script collaboration, after 1971’s The Panic in Needle Park. Didion’s book is extremely fragmented, with some chapters no longer than a paragraph and the point of view shifting abruptly between the third and first person. Perry’s film, edited by Sidney Katz, expertly translates this disjointed sense of time. Some shots last only a second; chronological sequences aren’t always clear; sound and image are jarringly juxtaposed. Nowhere are these cuts more horrifically displayed than at the film’s literal moment of incision: Maria’s visit to an illegal abortionist (Roe v. Wade would be decided the year after the film’s release). The doctor’s “slicing” is chillingly conveyed as a rapid series of images: a hand encased in a surgical glove switching on an air conditioner, something tossed into a waste can, blood washed down a sink drain. This short sharp shock of a montage will haunt Maria throughout the film—as it will the viewer.

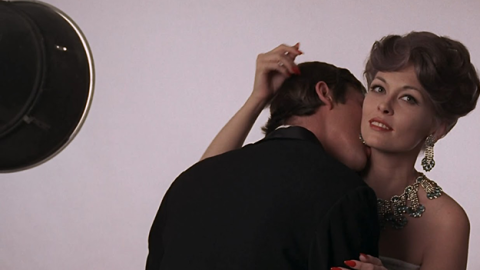

In dreams—or, in Maria’s case, nightmares—begin responsibility. “I Can’t Get That Monster Out of My Mind” is an essay about Hollywood from Didion’s first nonfiction collection, Slouching Towards Bethlehem. Maria is indeed surrounded by monstrous people, monstrous behavior, monstrous misfortune. Kate, her only child, is locked away in an institution for an unnamed mental disturbance. Her husband takes pleasure in humiliating her. “I’ve never been much impressed by catatonia as a lifestyle,” he says upon finding her in a depressive stupor; at other times he disgraces her on television and in front of a journalist. Maria herself is not above debasement: she sleeps with an unctuous Vegas power broker and with an outrageously narcissistic tv star she picks up on a tennis court. “I’m sick of everyone’s sick arrangements,” she gripes to Carter on the way home from a dinner party. This judgment is directed at herself as much as at the producers, showbiz lawyers, Euro starlets, and hunky hopefuls she brushes up against daily.

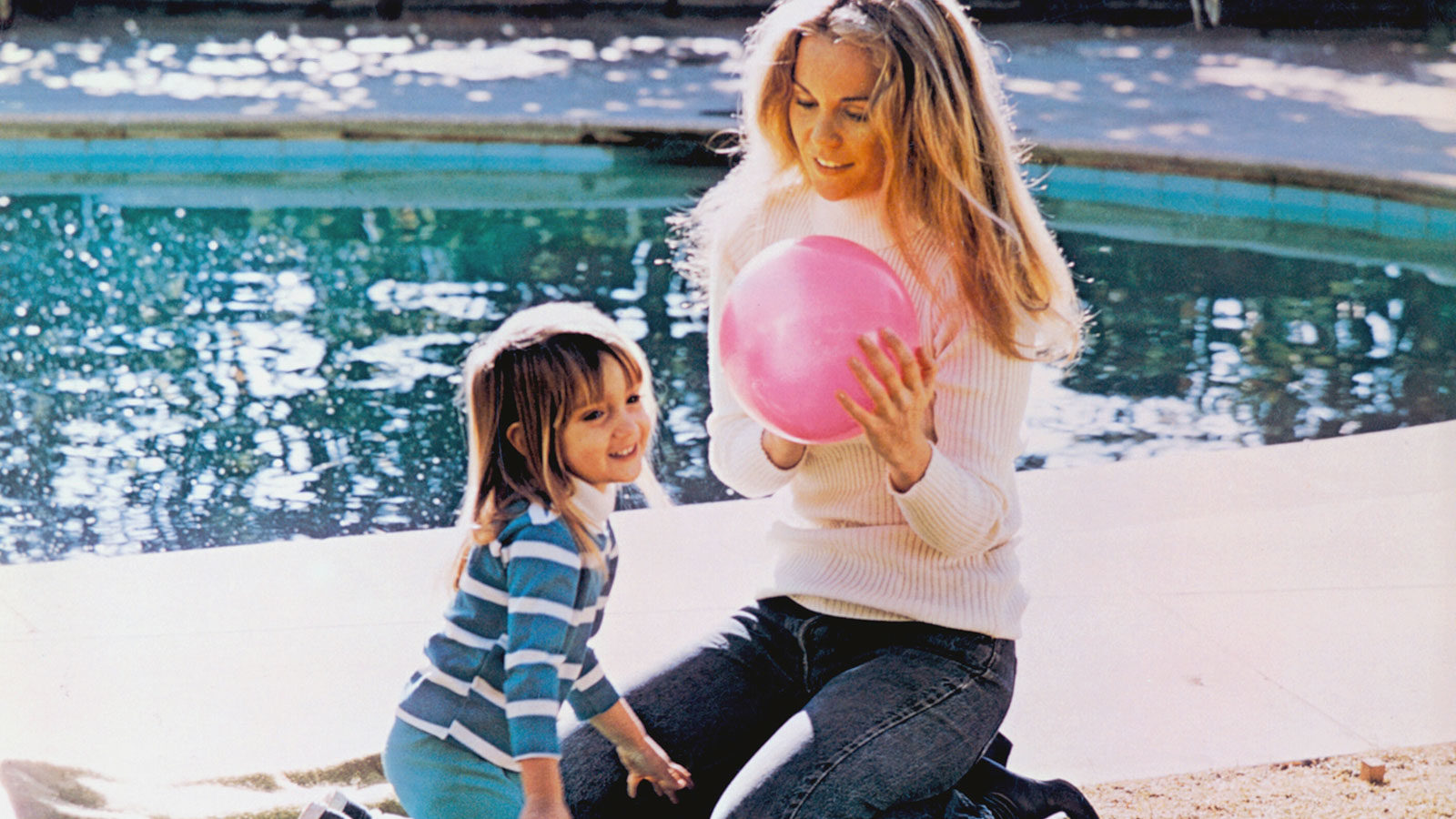

Maria, like Diane Selwyn, comes from a tiny town: Silver Wells, Nevada. With these humble beginnings came a sense of hope. “I inherited from my father an optimism which did not leave me until recently,” Maria says in voiceover, walking through the Last Year in Marienbad–type grounds of a mental clinic. Even at her most distraught, Maria still clings tenaciously to the belief that she and her daughter will be reunited someday, imagining them canning preserves together on a sunny porch. And Maria’s bleakest moments are mitigated by the one true—yet deeply flawed—friend she has: B.Z. (Anthony Perkins), Carter’s bisexual producer. The relationship between Maria and B.Z. is far more developed, not to mention tender, in Perry’s film than in Didion’s book, yet it never compromises the sting of Didion’s original prose. Rather, the expanded scenes between Maria and B.Z. provide a showcase for two actors of tremendous compatibility, further exploring the rapport they shared four years earlier in Pretty Poison.

“I know what nothing means, and keep on playing,” Maria says near the film’s end. Perry would keep on playing, too, making Mommie Dearest (81), an assessment of Hollywood that’s as grotesquely garish as Play It As It Lays is coolly austere. But what about this haunting film from 1972? Unavailable on video or dvd and rarely screened, Play It As It Lays aired last year on the Sundance Channel. Didion’s extraordinary memoir of grief, The Year of Magical Thinking, will soon become a Broadway show. But who will make this film available?