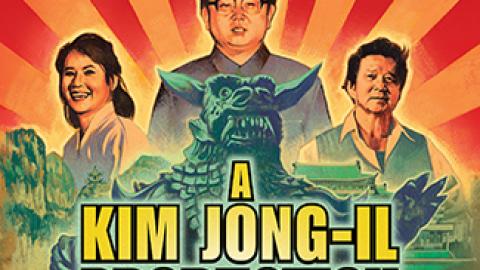

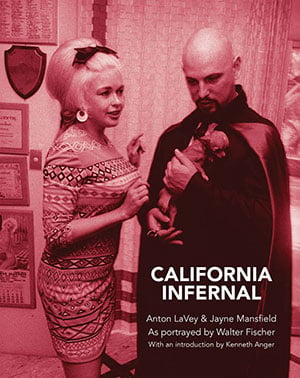

California Infernal: Anton LaVey & Jayne Mansfield

As Portrayed by Walter Fischer

Trapart Books, $39.95

Has the feebleness of so-called studio filmmaking stimulated an appetite for Hollywood backstories? I’m not thinking of the miniseries Feud: Bette and Joan so much as the crazy distortions in the Coen Brothers’ ’50s pastiche Hail, Caesar!, the tales recounted in Jon Lewis’s recent Hard-Boiled Hollywood (a scholarly riff on Kenneth Anger’s scandal compendium Hollywood Babylon), and the revived interest in L.A. memoirist Eve Babitz, whose Eve’s Hollywood is filled with promising scenarios. (Teenage Eve gets her first soul kiss from Lana Turner’s “spectacularly handsome” gangster boyfriend Johnny Stompanato, a denizen of Hard-Boiled Hollywood; she dresses for gym class at Beverly Hills High next to a girl who’d later join the Manson Family.)

Has the feebleness of so-called studio filmmaking stimulated an appetite for Hollywood backstories? I’m not thinking of the miniseries Feud: Bette and Joan so much as the crazy distortions in the Coen Brothers’ ’50s pastiche Hail, Caesar!, the tales recounted in Jon Lewis’s recent Hard-Boiled Hollywood (a scholarly riff on Kenneth Anger’s scandal compendium Hollywood Babylon), and the revived interest in L.A. memoirist Eve Babitz, whose Eve’s Hollywood is filled with promising scenarios. (Teenage Eve gets her first soul kiss from Lana Turner’s “spectacularly handsome” gangster boyfriend Johnny Stompanato, a denizen of Hard-Boiled Hollywood; she dresses for gym class at Beverly Hills High next to a girl who’d later join the Manson Family.)

California Infernal belongs with these chronicles. A collection of photographs by German paparazzo Walter Fischer, mostly from 1967, the book is rich with material for imaginary movies starring two publicity-mad gossip-column veterans: self-described Satanist Anton LaVey and Fox’s Marilyn Monroe backup, Jayne Mansfield. Forrest J. Ackerman, editor of Famous Monsters of Filmland, has a cameo, as does a Marilyn poster (as well as her grave), and the obnoxious once-notorious right-wing radio host Joe Pyne.

There’s also a disappointingly brief introduction by Kenneth Anger. Given that Mansfield graced the cover of Hollywood Babylon’s sleazy first edition (and its classier Rolling Stone reprint), one would expect a sentence or two devoted to her memory—instead it’s all about the Grand Old Man of Satanism LaVey, who was a featured player in Anger’s 1969 short Invocation of My Demon Brother.

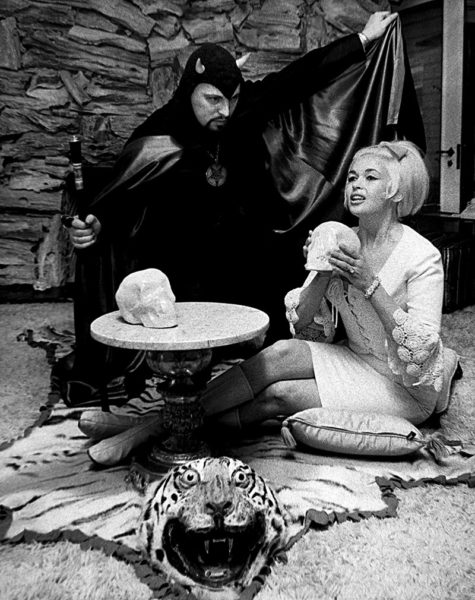

California Inferno’s main locations are the sinister Black House—a shotgun house LaVey painted to suit himself in the far west of San Francisco’s Richmond district—and Mansfield’s equally personalized Pink Palace, somewhere in Beverly Hills. The Black House scenes are all LaVey. Bald as an egg, devilishly goateed, and invariably caped, a dead ringer for Flash Gordon’s nemesis Ming the Merciless, he presides over several costumed rituals—the naked body of a female acolyte serving as altar—less suggestive of Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome than an amateur production of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Fischer was also there to document LaVey’s 6-year-old daughter’s Satanic Baptism, a homey ritual that might have been revised as an episode of Bewitched.

California Inferno’s main locations are the sinister Black House—a shotgun house LaVey painted to suit himself in the far west of San Francisco’s Richmond district—and Mansfield’s equally personalized Pink Palace, somewhere in Beverly Hills. The Black House scenes are all LaVey. Bald as an egg, devilishly goateed, and invariably caped, a dead ringer for Flash Gordon’s nemesis Ming the Merciless, he presides over several costumed rituals—the naked body of a female acolyte serving as altar—less suggestive of Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome than an amateur production of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Fischer was also there to document LaVey’s 6-year-old daughter’s Satanic Baptism, a homey ritual that might have been revised as an episode of Bewitched.

LaVey, whose disciples included both victims and perpetrators of the Manson murders, is a practiced showman. Dig the Satanic sign he flashes on the The Joe Pyne Show—the equivalent of giving Pyne rabbit ears. But Mansfield is a force of nature. As a character in Don DeLillo’s Underworld says, “she was uncontainable in a movie.”

How LaVey must have longed to get her up to the Black House. Instead, Fischer was there to record his pilgrimage to the Pink Palace. (There’s also a great shot of them making an entrance at the venerable Beverly Hills boîte La Scala.) Resplendent in a Navajo-patterned mini and white go-go boots, Jayne strikes a pose with her diminutive consort Sam Brody, a lawyer who’d be at home in the Hard-Boiled Hollywood index or lurking in the pages of Eve’s Hollywood. But mainly, it’s Mansfield—a sort of hologram of herself—showing LaVey her pool, her Chihuahua (as bald as he!), and a wall filled with framed magazines featuring her on the cover.

The obligatory ritual is fabulously sad. Wearing his horned cap, LaVey unfurls his cape as earnest Mansfield clutches a plastic skull on a fake-looking tiger-skin rug. One can only imagine what Ed Wood would have done with this material (or how Tim Burton might have handled the remake).

J. Hoberman is a New York–based film and culture critic, currently teaching at Columbia University.