Who Cares About Cinema?

This article appeared in the January 6, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

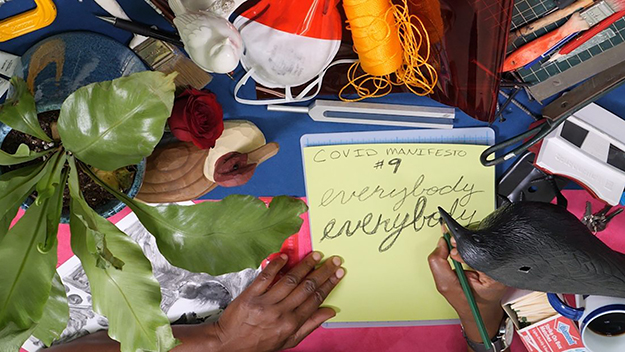

Cauleen Smith,COVID MANIFESTO, 2020, (video still) / Courtesy of the artist; Corbett vs. Dempsey, Chicago; CIRCA; and The Showroom, London

During last year’s Berlin Critics’ Week—an annual program that I’m one of the Artistic Directors for—I had a conversation on the ethics of image-making that has stuck with me ever since. Under the title “See Through,” we brought together curators Stoffel Debuysere (Courtisane Festival), Kalpana Nair (Mumbai Film Festival), and Greg de Cuir Jr., along with filmmaker Kirsten Johnson to discuss how films and filmmaking are perceived by audiences and within the industry—and the elements that elude perception. We touched upon the invisible work of curators, critics, and filmmakers in the film ecosystem and the need for “care” in our approach to artists and artworks.

Our conversation made me think of political scientist Joan Tronto’s definition of care, which acknowledges the fact that all human beings are interconnected. She articulates the need for care as a defining aspect of being human and something which contemporary societies cannot and must not neglect. For Tronto, care work includes “everything that we do to maintain, continue, and repair our ‘world’ so that we can live in it as well as possible”—a definition that likely resonates strongly with film workers, especially those who believe art makes the world a better place and justifies all kinds of (self-)exploitation. Yet the question of whether a “cinema of care” exists is difficult to answer within the actual landscape of cultural work today: it requires that we interrogate how (and if) those who act in the name of film culture relate to each other and care for each other to maintain, continue, and repair the structures that sustain the art form.

With the online exhibition Radical Acts of Care, organized for the Media City Film Festival in 2020, Greg reflected on care as a countermeasure against capitalism and as an agent for social change. The show featured work by the Pirate Care Project (which has published a syllabus on the intersection of care and piracy), Forough Farrokhzad’s The House Is Black, and Madeline Anderson’s I Am Somebody, a documentary about the struggle of unionized hospital workers in South Carolina. In our conversation, he extended the onus of care from the system to artists themselves: “There are two types of filmmakers in the world, right? Those that hug and those that don’t.” It’s a vision of care that starts with the personal. But film culture is infinitely more complicated than the actions and statements of individual directors—even if the auteurist world of film criticism and festivals often suggests otherwise. To extend Greg’s metaphor, there are also curators that hug, and those that don’t. There are industries and institutions that hug, and those that don’t. There are even images that hug, and those that don’t.

iLiana Fokianaki, founder of the research project The Bureau of Care, has been investigating the place of care ethics in visual art, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Fokianaki describes her project as a space that brings together “artists, activists, writers, and social workers to script and visualize the foundations for a European post-pandemic politics of care.” In a recent essay she argues, “Care and its politics have been a subject of concern to the art world, made all the more urgent by the global pandemic. But is it a real concern that can lead to changes in the way we operate in our institutions and working relationships, or is it merely surface level? How can care, if studied care-fully, provide solutions to the various problems that art institutions and art workers face? How is it that contemporary art institutions are keen—and comfortable—to talk about care when they have been so care-less?” It is telling that film culture, centered around one of the most market-driven of the arts, still lacks initiatives and reckonings comparable to The Bureau of Care.

As an example of film-work that inspires a care-driven artistic practice, Fokianaki cites the methodology of the Forensic Architecture research group, which positions itself at the intersection of cinema, investigative journalism, activism, and the visual arts, and which “has made truth and truth-telling a form of collective care by exposing slow and fast violence.” According to the radical logic of the group, art is never a purpose in itself, but a means to an end—an aesthetic tool for visualizing facts and altering reality. The group caused a scandal in the artworld in 2019 with their video investigation “Triple-Chaser,” which exposed the connection of Warren B. Kanders, vice chair of the board of trustees of the Whitney Museum of American Art, to the violence perpetrated by the U.S. government against migrant families, and resulted in his resignation from the board. When Fokianaki invited the group to Athens the same year, they presented—in the form of video installations—the results of several investigative projects highlighting how realities of violence are not just part of conflicts and wars but also of democratic societies around the world, albeit in a more subtle form, as slow violence. Inspired by Rob Nixon’s book of the same title, the notion of “slow violence” is closely related to the concept of care, in that it invokes its opposite: the suppression of human rights and dignity through capitalist systems that neglect society’s responsibility to care for the ecosystem of the planet as a whole.

Even as care—in the contexts of class, race, gender, and more—becomes increasingly relevant to cinematic representation, the actual work of making cinema, from film festival programming to below-the-line production jobs, lags far behind. Recent steps forward have notably been based on personal initiatives rather than sustainable models within the system. It wasn’t until 2019, during the 72nd edition of the Cannes Film Festival, that festival attendees were able to access child care—when Aurélie Godet, Sarah Calderon, Olimpia Pont-Chafer, and Michelle Carey launched the “Parenting at Film Festivals” initiative, which set up a day care for the children of festival attendees. The initiative was inspired by a similar playhouse launched at the 2018 Sundance Film Festival by the Moms-in-Film group. At Cannes, the facilities for the nursery were provided by the Marché du Film, while the costs for the child care itself could only be realized through a crowdfunding campaign.

Currently, numerous visionaries are fighting for a stronger understanding of care within cinema and cultural work. In his recent manifesto in Film Quarterly, Girish Shambu—an important advocate for sustainable cinephilia—writes: “‘Life organized around films’ is one widely accepted definition of traditional cinephilia. But at this moment, when the world is in turmoil and the planet on the edge of catastrophe, such a conception of cine-love seems irresponsible, even narcissistic.” Shambu’s text provokes some painful insights: while many cinephiles, myself included, envision their passion for cinema as a labor of love, it is necessary to examine whom this love—and this labor—ultimately sustains, and whom it depletes. The same questions drive the efforts of Jemma Desai, the current program director of the Berwick Film Festival, who sparked debates by publishing a lengthy anti-racist study in 2020, titled “This Work Isn’t for Us.” Based on 15 years of working in the arts in the U.K., Desai illustrates that even in cases where institutions have addressed questions of diversity, they have implemented initiatives without care for those who bear the responsibility for executing change: cultural workers. In resonance with Shambu, Desai describes the British arts industry as “a hostile environment that increasingly seems to privilege self-interested individuals in a market economy rather than nurturing a network of relationships between people. It is now clearer than ever that these are the things we need to take care of, to articulate and to fund. It is not enough to be diverse and multiplus, it is not enough to display this visibility without care and understanding.”

At the beginning of the pandemic, as more and more arts institutions and film festivals shifted their activities online, Cauleen Smith (who was featured in Radical Acts of Care) stated emphatically, as part of her COVID MANIFESTO series of artworks, that “The Internet Is Not the Answer.” Smith’s project underlined the need to respond to the pandemic with a strengthening of the bonds of social coexistence through dialogue, as opposed to an unconditional embrace of the isolating algorithms of the digital economy. Without a fundamental understanding of film culture as a milieu of social and communal experience, the need for care cannot be acknowledged. Internationally, film critics and the festival industry have been hard at work parsing the shift of viewing habits with the advent of online festivals—an already outdated discussion that has existed since the rise of television. If the pandemic continues to drag on or brings about a permanent change to festival programming, the question becomes: how do streaming events and online film festivals reinforce a perception of cinema as an industry rather than an essential artistic and cultural practice? Only an artistic and cultural practice allows for and requires an ethics of care—for the artists, for the work itself, and for the workers who sustain it. As Martin Scorsese, a filmmaker intimately familiar with the demands of industry on art, succinctly put it: “We can’t depend on the movie business, such as it is, to take care of cinema.” Whom that “we” includes and implicates is the pressing question.

Dennis Vetter is a film critic and programmer. He is a board member of the German Film Critics Association, as well as a co-founder and one of the Artistic Directors of the Berlin Critics’ Week. Since 2009 his writing has appeared in numerous magazines and newspapers.