Venice Interview: Véréna Paravel and Lucien Castaing-Taylor

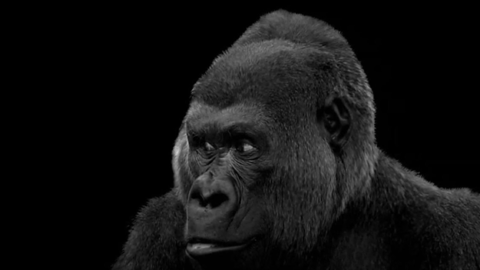

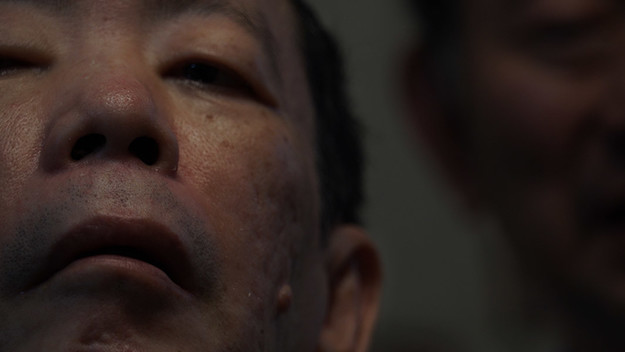

As far as cannibals go, Issei Sagawa has done fairly well for himself since murdering and eating a Dutch woman whom he befriended in Paris, in 1981. Now living in Japan though ailing, he has supported himself for years through his celebrity and stories of his exploits. Lucien Castaing-Taylor and Véréna Paravel, directors of the differently immersive Leviathan and Ah humanity!, decided to turn their cameras on Issei Sagawa. In Caniba, the pair sought to make a subtle film about cannibalism, shooting the film almost entirely in close-ups, a talking head in which (as they explain) the head is not always talking. But that’s half the story: Issei Sagawa’s brother, Jun, who looks after him, becomes a kind of interlocutor, one who introduces to the story his own unusual proclivities. A sequence of 8mm home movie footage and a key story involving their mother also serve to explain everything and nothing.

Film Comment spoke with Castaing-Taylor and Paravel about the film’s aesthetics and ethics beachside at the Venice film festival, where it had its world premiere. Caniba screens at Projections at the New York Film Festival on October 8 and 9.

How did you know this was something you wanted to do a film about?

Véréna Paravel: When we try to recall exactly how things happened, it’s always like trying to retrieve foggy memories. But: we were working already in Japan—we had this commission from a French art foundation, and we were supposed to do something about Fukushima. It ended up being a piece we made called Ah humanity!. So we were traveling a lot in Japan and we got interested in many things including sumo and pinku eiga. This genre pinku eiga is unique to Japan and super interesting, because it’s shot in 35mm and it’s a very special way of shooting, very low-budget. All the masters of cinema in Japan started by doing this, including Kurosawa. So we were really intrigued by this genre, which was on the decline, and we ended up meeting a couple of pinku eiga filmmakers. We got interested in this one filmmaker, Satô Hisayasu, who is super controversial. And then we realized that Issei Sagawa was acting in his film!

Lucien Castaing-Taylor: And we remembered Issei Sagawa from growing up in France.

VP: Issei Sagawa is a super well-known figure in France. I remember him from when I was a kid.

Is he like John Wayne Gacy in the United States or something?

VP: Yeah! He’s like this cannibal figure, he was all over the place. And in the mind of a 10-year old child, when you have a cannibal…

On the loose?

VP: Yeah! So, because we were interested in pinku eiga, we decided to produce a film by Satô Hisayasu in which Issei Sagawa would act. This is how we got to know Issei Sagawa. And that was the deal: we produce a film of yours, but you let us shoot while you’re shooting. While you’re making your film, we’re making our film. So we have 200 hours of footage of a pinku in the making.

Like a behind the scenes.

VP: Yes. But we haven’t edited that yet—maybe we’ll edit it in 10 years, we don’t know. But we got to know Sagawa, and this is how everything started. We wanted to collaborate with him, so we started to research him and what we could find was this very horrifying, sensationalist representation of this oriental monster. We had a discussion saying we would like to try to give you the floor to express yourself in a way that maybe you haven’t had the chance to. And we didn’t know how far we could push the collaboration and we were really open to anything. We knew he wanted to be eaten and to die that way, and I imagined that he possibly wanted to die and be eaten. So it was this very open collaboration where everything was possible.

Everything was on the table, so to speak?

VP: Everything was on the table, exactly.

Did the sensationalist coverage bother him though? Because in some ways he seems unselfconscious. I’m trying to find out the appeal to him of being consumed by your camera in particular.

LCT: I don’t think he knew us from Adam. I don’t think he knew who we were. He was willing to trust us, provisionally, because of our relationship with Satô Hisayasu, who’s the last person that he trusts. But I think he has a very deeply conflicted relationship with the media so he maintains, not inaccurately, that he’s been misrepresented. The lion’s share of media representation has misunderstood his desire. Not that he’s innocent or anything. But he doesn’t know anybody authentic or any portrait in which he recognizes himself—and he resents that. At the same time, in the last 10 years, he hasn’t been quite present in the media, but for the first 10 to 15 years in Japan—after he returned to Japan—he actively sought out media attention, both in cannibal and in sexual exploitation films, and in appearing on talk shows and talking about it and rarely expressing any remorse. He was self-diabolizing: he was playing the part of the monster for whatever media attention he could get. And in part to make a living—he would occasionally get paid for this. And in part because he’s a deeply complex subject.

Has he seen the film?

VP: We’ve barely seen the film.

LCT: Yesterday was the first time we got a screening.

When did you have a finished version?

LCT: The press screening.

It’s interesting about the self-diabolizing image, because he comes across as childlike, especially toward the end. Does he have a different manner, at home versus in public or something?

LCT: There are lots of different manners, lots of different dimensions to him. I don’t think it’s home versus the world or home versus public. I think on the one hand, he’s very thoughtful, he’s deeply cultured and well-read, but there’s something childlike in his manifestations, innocent at times. Part of the problem of the media’s representation of him is they haven’t [understood him]: although he recognizes that what he did was grotesque, he believes that behind his motivation is a kind of non-abject innocent desire, somehow, a pure desire.

I like the wisdom he ruefully expresses about cannibalism: “I wish I’d understood that I didn’t actually have to kill her.”

VP: Don’t you think this is actually kind of a comic film? Somehow?

Oh, it is!

VP: Yeah, we were laughing! Then I suddenly felt selfconscious of the way we were laughing. I found it profoundly hilarious most of the time. Some lines are just out of this world.

LCT: “Would you not want to eat me?”

VP: Yeah! Why don’t people laugh? Why are people so serious?

I love that whole experience because as soon as you realize that the brother’s a masochist and he’s a sadist, we think, “I think I see where this is going…”

LCT: “God forbid you should live too long!” “Don’t eat so much! Die, die!”

VP: Fred Wiseman has seen a cut of the film, and he was laughing all the way through.

I wanted to ask about the film technique. It’s interesting to hear that you shot it while working on the pinku. Why did you choose to shoot predominantly close-ups? I don’t know—just putting that out there.

VP: You don’t know. We don’t know too.

Well, I have an idea.

VP: Can you tell us?

I felt that it was the screen made flesh, basically. So from the very beginning, most of the screen is just flesh—it’s just all there. You’re confronting him bodily and making the screen corporeal in a way.

LCT: I think you’re right. I think it’s flesh and landscape, with the landscape of the face and the physiognomy at the same time. I remember, after a friend of ours saw Leviathan, he said he couldn’t watch it a second time. He said, “You just retreat from the verbal at every possible [moment]—you’re so scared of words. Your next film has to be a talking head interview.” Well, it became a non-talking head in this film. And where Jun tries to take over, discursively, in their rivalry, he doesn’t succeed, and neither does Issei Sagawa let him succeed—he puts him down at every point. He himself is very laconic, and speaks in haikus and fragments and so on.

But it’s also about basically the phenomenology of desire—especially in this case a sexual desire—which can’t really be expressed in a typical documentary expository, or even fiction narrative language, in any straightforward sense. So I think by concentrating on the close-up, at the same time, you’re privileging the voice—the mouth is usually visible. We’re also encouraging attention to the way in which affect, identity, and subjectivity communicate through a face that is fundamentally non-verbal.

It’s the first time we’ve worked in a language that we didn’t understand at all. We collaborated with our friend who did the sound, and he would whisper, in our ears, what was being said at our request. And then other times we would say, “Please don’t translate. You can’t—we don’t want to know what’s being said. It’ll basically obliterate our non-linguistic apprehension of what’s going on or what we’re perceiving here.” So there’s this willful denial, even though we’re dealing with the genre of the talking head—but subversively, by not privileging language.

VP: This is exactly what happens when you’re deprived from understanding the meaning of what is said. Suddenly you have to create your own universe and you just focus on what is left, besides the word. But then you’re left with the landscape of the face and you’re just trying to grab onto every single thing that is given to you through the skin, which is our most immediate relationship to the word.

Yes, and there’s also the way in which he phases in and out…

VP: Exactly! And you see him going backwards sometimes and coming back, and is in and out of focus. It’s about his presence and his absence, and our presence, our being there and not listening or understanding, so also being very absent. Sometimes you see him going somewhere else—you don’t know exactly where he is but he’s not really there.

What was the camera setup?

VP: It’s a very small space.

LCT: He has a bedroom which is a warehouse that’s just filled with unopened and semi-opened boxes so he doesn’t use it. He sleeps in the living room, which is attached to the kitchen. It’s the same space, I’d guess it’s five meters by four, so 20 square meters. And a toilet. That’s it. That’s the extent of his universe for the last five years.

VP: It was the two of us filming at the same time.

LCT: One of us in his wheelchair.

VP: We were fighting to get it!

LCT: Each of us was recording sound and image at the same time.

VP: Yes, this is the first time that we’ve done that.

What kind of cameras were you using?

LCT: DSLRs. Sony A7S.

VP: We love it, but the focus is also pretty hard to work with. And I’m losing my sight.

LCT: In documentaries like this in uncontrollable situations, it’s impossible to keep the subject in focus.

VP: Even with my glasses, there’s no way I can focus on anything. So we’re trying to find some theoretical approach to the…

The orientation?

VP: Yes.

Physically, how close were you to him when you were filming?

VP: The bag is here and the table is here [points to cafe table in front of us]. He’d spend his day eating, going to bed, watching sumo.

LCT: Takes about five minutes to get to bed, with a helping hand or two.

You don’t do any long shots of the warehouse.

LCT: We had lots of wide shots, we didn’t know how to express this, so we did film in other ways, inside the home and outside the home, the walls, but not much more. We felt that whenever we were exploring space, it was legible to the spectator—and to us in watching it later—that it was motivated by our own intentionality, rather than as emerging organically. So we’d be looking at girls he’d fantasized about or religious icons or various kitsch artifacts he’d collected over the years.

VP: Bambi. Cinderella.

LCT: Pictures of naked ladies and lots of different things. It was just so obvious that it was either evidence or A-roll, B-roll.

VP: I also do believe that we were somehow shy to film his body.

LCT: We did film his body.

VP: But at the end, we didn’t use it. And I really feel that we were shy with his body because he has a very weak body.

His face has a certain majestic solemnity to it sometimes, so I can see how showing his body might detract from that perhaps.

LCT: His face also moves back and forth in the viewer’s mind between the playful and the monstrous to utterly abject and very feeble and fragile at the same time.

Often we can’t really see his pupils or his eyes.

LCT: And the few times when you can, in crystal clarity, it’s deeply disturbing as well.

Now, I know probably nothing’s more bourgeois than bringing up Freud… but Issei Sagawa seemed like the textbook example of how Freud defines fetishism and how a fetish arises. It’s basically him. The story about his mother seems to affect him deeply. But I don’t mean to diagnose him.

VP: Yeah, we quite avoid that. And I think in this film you are very often put in a position where there are elements that you have to diagnose, as you said, but you can’t. It triggers your imagination that there is nothing deterministic or rational in terms of an explanation. We really tried to avoid all these direct references.

For me, the 8mm footage, how do you say vivier [breeding ground]? It is like a place where things can come alive and you can grab things or not and you see this man giving this [vaccine] shot and there’s this whole universe you can access but not really. You cannot understand who these people are, from your childhood, so you can make connections, but the connections you make are not plain, simple explanations. So at the end, you still wonder, you still have mystery.

I just completely blanked on what I was going to say next.

LCT: That happens to us all the time.

VP: You’re like us! Very reassuring. [Laughs]

Gravity! You mentioned the word gravity in the director’s statement.

VP: Ah yes, the seriousness, the seriousness or gravity?

LCT: There’s a film called Gravity isn’t there?

Yes, there is.

LCT: People compare it to Leviathan. It’s the one in space?

Yeah. The sound is the most interesting part of that movie for me. They have these synth chords that last forever… But back to Caniba, what do you mean by gravity precisely?

LCT: If there’s any element of gravity, it’s a species of innocence or seeking to disrupt a form of moralism that disallows any real curiosity or can motivate a distinct desire. So we have to say that he’s abject, that he’s monstrous, et cetera. And how could we possibly give him airtime? Why would we spend time with him, why would we be his mouthpiece? Blame the messenger, essentially. It seemed to be the kind of moralism that refused to take what he does seriously or engage with his being, with his humanity. It’s a form of moralism that’s cowardly and unethical. It’s not just unphilosophical, it’s unethical on a multitude of levels. So I think “gravity” is a kind of simplicity as well, in this case.

Cannibalism does seem to be one of the last taboos in terms of, let’s say, alternative lifestyles.

LCT: I mean, it happens very occasionally between non-consenting parties. It is still illegal.

Why do you think that is?

LCT: Because it involves murder. Just because I want to be murdered doesn’t give you the right to murder me.

Issei Sagawa seems to think that maybe he didn’t have to murder her.

LCT: But that’s part of his equivocation and moral ambivalence about desire, and his efforts to come to some kind of moral reckoning with it. And the unwilling nature of his consummated but continuing desire.

How do you think this fits with their religious belief as well? At some point he says he’s too dirty for Catholicism. What you think he means by that? I thought of flagellation right away when I saw his brother with the barbed wire. And you include clips of his attempt at pornography—you can see two crosses on the wall in the medium shot.

VP: My favorite shot. I don’t know if they really have a clear understanding of the way they were brought up, as Catholic, or being too dirty. I don’t know if they have any way of self-understanding or analyzing their relationship.

LCT: We never heard Jun expressing this sentiment.

VP: That’s true, but there was one thing that is in the manga—I don’t know if it’s in the film still—but when he killed her, the first thing he ate was her clitoris. And when he swallowed her clitoris, he was talking about communion. So we can make those connections.

Issei Sagawa’s manga is really also interesting because he paints himself as this little orange demon. It’s a very strange way of representing himself.

LCT: He completely self-orientalizes himself, really profoundly.

The comedy aspect also comes up with the manga. I love Jun’s fine distinctions, that this manga is just too much. Comics are supposed to be funny!

VP: This is what triggers his will to tell us and his brother about his own condition. After reading the manga, he decided that it was time to make public to his brother the revelation of his own condition, so there also was a moment of communion here, between the two.

That was a bit of a meta-comic moment to me, too. To this point, we’ve been watching an unusual movie that’s different from most any we’ve seen. And at this moment, you have the kind of revelation scene from a more conventional documentary, or even a reality show: that scene of “There’s something I have to tell you.”

VP: Yeah, yeah, it is!

Then at the end, you introduce one more element, the woman dressed up as a maid. What’s her relation to Issei?

VP: She’s an old friend.

Sounds like film noir.

LCT: She’s an old soul. [Laughs] They were very close for a few years, and then, like with most of us, they drifted apart and remained in occasional contact. Then while we were there filming in Japan, she heard from him and he expressed to us an interest in connecting with her. And then she came over.

That’s kind of sweet.

LCT: Well, we don’t know what that relationship is since we left…

So you may have rekindled something.

LCT: [Laughs] Cinéma vérité!

VP: But after the fact, we discovered this story that she’s telling him. She was recounting a part that she played in a film. She was a zombie.

She’s an actress?

VP: She’s a pinku eiga actress.

So this is another kind of story you introduce to the film. To that point you have his story, you have the manga, the pornographic fantasy, and now you have this zombie fairytale.

VP: It’s a zombie fairytale where she can only live by eating human flesh. And she’s condemned. It’s actually extremely beautiful the way she’s telling the story and the way he’s looking at her and desiring her.

We’ve up-ended everything we think about a possible villain of a fairytale or zombie movie. When she tells that story, it’s no longer about a villain. It’s about a human being that’s in front of us.

LCT: That’s far away from us.

How much time were you filming just with you and him?

VP: I don’t think I can be precise because we were shooting the pinku with Satô Hisayasu. We spent a month and a half in Japan but we saw him several times. And we met him first and we had dinner with them.

What did you eat?

VP: Sushi. [Laughter] Raw fish. And he’s eating more than the three of us combined, us and our colleague.

LCT: He just has a big appetite.

VP: It’s actually quite staggering to witness, completely insatiable, like he needs to feed himself.

It’s funny because you only have the one scene, the opening scene, where we hear him eating, right? But after that, I don’t remember any others.

VP: Yes. There were some more and we were suddenly worried that it would be easy to connect like, “Oh, he’s a cannibal. He’s eating.” We are always trying to be subtle even though we don’t succeed all the time. And we saw him several times—we’d go in the morning, leave at night, come back in the morning.

What kind of relationship did you develop? Does it feel like routine for him?

VP: I don’t know that there was any routine because every day was very different. It depended on how he was feeling. He could be super tired, he could be more laconic or less laconic, the mood fluctuated a lot. And their relationship also developed in a different way because of the relationship with our relationship and the revelation of the manga. So it was evolving through time, and they got to know us a little bit better and we were more at ease with them and trust builds. But no routine—we were worried about disturbing him. He was tired sometimes and we would let him sleep and be quiet for a while. Sometimes we would spend hours filming him in his silence. His ability to express himself in words and his inability to do so was as interesting to us.

There’s a lot of silence and talking off screen. We’ll see Issei here and Jun talking off screen.

LCT: We didn’t understand what they were saying. And there’s nothing more boring than looking—it’s always more interesting, if you’re talking, to look at her [Véréna] listening to you than it is to look at you. And if she’s talking, than it’s much more interesting to look at you. Sometimes it’s deliberate and sometimes it’s completely random.

VP: Imagine you’re filming us too and you don’t understand a word of what we’re saying, for hours. You’d be so bored!

LCT: Even if you do understand!

One last question. I kind of have to ask, after all of this, did you think of Issei Sagawa as insane or sane anymore? Or neither? Is it more a form of sexuality?

VP: Why are you interested in that?

LCT: I don’t know why you would ask Nic why he’s interested in it, because I think we are both deeply interested in it.

VP: Of course we are! But I am curious.

There are many different angles to look at it from—aesthetics, philosophy, religion, psychology, which I’ve avoided until now. It’s possible he’s not insane. You used the word “condition” before…

LCT: We’re now making a film inside the human body, having medical imagery and surgery and stuff. We started trying to meet with people in Boston, in hospitals and so on. And I remember, we met with the director of McLean, the psychiatric hospital, and I made the mistake in saying we were really interested in—

VP: In insane people.

LCT: And rethinking and questioning the distinction between insanity and intelligence. The doctor was very intelligent, academic, and her son is a filmmaker at Harvard, etc., etc. And she was immediately horrified by my use of the word “sanity” and “insanity” even if I was seeking to relativize the distinction. And she said, “We don’t talk about sanity or insanity.” Basically, within the psychiatric and the psychological world, the word sanity and insanity have been banished. It has been abolished. What we were desperately seeking was to reflect on these questions. I suspect that what you just said we might concur with.

VP: He thinks he’s insane.

LCT: A number of times. But to say that doesn’t mean to say that we’re normalizing anything that is distinctive or singular about it at all or abhorrent as well.

VP: No.

LCT: But I think there’s a real danger in speaking under the table all these questions about sanity and insanity as well.

The word “mad” also has a romantic aspect to it that’s not clinical.

LCT: To say that he’s mad, it is Il a la folie: “He has madness.”

VP: He has madness, which in French is very broken in this Stranglers song [played before the credits at the end of the film]. As if it was something—

That you catch?

VP: Yes, as though it is something that you catch!