The Mystery of the Great Pyramid

Turn your watch, turn your watch back

about a hundred thousand years.

I’ll meet you by the third pyramid

Ah come on, that’s what I want

—The B-52s

There is a terrifying shot in Land of the Pharaohs. It comes just before the last shot of the sequence in which Queen Nailla sacrifices herself to save her son, Prince Zanin.

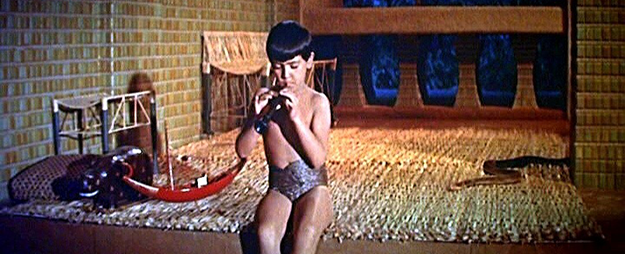

Interior, night. We are in the Pharaoh’s palace. Sitting cross-legged, still and naked, the small prince plays a flute that was offered to him by Princess Nellifer, the Pharaoh’s young mistress.

Concentrated like a little hieroglyph, he repeats the only song that he has learned from the Princess: a simple, hypnotic children’s melody. The warm air of the Egyptian night is slow and heavy. His mother, the queen, makes his bed, folds the towels, listens and smiles. One cannot tell how much time has passed until a dark-skinned man with sparkling eyes appears from behind the balcony curtains, carrying a wicker basket with a snake. Freed from the basket, the reptile slithers through the mosaic, enchanted by the music. The mother strokes her long black hair and tells her son that it is getting late. The child asks to stay a bit longer and continues to play his song—he makes a mistake and stops playing. The snake stops moving. He starts again and the snake keeps coming closer. It is already too close when the mother notices it. She doesn’t have much time to act. Then something strange happens: the mother moves slowly towards the danger, repeating to the child, as if in a whisper, “don’t stop playing,” “it’s so beautiful,” “don’t stop…”. She moves to the cadence of the music, like the slithering of the snake. These movements in three different times become for a brief instant one single time. The shot that follows lasts only two or three seconds, maybe less. With superhuman strength she flies through the room and throws herself upon the snake, right next to the child. Suddenly the image fades to black, as if hell had frozen over. We hear a scream and see a gesture of relief—Princess Nellifer takes a deep breath.

It is not really possible to tell everything that happens in this shot. It is not the whole image of Land of the Pharaohs, but all the film is contained in it. The pressure of Time and Death expressed in the shot and in the film explodes in our faces. It is like an open wound that keeps tearing wide, a wound that was already there from the start, that won’t be healing anytime soon. Like scars that remain on the surface of the skin, as carvings on a stone.

There is no cure; we can’t help but see.

There must be a limit beyond which the static, frontal, ascetic image becomes unbearable, where that invisible line, that open wound, will always remain. Time and space become saturated, full of emptiness, forced to face each other and do battle. There is only one thing left for an image to do: to become a gesture, to be constructive or destructive. Such a movement will always be beautiful and ruthless. Howard Hawks was a wise man. He knew the secret. It took him many years of living and many films to prepare for this deadly confrontation.

Face to face as in a duel, like the one fought in his following film.

He knew that he would have to face off that inscrutable face, those bones turned to dust waiting for him in that hopeless street, staring back at him, in silence.

His duel with the Absolute, to which he gave such magnificent expression in Land of the Pharaohs, left him with a deafening violence in a blind terror that never went away. A man dreams about the Absolute, submits to its cosmic rhythms only to get lost.

The shot that frightens me so much is preceded by a close shot—one of the few in the film: a tracking shot of the beautiful face of Queen Nailla. Time dilates and compresses, it becomes elastic, multiple, and Hawks’s camera does not allow us to move away any quicker. We feel like we should be able to help her if only because she is the one who keeps the secret without being able to find a way to reveal it. She is both light and shadow, she knows of the ancestral curse, she remembers everything, she brings destruction with her, and we should be able to move faster, that is, if we still want to save the beautiful and ill Nailla, living among the dead. Slowly and suddenly, the absolute fear she displays becomes clouded by something even more terrible: a brief but visible smile spreads across her thin lips—a movement. But the shot doesn’t try to help her, there is no wish to bring her over into the next shot. Hawks cuts and edits. When she flies through the room it’s an entirely different matter—she was already there starting from the cut: she is at the same time what is and what isn’t, what was moving and what will now stop moving. Precise, fleeting, and innocent. Dead among the living. She disappears into the darkness and we are forced to forget her sphinx-like face. I wonder why that is? And yet there must be somewhere another woman who is finally able to breathe deep in relief. Hawks, the man, did everything he could in that single shot. He filmed the most ancient and the most modern, immobility and movement, time standing still. He chased a rebellious fusion of opposites, the pure despaired beauty of a gesture. But where does that smile come from? Make no mistake: there is never a second of suspense in Howard Hawks’s movies: we expect death to come, we run towards it and that is all. Nobody leaves or enters a shot by Hawks: we are trapped in them and don’t come out alive. Hawks is a hard worker: he builds his shots brick over brick like a mausoleum, like a huge graveyard. But a pyramid takes such a long time to build. It is a science of nightmares. A man dreams about the Absolute and gets lost in it.

Land of the Pharaohs is a long nightmare. It is a dark film, asphyxiating and cursed from the moment it starts. In order to gain access we must lose ourselves. Hawks, half blind and dumb as his architects and high priests, guides his fragile and nervous Pharaoh by the hand through the secret chamber corridors, through the large mastaba. They are veiled and protected by the massive and monolithic stone sphinxes who watch them alternately from the right and the left side of the frame, shot by shot.

Outside by the light of Ra we see from the top of the pyramid the serene, impenetrable and distant Egyptian peasants and laborers lining up, draped in brown and ochre by the great Trauner, slightly darkened by basalt rock and fulminated by the photographic magic of Garmes and Harlan, soiled by time, climate, and toil. The builders of the Great Tomb are building their own grave, moving in a march as long as the Nile filmed in a majestic slow shot. They are trapped in the frame, thousands of inhuman arms and torsos and legs seen in the distance with their hieratic profiles, closely watched by Osiris, Isis, and Aton, with the sound of their voices coming from beyond the grave, cinema voices.

We never follow the Pharaoh through the Valley: Memphis, Thebes, Heliopolis. We are not allowed to see his treasures, to live his adventures. We are trapped in the shots and the keys of life and death have been lost. A pyramid takes such a long time to build… Montage of attractions, stone over stone, the images dissolving in each other as if in a dream. Everything is so heavy and real because time is carved into the film, guaranteeing us that all of them are already dead: we can see Land of the Pharaohs over and over again, but all those Egyptian extras will already be dead. Watch them dissolve, as grains of sand, grains of time, Egyptian-seconds, Egyptian-minutes, sons of the Great Desert where all our future films will be shot. Space and time are Land of the Pharaohs’ main characters: the Great Pyramid will stand forever, protecting the dead from the living. Khufu’s conflict is against time. This Pharaoh is none other than the brother of Scarface, a poor hoodlum. Crossing once more the antechambers of tall columns, he is only fighting to keep himself together, he is nothing more than a rotting carcass; he just wants to pack up his own corpse, to keep a fine balance between the stiff posture of a semi-God and the pathetic drunken fall of that old, stuffed Jack Hawkins. He wished to give some dignity to the time that he has left. The hauntings return and so do the close-shots: they are like déjà-vus inside the grave that hides this nightmare. Shot: the Pharaoh soaked in blood against the golden rings of a solid column, his bovine face covered with sweat and disfigured, his eyes as stricken with fear as Scarface’s. Counter-shot: Princess Nellifer, who by nature will never be able to put to rest her pin-up posture, is a secret, the Pharaoh’s special secret. And what had already happened, happens once again: time stands still expanding in every direction; all the rhythms are different and co-exist in the same shot: the impotent gaze of the Pharaoh is directed towards this woman who is covered in his own treasures. A smile spread on her face. Because he doesn’t have any other choice, Hawks performs the ultimate sacrifice of cinema: he doesn’t cut or fade out the image. Her voice doesn’t come from her mouth, we slide from pleasure to ecstasy, obscurity becomes even more obscure and the face of Nellifer goes out of focus and loses definition, loses its identity.

The Pharaoh is already dead and he hasn’t even noticed it. Who is this woman?

I would rather not know!

Land of the Pharaohs is the story of a man who is obsessed by keeping the greatest secret, but who can’t hide a thing from his best childhood friend. Like his hero, Howard Hawks gets lost somewhere between the small code of conduct that he had followed all his life and the Great Code whose key he probably never found.

William Faulkner, the scriptwriter of this film, wrote: “All of them looming among the lush green of summer and the regal blaze of fall and the rain and the ruin of winter before spring would bloom again, stained now, a little darkened by time and weather and endurance but still serene, impervious, remote, gazing at nothing, not like sentinels, not defending the living from the dead by means of their vast ton-measured weight and mass, but rather the dead from the living; shielding instead the vacant and dissolving bones, the harmless and defenseless dust from the anguish and grief and inhumanity of mankind.

“It’s like there was a kind of cosmic rule for poverty like there is for water level, like there has to be a certain weight of bums on park benches or in railroad waiting rooms waiting for morning to come or the world will tilt up and spill all of us wild and shrieking and grabbing like so many shooting stars, off into nothing.”

Translated by Ricardo Matos Cabo and Andy Rector. First published in HOWARD HAWKS, Cinemateca Portuguesa, coordinated by João Bénard da Costa (Lisboa: Cinemateca Portuguesa; Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1990). Land of the Pharaohs screens on Tuesday and Thursday in the carte blanche program of “Let Us Now Praise Famous Men: The Films of Pedro Costa” at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.