Telluride 2017 Journal

Lady Bird

This year’s Telluride Film Festival—the 44th edition of the intimate annual Labor Day weekend event held in the well-appointed Colorado mountain town—was a kind of homecoming for Barry Jenkins. Stars famously walk Telluride’s streets and are rarely approached, but while out and about Jenkins was frequently greeted with hugs.

One year ago during a casual party hosted by distributor A24 at a popular local Italian restaurant, Jenkins canvassed the room for first reactions to his new film, Moonlight. Six months later it won three Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Adapted Screenplay, and this year Jenkins was back for a victory lap at the festival where the film had premiered.

A curator of shorts at Telluride again for the fifth year, Jenkins was also in town to pass the torch. Jenkins ducked out of this year’s A24 soiree a bit early to catch a screening, but staying behind at the same Italian spot was Greta Gerwig, whose solo directorial debut, the autobiographical Lady Bird, emerged as one of the best-received movies of the festival.

Jenkins tweeted in support:

LADY BIRD is all kinds of lovely. At once a no bullshit depiction of working class strain on life/love/family and…just romantic & lovely

— Barry Jenkins (@BarryJenkins) September 2, 2017

A handful of new narrative films garnered attention from festivalgoers in Telluride, but, it was the ones rooted in reality, like Lady Bird, that were among the best of this year’s offerings.

That Summer

Of the lineup—which, as always, was announced on the first day of the festival—Göran Hugo Olsson’s That Summer was one of titles that aroused the most curiosity. At the center of the latest documentary by the director of The Black Power Mixtape 1967-1975 and Concerning Violence is footage from four previously lost reels featuring the subjects of the Maysles Brothers’ Grey Gardens, one of the most acclaimed documentaries of all time.

Alongside early footage from the Maysles, the reels, filmed mostly by American artist Peter Beard, reveal Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis’s sister Lee Radziwill on camera defending kin Edith Bouvier Beale and daughter Edie against pressures from East Hampton, New York, authorities. Inside their decaying home, Little Edie sings her own rendition of the 1941 Louise Massey/Lee Penny tune “My Adobe Hacienda” and offers quotable gripes—such as “I’m always looking for my pants or my makeup”—that will make fans giggle and swoon.

With Radziwill mediating the relationship between camera and subject, the footage takes on a different tone than the sequences found in Grey Gardens. Big Edie and Little Edie seem like they are less on display, and their interactions appear to come from a more vulnerable (even desperate) place. And at times the film takes downright dark turns, offering details not captured in the Maysles Brothers’ film. An on-screen conversation hints at deeply hidden family secrets involving patriarch John “Black Jack” Bouvier, father of Kennedy Onassis and Radziwill. Asked about allegations of incest referred to in his movie, Olsson said that the footage in his film speaks for itself and explained that he has no more insight than is revealed in the rediscovered footage. Nevertheless, the references cast the Maysles film in a new light.

Producer Joslyn Barnes was at dinner with Peter and Nejma Beard, hosted by Susan Rockefeller a few years ago, when Beard revealed the existence of the Grey Gardens lost footage. Barnes called Olsson a few days later, having worked with him on previous films using archival footage, hoping to entice him to make a movie with the found reels.

“I’m trying not to label myself as an archivist filmmaker,” Olsson explained in Telluride last weekend. “It’s a detour from what I normally do but a wonderful detour.”

For That Summer, Olsson matched the lost Beale reels with Montauk footage filmed by Andy Warhol, Jonas Mekas, and Vincent Fremont. In the artsy beach community on the edge of Long Island, not far from the Beale’s beach house, Warhol’s superstars from the Factory are seen filming each other and lounging on the beach.

Olson equates the artists to the selfie-obsessed celebrities who today populate social-media platforms with photos and footage. “These characters are prototypes,” Olsson elaborated. “Everyone was filming everyone.”

Arthur Miller: Writer

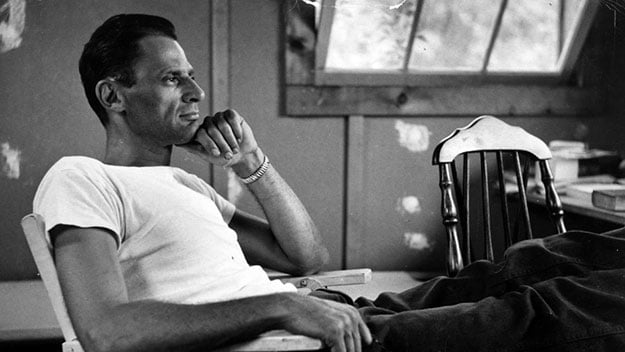

Filmmaker Rebecca Miller mined family and mass-media archives—including photos, home movies, texts, and news coverage—for her intimate portrait of her dad, the playwright and author Arthur Miller that debuted in Telluride last weekend.

Miller is seen, at various stages of his life, hanging out at a country house or engaging in projects in his woodworking shop. Using interviews from various times in her father’s life, Miller probes him about his battles with the U.S. government during the infamous Red Scare that targeted, among others, Hollywood screenwriters and authors, adds insights about paramour Marilyn Monroe, and reveals the toll of Miller’s battles with critics of his work over the years.

Like That Summer, Arthur Miller: Writer tackles a taboo subject from her family’s past, notably the discovery of a long-lost sibling, who is not seen in the movie. Rebecca Miller talks about the internal struggle of how to address the issues on camera. “I had an obligation to make this film,” she told Telluride audiences. “I feel like he belongs to you as much as my family.”

Land of the Free

Over five years ago, Danish filmmaker Camilla Magid, began attending support group meetings for those who are just out of prison in preparation for her mass-incarceration documentary Land of the Free, The film, which screened at Telluride, offers intimate looks at the lives of three people in South Central Los Angeles and reveals a composite sketch of someone trying to navigate life in American society in the wake of incarceration.

Where Ava DuVernay’s 13th and Eugene Jarecki’s The House I Live In examine the systemic and historical pattern of American racism at the root of its prison industrial complex, Magid’s empathetic film offers a humanistic examination that puts an individual face on the those trying to rebuild their lives after time in prison.

Magid doesn’t focus on her subjects’ crimes—some severe, some minor—but instead observes their reentry into a society that had forgotten them (and perhaps now would rather ignore them).

Just out of jail after nearly 20 years, a middle-aged African-American man savors his first cup of Starbucks coffee and learns just enough about the Internet to create a Gmail address. Harder to navigate are his interactions with others, from his fumbles as he searches to find a first girlfriend to his struggles as he tries to secure gainful employment despite his criminal record.

By exploring, in the words of the filmmaker, “the human catastrophe of mass incarceration,” Magid said in Telluride that she hoped, coming from Europe, to bring a new perspective to the topic. “As an outsider I wanted to focus on the more existential aspects to the issue of people who have committed a crime and who are trying to rebuild their lives,” Magid said. “The fact that these people who have served their time, they have no choice at all.”

Long Shot

Jacob LaMendola’s new documentary, Long Shot, which runs just under an hour, takes an equally incisive look at American social justice and does so with a similarly sensitive eye.

While searching IMDb for trivia about the TV series Curb Your Enthusiasm, LaMendola learned that creator and star Larry David (and his popular HBO show) played a key role in a recent murder trial. Juan Catalan, a young Southern Californian of color charged with the gang-style murder of a California teen maintained his innocence but evidence mounted against him and a police sketch inspired by eyewitness testimony implicated him in the gruesome crime.

As questions arose about the role of the LAPD, with its history of racial bias and abuse, the story took a dramatic turn when a trip to Dodger Stadium for a baseball game and surprising footage from the Larry David series were used in court to bring closure to the unsolved murder mystery.

In the film, LaMendola finds humanity and humor, as well as an emotional climax as the trial and the truth are revealed.

Human Flow

Chinese artist Ai Weiwei was a major presence over the weekend in Telluride. Prior to his trip to New York City to debut a new public art project, Ai Weiwei traveled to the festival just days after the Venice premiere of his new documentary, Human Flow.

A comprehensive look at the international migrant crisis, the exceptionally photographed film—mixing high-definition images, numerous drone shots, and even iPhone footage—looks at no fewer than 40 migrant camps in some 20 nations.

An artist who has worked in various formats (sculpture, video, photography), Berlin-based Ai Weiwei began exploring the vast impact of the international migrant crisis while vacationing with his son in Greece. As he learned more about the dramatic movements of people due to strife and threats to their livelihoods back home, he decided to meet, photograph, and document some of them.

After being unable to travel for many years due to detention by the Chinese government, Ai Weiwei regained his passport two years ago and began to dig deeper to learn more about an international crisis that has displaced as many as 65 million people around the world.

In Human Flow he visits refugees in Iraq, Greece, Bangladesh, Jordan, Pakistan, and along the U.S./Mexican border and documents the plight of countless migrants from Syria and Afghanistan. Their living conditions are shocking to witness. The film, made by activist production company Participant Media, incorporates stats about the crisis with never-before-seen footage inside the camps as well as interviews with experts.

“It started as a personal learning process to see where they come from and what different types of refugees are in the world,” Ai Weiwei detailed at Telluride. Cinematographer Christopher Doyle was among the roster of DPs that Ai Weiwei worked with to capture the people and conditions found in the camps around the world.

“It’s a struggle to film a situation like this,” the artist added, saying that he felt a growing sense of hopelessness as he filmed in migrant camps around the world. “You have to leave them, you can’t really help them that much and their conditions are so desperate you always have to pull yourself out,” he observed. “How much can we know about this situation and pretend it won’t affect our lives? In our civilized society how this can co-exist? I hope this film can bring some information and make people think about it.”

Darkest Hour

Even the highest-profile narrative films came from reality at Telluride this year.

Director Joe Wright and Gary Oldman, portraying a Trumpified Winston Churchill, swing for the fences in Darkest Hour, a look at British history during World War II that offers a compelling companion piece to Chris Nolan’s Dunkirk.

During the festival, producer Eric Fellner explained that he and producing partner Tim Bevan, of Working Time Films, had wanted to make a movie about Churchill for decades but could never find the way in. But then they gained insight into a small moment in history when Great Britain faced utter defeat prior to the Dunkirk evacuation with the support of vessels owned by local Brits.

For his part, Oldman said that he laughed when he was approached about portraying the iconic British leader. “Never go near it and never bring it up again,” he said to his advisors when they first brought up the role.

He came around, however, as he learned more about the intrigue unfolding inside 10 Downing Street as Churchill was appointed as prime minister and had to face the looming threats about to dramatically change the course of the war.

“My idea of Churchill was influenced, or contaminated, by other people who had played him,” Oldman said. But he finally agreed to take the role. “If you don’t risk, you don’t gain anything,” Oldman admitted.

Wright, who was sent the material last January, was drawn to Darkest Hour because he saw it as a story, in many ways, about indecision or a lack of certainty. “I make films from a very personal place,” Wright explained. “I made Pan and it had been utterly slated [i.e., criticized]. And I had doubts about myself,” he said. “In doubts you learn and grow. The only people I know who don’t have doubts are sociopaths.”