TCM Diary: The Town That Dreaded Sundown

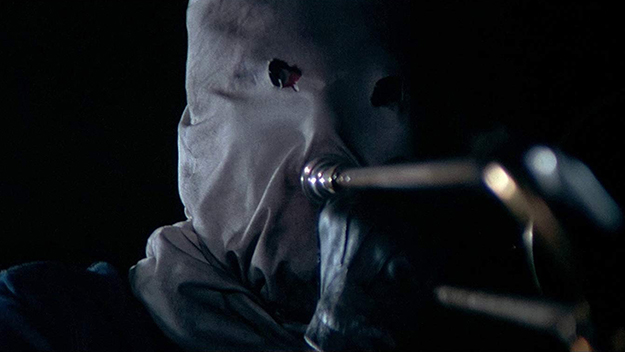

Images from The Town That Dreaded Sundown (Charles B. Pierce, 1976)

“The fact is, Chief,” Deputy Norman Ramsey tells his superior in The Town That Dreaded Sundown, “the only thing we really do know is, we’ve got a very strange person on our hands.” This report follows the first attack of a sadistic masked killer known as “The Phantom,” and “very strange person” proves to be a serious understatement. In Arkansas filmmaker Charles B. Pierce’s low-budget 1976 proto-slasher film—based on the unsolved 1946 Texarkana Moonlight Murders and their alleged perpetrator (dubbed “The Phantom Slayer”)—“serial killer” becomes most appropriate as the grisly events unfold in meticulous, gory detail.

Nearly 10 years prior, true crime had properly entered the American psyche anew with Truman Capote’s book In Cold Blood and Arthur Penn’s Bonnie and Clyde, which together presented readers and viewers with the shadowy details of criminal psychology and the shock of graphic violence. Although the names in The Town That Dreaded Sundown were changed from the actual events, the factual basis allowed for the most abject violence and terror to be portrayed on screen. In a canny approach to scaring his audience (and turning a profit), Pierce essentially offered stunned drive-in movie audiences with true crime dressed up as a horror film.

A pioneering American independent filmmaker, Pierce spent his formative years in Arkansas before moving to Texarkana. He produced his own homespun films, most of which featured some aspect of Southern life and its history (or a creative version thereof); in addition, he had worked as a set decorator on The Outlaw Josey Wales. Pierce spent a large part of his career outside of Hollywood before moving to Carmel, California in the early ’80s. There, he befriended Clint Eastwood, and the association led to the script for the 1983 Dirty Harry film Sudden Impact, and to Pierce writing and introducing the line “Go ahead, make my day” into the catch-phrase canon.

As a director, Pierce made his first splash by exploiting a much looser set of facts than those adapted in The Town That Dreaded Sundown. The frightening and oddly sentimental The Legend of Boggy Creek (1972) weaves together a smattering of “true” eyewitness accounts regarding the “skunk ape”—essentially, Bigfoot’s Arkansas-based cousin—through voiceover and re-creations of creature attacks on unwitting country folk. The unspoken motto behind Pierce’s most memorable and financially successful films appears to have been: “Truth is stranger than fiction, but even truth could use a little help.”

Pierce’s best-known films, however, are also united by a nostalgic, misty-eyed vision of the past. The Legend of Boggy Creek is as much an ode to the wonderment of Southern boyhood as it is a monster movie. Similarly, much of what makes The Town That Dreaded Sundown so disturbingly memorable is the tension between a wistful vision of apple-cheeked Americana and the faceless specter of death that threatens it. Images plucked from the Main Street of the American imagination—humble storefronts, movie marquees, barbershops, school dances—are imbued with a foreboding sense of impending violence. The darkness to which Pierce exposes his audience is not the metaphorical moral rot of Sinclair Lewis, but actual murder and death depicted in prolonged and starkly realistic scenes. Think Norman Rockwell’s Psycho or, perhaps, Ed Gein’s Our Town.

In one evocative scene in The Town That Dreaded Sundown, a young couple exits a movie theater in the rain as the narrator intones: “This is Howard W. Turner, age 29. Former CB who returned from overseas a few weeks ago. The young girl is Emma Lou Cook, and she is 17. They’ve been seeing each other for about six weeks. Emma Lou had dropped out of school in order to get a job and help out at home.” But what starts out with fatalistic Thornton Wilder tenderness quickly enters Friday the 13th territory when the couple is summarily stalked and killed by the sack-faced “Phantom.”

Pierce stokes the film’s dread by explicitly confronting the horror of such deviance existing in America’s heartland. Over a steak lunch, Texas Ranger Captain J.D. Morales (Ben Johnson) discusses the killer’s motivation with a criminal psychologist, who believes the killer will most likely not be caught. The doctor suggests that the Phantom could be any seemingly normal person, even one of the community’s most prominent citizens. As the two talk, a familiar pair of dirty boots, most likely the Phantom’s, are shown beneath a nearby table. Lawman and psychologist continue their lunch while the Phantom stands and coolly exits the restaurant undetected: both killer and lawman enjoy a good steak.

The most frightening and notorious sequence unfolds outside of town, where Pierce establishes a Hawthorne-esque wilderness of lonely fields, broken-down fences, and dusty country roads. In a scene that would feel at home in Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, a young woman, Peggy, performs with her trombone at the school dance. Before returning home, she and her boyfriend, Roy, stop in Lover’s Lane, an isolated spot in the woods. There the Phantom attacks, brutally beating Roy before shooting him, while Peggy meets with a death that would become the template for murder in the slasher films of the 1980s.

When Peggy attempts to escape, the Phantom sweeps her up in the same pseudo-romantic gesture Wolfmen and Frankensteins used to carry away their young victims. But in the violence that follows, the human body becomes a canvas for something sadistic, graphic, and maybe most terrifyingly, creative. The Phantom ties Peggy to a tree, then fastens his knife to the slide on her trombone. In a bizarre pantomime of sorts, the Phantom “plays” three notes on the instrument, sending the attached knife into Peggy’s back, killing her. It is a breathtaking nightmare of a scene with the kind of gonzo invention that earns the film the exploitation moniker.

Over the years, a parade of imitators have followed The Town That Dreaded Sundown, borrowing (and oftentimes outright stealing) from the film in large and small ways: the basic structural DNA of countless “slasher films” both good (Halloween) and bad (too many to list), not to mention the unkillable Jason Voorhees’ sack-clad visage in Friday the 13th Part 2. Yet Pierce’s film still holds an icy power over the viewer. Perhaps it’s because what lies at the heart of The Town That Dreaded Sundown is not only violence and death, but also fond remembrance of things lost.

Chris Shields is a New York–based filmmaker and writer. He is a frequent contributor to Art & Antiques magazine and Screen Slate.