TCM Diary: Robert Benchley

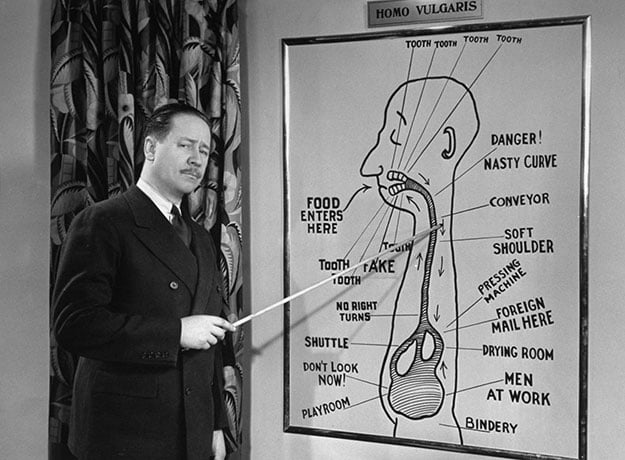

The Romance of Digestion

Now before we can discuss the humor of Robert Benchley, the first order of business is establishing who, or what, is a Robert Benchley. But before we do that, we should start with a brief précis on humor, because good manners dictate a movement from part to whole, and everyone knows you can take the humor out of the Benchley, but you can’t rout a Benchley from his humor. Or rather, everyone would know that if they understood the form of Benchley and the function of humor, which is the subject of our little talk here. No one knows the function of Benchley, least of all Benchley himself. Ahem.

This tangle of digressions and non sequiturs may not seem like much on paper, but humorist Robert Benchley (1889-1945) elevated them to ecstatic heights in a series of comic shorts, mostly eight to 10 minutes in length, in which he attempted to explain seemingly simple concepts while becoming hopelessly if affably muddled. Turner Classic Movies will air six of these “lectures” on September 5 between 6 and 7:30 in the morning. The efficacy of rising at that hour is covered by Professor Benchley in How to Sleep; the etiquette of same in How to Behave.

“I read everything he wrote when I was young,” Roger Ebert recalled, “and thought Benchley had to be the nicest, as well as the funniest, man alive.” Indeed, Benchley’s brand of wit was much gentler than those of his fellow scribes at New York’s legendary Algonquin Round Table (Dorothy Parker, George S. Kaufman, and Alexander Woollcott, to name three). Anyone familiar with the writings of Dave Barry will not be surprised to learn that Benchley is his idol: like the latter-day columnist, Benchley’s specialty was the struggle to maintain a foothold of sanity in a frenetic, increasingly competitive world. Rituals like eating a meal or reading a book take on harrowing dimensions in light of developments believed to make the processes more efficient (and invariably having the opposite effect). Sometimes it’s not changing protocol or technology but merely the need to do these things in front of others, offering advice and censure, that flummoxes “ordinary man” Benchley (a fairly relatable plight to those who, like the author, migrated to urban centers and had to keep pace with throngs of “modern” men and women who didn’t want to seem behind the times).

The Major and the Minor

He first honed this style in the pages of Vanity Fair, then in The New Yorker, to which he contributed regularly from 1925 to 1940; in hindsight it’s abundantly clear that Benchley was an architect of the latter publication’s aggrieved, oh-dear-what-now vein of humor (which continues to flourish in the snarky film reviews of Anthony Lane). Simultaneously it became evident that Benchley was as funny in person as he was on the page—ironic, since his cultivated persona was that of a poor public speaker defeated by stage fright and an unsteady grasp of his subject. His legendary “Treasurer’s Report,” which finds him grappling to explain a company’s annual earnings at a board meeting, began as a sketch for the 1922 Round Table revue No Sirree! and was filmed for Fox Movietone six years later—the first of nearly 50 short subjects headlined by Benchley in the 17 years before his death. It also appeared in slightly modified form as his character’s dinner speech in the 1943 Fred Astaire musical The Sky’s the Limit, a pleasant outing utterly stolen by Benchley. (His feature career found him playing mostly amiable bumblers, though in Billy Wilder’s directorial debut, The Major and the Minor, he invites a rain-drenched Ginger Rogers to slip out of her wet coat and into a dry martini.)

His claim to immortality is the succession of shorts which wed his inept orator with his beleaguered everyman (credited as “Joe”—or sometimes “Joseph A. Doakes”). Helmed by journeyman filmmakers like Arthur Ripley (who’d later make the Robert Mitchum cult classic Thunder Road) or Roy Rowland (director of the Dr. Seuss–scripted fantasia The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T), they typically begin with a composed and well-tailored Benchley seated behind a desk. On announcing the topic of his address (e.g., 1936’s How to Train a Dog, directed by Ripley), he immediately says something to betray his lack of authority or preparedness (“I don’t think I’m violating any confidences to say . . . that before you can train a dog, you have to get a dog”), chuckles nervously at the hole he’s dug himself, and continues digging. The lecture often serves as voice-over while B-roll of “Doakes” (also played by Benchley) demonstrates the futility of the advice being given; sometimes the speaker, on witnessing these outcomes, will modify or retract his guidance (“Actually, the best way to handle the whip is by throwing it away.”)

Much of the humor in the shorts derives from the sight of the dignified Benchley, with impeccably groomed mustache and elegant evening dress, forced to degrade himself before pets, children, waiters, and others whose respect he should command. (Think of him as Rodney Dangerfield in a tux.) Breaking the fourth wall is intrinsic to the lecture format, and the hapless instructor almost always ends up apologizing to the audience, often after losing his temper. Sometimes the obstructions to Doakes’s performance of simple tasks are bizarre; in How to Read (1938, Rowland), an attempt to distract himself in the dentist’s waiting room goes south when the only reading material at hand is a National Geographic-esque study of subtropical dental anomalies, leaving poor Doakes with frayed nerves and strained eyes. More often, though, it’s the nuisance of sharing overcrowded space with inconsiderate people; How to Behave (1936, Ripley) finds him at a dinner party where servants, newly arrived guests, and the telephone conspire to interrupt the story he was pressed to tell (but which everyone seems to have heard).

How to Sleep

Satirizing the soberly instructional “How-To” reels of the era, Benchley’s shorts—one of which, How to Sleep (1935, Nick Grinde), won an Academy Award—can be seen as proto-mockumentaries, sending up the nonfiction form half a century before Christopher Guest staked his career on the practice. The tone of Benchley’s narration hews closely to its object of parody, even as his words are patently absurd (such as a digression in 1938’s How to Raise a Baby, in which he contradicts the received wisdom that bath salts make children effete by suggesting that “if you have a good hearty specimen they shouldn’t do him any harm, and might even prevent him from becoming gloomy and morose”).

One of my favorite overlooked performances from the mid-’90s is Campbell Scott’s evocation of Benchley in Alan Rudolph’s Mrs. Parker and the Vicious Circle (named for Dorothy Parker and the Algonquin group’s nickname for their round-table-based antics). Though too young and slender to capture his physical essence, Scott nails the particular drollness of Benchley—even reenacting one of his shorts—and also the underlying sadness, stemming from Benchley’s belief that he had sold out his talents to Hollywood and (the film would have it) missed his chance at happiness with Parker, his equal in badinage. In Ebert’s review of the film, the critic notes that Benchley “was once as famous as he is now forgotten.” One hopes a rediscovery is imminent, for when it comes to sophisticated comedy, no one was ever better than Benchley at showing how it was done.

Robert Benchley’s comedy shorts air September 5 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.