TCM Diary: Myrna Loy’s Not Just Perfect

The Thin Man

It took 80 films for Myrna Loy to become an overnight star. The hardworking dancer-turned-actress weathered typecasting of one kind or another for years before sashaying into screen immortality, martini in hand, as Nora Charles in The Thin Man. Shot in just 12 days, W.S. “One-Take Woody” Van Dyke’s sparkling comic mystery became one of 1934’s biggest hits, and launched Hollywood’s first prestige franchise, founded on the unrivaled chemistry of its leading pair. Yet what’s most remarkable about the Thin Man series, at least until parenthood and the Hays Code thrust responsibility onto Nick and Nora, is how it depicts a long-standing marriage as neither a stifling domestic prison nor a fusty fortress of security, but as a madcap perpetual adventure, spiked with booze and banter and the occasional murder mystery to keep the magic alive. Simply put, William Powell and Myrna Loy were the first screen couple (and one might argue the last) to make marriage look like fun.

No less astonishing is the fact that Loy, a Montana rancher’s daughter named for a whistle-stop depot her father admired, should become, as her public-relations nickname would have it, “the perfect wife.” From the early looks of things, her career was headed in quite another direction.

Loy trained as a dancer and broke into film via small parts in musicals, including an unbilled role in the chorus of The Jazz Singer (1927). Her exotic features (accented by high-arched, pencil-thin eyebrows) and aloof yet seductive persona saw her typecast as temptresses, often of Asian heritage, in the unfortunate casting custom of the time. By the early 1930s she was making as many as a dozen films a year, with a typical role being that of Thirteen Women’s Ursula Georgi, a Eurasian femme fatale who enlists a clairvoyant to help engineer the deaths of the sorority sisters who’d once snubbed her. By the time she played Fah Lo See (“The whip! The whip!”), the malevolent daughter of Boris Karloff’s title character in The Mask of Fu Manchu, her fate as Foreign Villain appeared to be sealed.

Penthouse

Van Dyke saved her from what likely would’ve been a short-lived career, remembered only by protest groups and students of Edward Said. But before Nora came along, the director cast her in another pre-Code mystery with lightning-fast badinage, written by future Thin Man scribes (and real-life couple) Frances Goodrich and Albert Hackett. Penthouse, released by MGM in 1933, plays like a trial run of the amorous sleuthing scenario, but with a decidedly pre-Code flavor: the gumshoes are Jackson Durant (William Powell-ish Warner Baxter), a debonair criminal lawyer with friends in low places, and Gertie Waxted (Loy), a hostess in the employ of gangster Tony Gazotti (Nat Pendleton), who describes her as a girl who won’t squawk if you don’t ask her to breakfast. (“…Or if you do,” retorts Durant.)

The plot of Penthouse is needlessly complicated: Durant’s ex-lover’s fiancé is framed for the killing of his mistress by Gazotti’s gangland rival, who himself used to date the murder victim. (Got that?) The first half-hour is all table-setting, redeemed by the witty Goodrich-Hackett dialogue and genre tropes that can only be called charming—e.g., the tongue-clucking butler who takes a blow to the head in stride, played to wry perfection by Charles Butterworth. (The fact that racketeer-mouthpiece comedies were a genre—almost as fertile as jewel thief romances—is enough to prompt a nostalgic grin.) The movie proper begins with the belated introduction of Gertie, descending a flight of stairs at Tony’s nightclub, cloaked in a black-and-white gown. Loy’s repartee with Baxter is electric, making apparent why, as relayed in her memoirs, director Van Dyke proclaimed in the MGM commissary to all in earshot, “This girl’s going to be a big star! Next year she’ll be a star!”

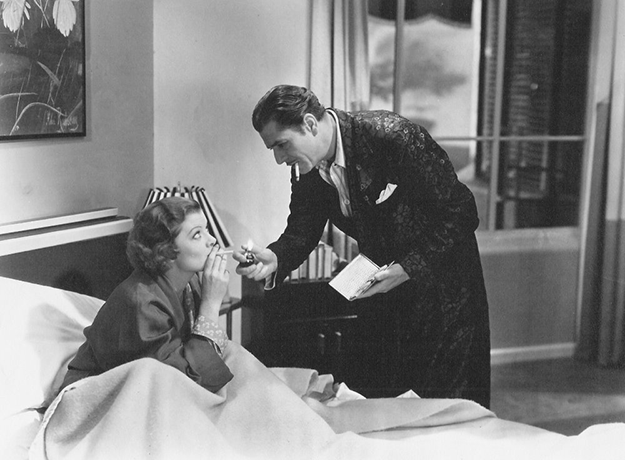

Durant invites Gertie back to his opulent Art Deco pad to help solve the killing of her friend and exonerate the accused. Over 1930s movie breakfasts—the kind where someone daintily prods a grapefruit half while orchards-worth of fruit go unattended—she recalls trifling details that steer his investigation. Gertie, Durant, and his butler form a domestic arrangement so warm and cozy as to suggest that the formula for the ideal nuclear family is fixer, call girl, and manservant. With all due praise to the dashing and immensely appealing Baxter, most of the credit goes to Loy. Her refined but fluttery voice (which served her well as Billie Burke in The Great Ziegfeld) belies a saucy disposition and an unerring verbal backhand. Chiding the single-minded Durant’s outward indifference to her charms (“A few more weeks of this and I’ll be out of condition”) and even acting as wingwoman when his ex drops by unannounced, Loy’s Gertie is much more than a love object—she’s a friend, a playmate and a soulmate.

The Animal Kingdom

Like Rear Window and the collected works of Howard Hawks, Penthouse is one of those films where the heroine is undervalued by the hero until she gets involved in his quest and proves her mettle under fire. Though it prudently never regards her as a “fallen woman,” the screenplay is scant with the details of Gertie’s life—but Loy provides valuable clues. Giving her the faintest upper-crust mannerisms, plainly artificial, Loy sketches a good-hearted gal striving to bring class to a common trade. You find yourself passing the time in overplotted scenes by conjuring narratives about Gertie: aspiring model or chorus girl, divested of illusions but not of compassion. When, dropping her guard, she reveals to Durant that his life means more to her than her own, every beating heart suddenly melts, including his. One is hard-pressed to cite a more tender scene in Golden Age cinema than the one in which she leans in the entrance to his foyer, calling his apartment “home” as he kisses her forearm. Finding mirth and poignancy in the same moment, Loy announces her arrival as a sincere actress and a redoubtable star.

A strong indicator of bona fide stardom is the ability to play a role against type, neither likeable nor the lead, and still manage to steal the show. That’s the feat Loy achieves in The Animal Kingdom, a 1932 adaptation of Philip Barry’s sophisticated stage play. Helmed by Edward H. Griffith, who’d directed Loy in another pre-Code marital roundelay, Rebound (1931), The Animal Kingdom casts her as Cecelia “Cee” Collier. Cee’s husband, publisher Tom (Leslie Howard), had been maintaining a no-strings live-in arrangement with his lover Daisy (Ann Harding) that of late had scandalized his family. While Daisy and Tom (unlike their Fitzgeraldian namesakes, the Buchanans) were always candid and obliging of one another, Cee seeks to reform her errant husband, using all manner of guile to convert him to her middle-class values.

That is to say, Harding has the typical Loy role—the common-law wife who makes no demands and imparts no grief—and Loy’s character is, on paper, a calculating, castrating shrew. In the film’s most excruciating scene, Cee manipulates Tom into firing his rough-hewn butler, a prizefighter down on his luck (William Gargan), by claiming he’s costing his friend the chance to reach his full potential by keeping him around as a servant—an arrangement that had been wholly satisfying to all parties until Cee’s arrival. Before long she has Tom hosting soirees for society snobs he once held in contempt, and publishing lucrative but artistically bankrupt manuscripts. Daisy cautions him against becoming “a little cog in the big machinery,” but her earnest entreaties are a poor match for Cee’s upturned nose, selective headaches, and silk negligee.

Lonelyhearts

In other hands, the role of Cee would be thankless, perhaps even unplayable, but Loy makes her stealthily alluring. Her wily intelligence (she’s not merely sexy, but knowing in her sexuality) and theatrical gestures (“You dah-ling!” she enthuses) make her sprightly even when scheming. It’s easy to see how Tom and others could lose their heads over her—all the while she’s perpetrating her mischief, she’s too charismatic and clever to dismiss, and Harding’s “free as air” lover carries more than a whiff of sanctimony. Cee Collier was the first of many imperfect wives Loy would play in her versatile career, culminating with embittered spouse roles in Lonelyhearts and From the Terrace (the latter a brilliant turn as a self-pitying lush). But like all of her personages, Cee is sharply drawn. She encourages Tom to drink more champagne to make everything “so lovely and vague—the way I feel right now,” but there’s nothing vague in the precise, confident, and lovely screen figure of Myrna Loy.

The Jazz Singer airs December 5; Penthouse, The Animal Kingdom, Thirteen Women and The Mask of Fu Manchu December 9, and Thin Man and The Great Ziegfeld December 23 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.