TCM Diary: Desert Warfare

The Lost Patrol

Lawrence of Arabia, at least in David Lean’s interpretation, favored the desert because he found it clean. The titular corps of John Ford’s The Lost Patrol had a harsher take on their arid surroundings, summed up in the film’s florid opening titles: it “seemed on fire with the sun” and “wore the blank look of death.” The desert, like the sea or outer space, is boundless in its opacity and sprawl, thus it can be at once ablaze and immaculate, and films about desert warfare—several of which are spotlighted in TCM’s “Summer Under the Stars”—suggest a parched ocean of unfathomable secrets and terrifying grandeur.

The Lost Patrol are a dozen WWI-era British troops stranded in the Mesopotamian wilderness when their senior officer is killed before he can share the facts of their mission. The sergeant (Victor McLaglen) who is elevated to command resolves to rejoin the regiment wherever it may be, requiring that they fend off heatstroke, exhaustion, fear of unseen snipers, and the effect of uncertainty on the human psyche which the men call “going bughouse.” (Some are already halfway there: Boris Karloff’s religious zealot Sanders, who insists Mesopotamia was once the garden of Eden, quivers over scripture about fruitful lands turned to desert “for the wickedness of them that dwell therein.”) One by one, the men succumb to the hazards of the wasteland, or to bullets from an enemy force likened to a relentless ghost. Each casualty is reported with unsparing, pre-Code explicitness (“Right through the head!” is the verdict for a lookout shot down from a palm tree). Soon the company has dwindled to a mere handful.

The dunes that burned orange in Lawrence of Arabia take on a blinding sheen in Harold Wenstrom’s black-and-white photography, with Yuma, Arizona filling in for what is now Iraq. The sweltering heat is palpable as the bone-weary soldiers stagger through the remote expanse; perhaps only Hiroshi Teshigahara’s Woman in the Dunes offers a starker achromatic view of an infinite sand-swept prison. Ford is attuned to the topography of his environment—to the mountainous ridges and rambling valleys of sand, and to the concavity of each footprint in the unsullied ground. Max Steiner’s aptly militaristic score, featuring regimental bagpipes and sampling WWI marching songs “Pack Up Your Troubles in Your Old Kit-Bag” and “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” mirrors the infantrymen’s trudge with its relentless beat.

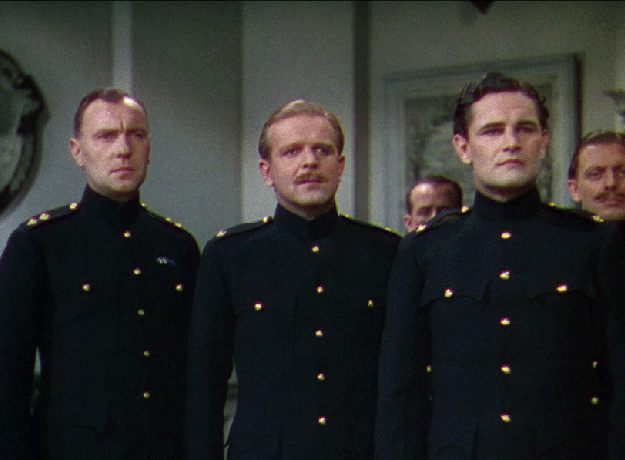

The Lost Patrol

Made in 1934, The Lost Patrol presages Stagecoach and so many of Ford’s later westerns in its focus on a steadfast but outmatched crew, varying in age, experience, and disposition, endangered by hostile surroundings, Other-ized adversaries, and instability within their ranks. As he did frequently, Ford varies between nonverbal sequences of visual majesty and dialogue scenes, often consisting of macho digressions (past drinking exploits, etc.) and appreciation of life’s simple sensory pleasures. He even works in some of his patented comedy of camaraderie, as a career soldier with 27 years’ experience taunts a cohort with just 25—until the latter points out the three of the former’s were spent in the guardhouse. No one was better than Ford at divesting stock characters of their mothballs and rendering them both archetypal and authentic, and that’s especially true here.

When you think of Ford, you think automatically of Victor McLaglen. Perhaps not in the same rush of memory as John Wayne or Henry Fonda, and as likely as not without recall of his name. But the burly onetime bare-knuckle boxer and WWI veteran (who’d served with the Irish Fusiliers near the time and place of the film’s setting) teamed with Ford on a dozen features; both men won Oscars for their next collaboration, The Informer. Often a comic foil in later years, his oxlike frame and roughhouse manner culpable for many an on-screen donnybrook, McLaglen had the bluff confidence and character-rich voice that many early sound stars lacked. He’s superb here as the stoic, even-keeled acting commander, taking a fatherly interest in his men and concealing his fears for their sake. Late in the day he shares touching details about his civilian life, and when at last he, too, starts to come undone it feels most convincing. (McLaglen’s brother Cyril had played the same role in a 1929 silent treatment of this story.)

Karloff, looking gaunt and stricken from the trial of reconciling Sanders’s deep faith with the senseless killing in which he’s forced to participate, is finally granted a sizable speaking part after embodying Frankenstein’s monster and the mummy Imhotep. His mellow, cultured voice may be used for more than grunts, but Sanders falls in line with the others in that he’s forced to confront his creator—to try and make sense of circumstances that defy reason, and decry having consciousness if it merely serves to torment him. When another soldier affirms his secular faith in good wine, comfortable shoes, and the staples of a contented English life, Sanders can only recoil at his omission of all things divine. Among the waylaid patrol, he is in every sense the most lost.

The Four Feathers

Alienation is also the fate of Harry Faversham (John Clements) in The Four Feathers, a 1939 adaptation of A.E.W. Mason’s oft-filmed novel, directed by Zoltán Korda and produced by his brother Alexander (with a third sibling, Vincent, designing the sets). The son of a bellicose Crimean War veteran, Harry was weaned on rhetoric about duty and tradition, forced to listen as his father and his aging fellow legionnaires tell and retell their war stories. One of them, played by character actor C. Aubrey Smith—so tall and unassailably English that a co-star once likened him to a cricket bat—likes to recount battlefield triumphs with the aid of nuts and fruit. (“And here,” he says, positioning the pineapple in the center of the action, “was I!”)

On his 15th birthday, the geriatric warriors relate to Harry the story of a soldier too paralyzed with fright to deliver a message in battle, later hounded into suicide (which all present agree was the only manful course of action). Harry joins a regiment out of fealty, but on the eve of deployment to the Sudan to fight in the Mahdist War, he resigns his commission. As a result he is gifted white feathers of cowardice by his three childhood friends, now soldiers all, and plucks a fourth from his fiancée’s fan when she fails to support his decision.

The bulk of the film comprises Harry’s journey into the Sudan, disguised as a branded member of the mute Sangali tribe, to prove his courage and return the feathers. Meanwhile his romantic rival John Durrance (Ralph Richardson), now a Captain in the army, is blinded by exposure to the blistering sun and left for dead on the battlefield. The scenes where Richardson stumbles down a rocky crag to retrieve his shade-providing cap, heat rippling through the air in a woozy POV shot, and later where he frantically strikes match after match as the reality of his blindness sets in, are among the most viscerally terrifying in all cinema.

The Four Feathers

The Four Feathers was made at the dawn of the Second World War; many Hollywood films would cover that conflict’s North African campaign (including Billy Wilder’s Five Graves to Cairo and Korda’s own Sahara, a reworking of The Lost Patrol), but Four Feathers was filmed on location in the Sudan, featuring extras who’d borne witness to the events as they had occurred four decades earlier. Accordingly, it has the sweep of an epic unhindered by soundstages; the scope and simultaneous action of its battle sequences rival those of Lawrence of Arabia, which its rousingly scored scenes of men astride camels constantly foreshadows.

If The Lost Patrol depicts the power of the desert to shatter the minds and wills of brave men, The Four Feathers posits it as a place of redemption for the disgraced and enlightenment for the metaphorically blind. At the start, Richardson’s Durrance perceives only honor and heroism, and can’t comprehend a reason for disavowal of duty beyond rank cowardice. In losing his sight it is he, not the tenacious Harry, who considers suicide—but by the end his eyes are opened, as it were. For Harry, the desert has an almost Biblical purifying effect. More than anyone this side of T.E. Lawrence, he comes to understand that what is clean to the eye is also cleansing to the soul.

The Lost Patrol airs August 26 and The Four Feathers on August 13 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.