TCM Diary: David and Lisa

To best understand the simple, timeless power of Frank Perry’s David and Lisa, it’s necessary to consider the pitfalls it avoids. Arriving in 1962, well into Hollywood’s postwar fascination with psychiatric disorders (expressed in Spellbound, The Snake Pit, The Three Faces of Eve, and Psycho), the low-budget indie eschews surface gloss and star-powered heroics. Moreover, in its depiction of the evolving friendship between two young patients in a mental institution—David played by Keir Dullea and Lisa by Janet Margolin—it resists every invitation to bathos, refusing to ennoble the afflicted pair or present their association as curative. Adapted by Perry’s wife Eleanor from a case history by Theodore Isaac Rubin, it regards psychiatrists not as highbrow Freud clones whose insights surpass comprehension, but as dedicated professionals imperfectly breaking down barriers to connect with their patients. Notably, the plainspoken head physician (Howard Da Silva) makes a point to avoid jargon; only the well-read but supercilious David uses it, in a way the film presents derisively. And while flawed parenting is evident (where is it not?), the Perrys break with convention by not blaming everything on Mom and Dad or positing that remembrance of inciting episodes will bring about instant recovery. For David and Lisa, healing is gradual, nonlinear, and far from guaranteed.

To its immense credit, Eleanor Perry’s screenplay declines to label David and Lisa but opts merely to portray their symptoms. David can’t bear to be touched by anyone and exhibits a preoccupation with time, fixating on stopped clocks and yearning for a mechanism that constantly tells him the hour—even though he believes “time is cutting off our heads minute by minute,” a figure of speech that’s literalized in dreams in which he decapitates acquaintances with the hands of a giant clock. Lisa, meanwhile, speaks entirely in rhyme (“I’m a pearl of a girl”), and manifests a second personality, called Muriel, who doesn’t speak at all. By rhyming along with her and sparing her the condescension he shows everyone else, David becomes Lisa’s confidant (as the doctors were unable to do) and later her friend.

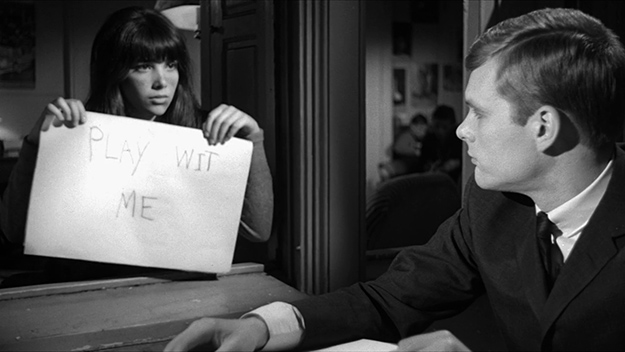

Unlike its cinematic forerunners which galvanize sympathy for their aggrieved protagonists (The Snake Pit’s Olivia de Havilland, The Three Faces of Eve’s Joanne Woodward), David and Lisa permits the titular duo to be difficult cases in every sense. David is stiff, clipped, and deliberately rude, especially to Da Silva’s Dr. Swinford, of whose fraudulence he is convinced. He defines himself by the many things he abhors: clubs, exercise, music, and all of the facility’s means of socialization. “Let’s say if I feel like talking to you, I’ll talk to you” is a typical pronouncement. Lisa, resolutely childlike, comes at David with a handmade sign that reads “PLAY WIT ME” [sic], and resents his attention to others on the premises. Both in their own ways are obsessed with maintaining control.

However pedantic he may be, David’s instincts are assured (except with regard to Dr. Swinford). His assertion that rhyming is Lisa’s attempt to protect her own personality from usurpation by Muriel is most astute, and his advice to Swinford (whom he comes to trust) that “a more permissive approach” will bring her out of her shell belies the widely held view that he lacks empathy. Likewise, he is alert to the tendency of Swinford (out of kindness) and his mother (out of willful self-delusion) to characterize the treatment center’s neurotic residents as “they,” exempting David from their ranks. “I’m a real compulsive nut!” he declares, wholeheartedly accepting his diagnosis and forging a kinship with the others. (The film’s most affecting scene finds a group of them on an excursion, chanting “Bunch of screwballs! Spoiling the town!” at an insensitive man who described them as such to his family, cementing their solidarity and refusal to be victimized.)

The screenplay’s key affirmation, placing it well ahead of its time, is the ability of opposing forces to harmonize in nature or in one’s personality, signaled early in the film by Dr. Swinford’s conviction that people can love and hate at the same time. David recalls being frightened in his youth by a circus freak named George Georgina, who sported a beard on one side of his face and a breast on the other side of her torso. The idea of someone so non-binary, so unclassifiable, jostled David’s belief in a world of absolutes. Though the film offers no epiphanies or tidy catharses, by the end David believes the sight of George Georgina would no longer disturb him. Lisa’s recognition that David was mean to her out of kindness to a fellow patient whose piano recital she interrupted presages her acknowledgment that “Lisa” and “Muriel” can find a balance within her (she subsequently signs a drawing “Muriel & Lisa”). The notion that dualities can coexist defies the boilerplate belief, common in such films, that one impulse or persona must survive at the expense of the other.

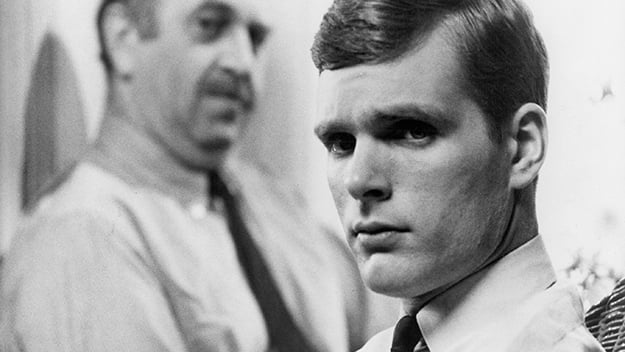

For all its maturity and wisdom, David and Lisa marked Frank and Eleanor Perry’s feature debut; both were nominated for Academy Awards. They collaborated on five more films over the next eight years, distinguished by their sensitivity to both the anxieties of a restless age and the universal truths of human nature. (A case could be made for the supremacy of any of them; I’d give the slightest edge to 1969’s Last Summer, a shattering study of teenage cruelty and innocence lost.) The stars of David and Lisa were similarly untested: Margolin, who would appear as Woody Allen’s status-obsessed wife in Annie Hall, had never acted before and brought a doll to her audition. Dullea, later the lead astronaut Dave in 2001: A Space Odyssey, had surfaced in a handful of TV shows and just one prior feature, The Hoodlum Priest. The only veteran on set was Da Silva, a ubiquitous heavy throughout the ’40s whose film career stalled for over a decade when he was blacklisted by the House Un-American Activities Committee. Dr. Swinford was his first big-screen appearance since 1951, and his delicately understated turn is the jewel in the film’s crown, radiating reassurance and practicality in equal measure. (This comeback role brought him steady employment for the next quarter-century, playing real-life personages ranging from Benjamin Franklin in the musical 1776 to Louis B. Mayer in Frank Perry’s cult classic Mommie Dearest.)

In measuring David and Lisa by the snares it perspicaciously evades, above all is the heroic fact that it never becomes an ode to the healing power of love. The touch-averse David and the infantilized Lisa neither fall into a romance nor emerge fully recovered, but if they’re closer to wellness in the end it’s because of their credible shared understanding. When you run away from something, David posits, you’re also running toward something. In moving haltingly toward each other, David and Lisa pull away from isolation and stagnation, and cease to view themselves as clocks frozen in time.

David and Lisa will air Tuesday, November 28 on Turner Classic Movies.

Steven Mears received his MA in film from Columbia University, where he wrote a thesis on depictions of old age in American cinema.