Talking Pictures: Mani Ratnam’s PS1

This article appeared in the November 3, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

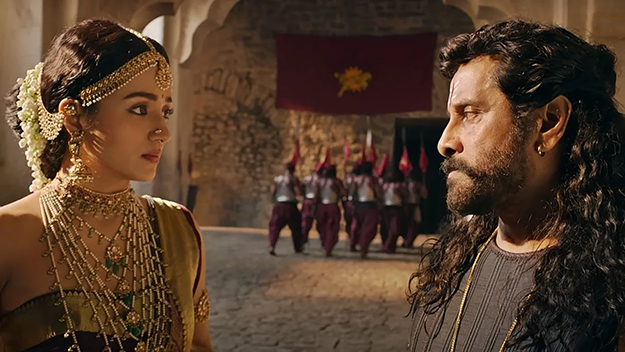

Ponniyin Selvan: I (Mani Ratnam, 2022)

Ponniyin Selvan: I, or PS1, the first installment in Indian filmmaker Mani Ratnam’s two-part historical epic, has reportedly become the highest-grossing Tamil-language movie of all time in the United States. This success follows the dithyrambic stateside reception of S.S. Rajamouli’s Telugu picture RRR (2022), and together they seem to have unveiled, to many cinephiles, a whole new realm in the cinemas of Southern India. Besides their geographical origin, RRR and PS1 have the commonality of being works of their time—projects whose colossal ambitions were made material by the availability of bigger budgets, affordable VFX, simultaneous international distribution, and digital marketing riding on India’s telecom boom.

PS1 is Mani Ratnam’s first literary adaptation and his third period picture, following Nayakan (1987) and Iruvar (1997), which are arguably his two finest films. A reverent retelling of “Kalki” Krishnamurthy’s beloved 1955 novel of the same name, PS1 zeroes in on a moment of political crisis in the medieval Chola empire, which ruled over South India from c. 848 AD to 1279 AD. Here, as dissident ministers plot to overthrow the ailing 10th-century Emperor Sundara Chozhar, Princess Kundavai (Trisha) seeks to alert her brothers, Crown Prince Aditha Karikalan (Vikram) and the younger Arulmozhi Varman (Jayam Ravi), both waging expansionist wars far from the throne. These royal scions, seemingly modeled on the three levels of the psyche, are linked by the ethereal, enigmatic Nandini (Aishwarya Rai Bachchan), Karikalan’s former lover and the wife of one of the conspirators, and Vanthiyathevan (Karthi), the chivalrous messenger through whose eyes we discover the story.

Though RRR and PS1 are both opulent period pieces featuring multiple stars, the two films diverge starkly in tone and texture. Where Rajamouli’s film worked a simple, trope-driven narrative—two men on separate espionage missions during the Indian independence movement—into an expressive, crowd-pleasing tale of unified struggle in the face of colonial rule, PS1 is a knotty affair that ties its five leads to each other in every combination, enmeshing them in a thick web of spies, conspirators, assassins, and allies. Fevered plot mechanics take precedence over both eye-popping action sequences and character development. Even so, DP Ravi Varman’s camera is able to linger on telling details such as Nandini’s disarming bare nape or a twinkle of liberated ambition in the eyes of Vanthiyathevan.

While recent historical productions in India—like Manikarnika: The Queen of Jhansi (2019) or Tanhaji: The Unsung Warrior (2020), or even RRR, to name a few—have been occasions to construct a glorious national lineage or project present-day communal anxieties onto the past, PS1 refuses to stoke identitarian claims of any kind. The film doesn’t play up its characters’ linguistic or religious affiliations, and it eschews broad, historiographic context in favor of the Byzantine machinations of court intrigue. Ratnam has never been one to play to the political gallery: his Renoir-like humanism trumps polemics or partisanship. All this makes PS1 something of an exception in a movie industry and culture currently gripped by demagoguery and opportunism.

In its verbosity and narrative density, PS1 is an unusual work for Mani Ratnam. But it is characteristic of this filmmaker to ground material that lends itself to every kind of extravagance in a plausible, could-have-been reality. Verisimilitude is a value he often invokes in his interviews, and the gestures, behaviors, actions, and emotions of his films are all shaped to ring true in the internal logic of their worlds. The sense of irony one might expect to bring to other popular Indian fare such as RRR is unneeded here.

For almost 40 years now, Ratnam has been making “respectable” commercial films that, in public opinion, have distinguished themselves from the formulaic “silliness” of contemporary mainstream productions. Part of the reputation of these works derives from their sophisticated polish, flawlessly wrought by a team of top technical talent, many of whom are recurrent collaborators, like composer A.R. Rahman (on 17 films) and editor A. Sreekar Prasad (12). This synergy has also ensured the allegiance of leading acting talents such as Vikram and Rai Bachchan, who attach a high value to appearing in the films of “Mani sir,” even when they have to play second fiddle or share screen space with other stars.

But the renown is equally a matter of a distinct directorial sensibility. Whether crime sagas or tortured romances, family dramas or political fables, Ratnam’s films are marked by an understated realism in their writing and acting, an intimacy in relationships, and an absence of glib moralism. There are barely any villains in his cinema, only conflicting perspectives; even the terrorists of the kidnapping drama Roja (1992) or the henchman antihero of the political thriller Yuva (2004) are given believable, if not condonable, reasons for what they do. A Mani Ratnam feature is also recognizable in its cosmopolitanism, complex female characters, sardonic domestic interactions, unexpected casting, individuation of crowds, subtly shifting focal points, and sarcastic lovers exchanging teasing witticisms in loud voices.

To overstate his singularity, however, runs the risk of misunderstanding his work, which is firmly rooted in the mainstream filmmaking traditions of his country. Ratnam is not a radical or an independent; he has never felt the need to break away completely from the precepts of popular film practice. Such derided elements as the song sequence, the comic track, and the mid-film interval are to him aesthetic givens to be creatively handled, not hindrances to be done away with. His works are preeminent sites for tracing the dialectic between convention and innovation that characterizes the evolution of Indian cinema at large; for instance, where an emphatic victory ballad like “Chola Chola” would have served as an escapist break from the narrative in a more standard film, in PS1, the song is used to shift emotional gears, segueing from a bitter lament of lost love to a revelation of a repressed trauma.

Throughout his four-decade career, Ratnam has been gnawing away at the boundaries of Indian mainstream filmmaking from within, his innovations having been adopted by subsequent directors and, in turn, rendered into conventions. It is hard to watch a movie meet-cute without being reminded of similar scenes from Ratnam’s Alai Payuthey (2000), where would-be valentines trade one-upping wisecracks at a friend’s wedding, or from Mouna Ragam (1986) or Bombay (1995). Certainly, one source of this astounding longevity is the filmmaker’s constant effort to be in tune with his times. Be it cross-border terrorism or communal riots, civil wars or insurgency, the hot-button topics of Indian politics have regularly made their way into his films. But it is in the modest facets of everyday life that Ratnam’s cinema has remained most contemporary, even occasionally showing signs of things to come. From the interrogation of arranged marriages in Mouna Ragam to the normalization of live-in relationships in O Kadhal Kanmani (2015); from a career-long dedication to portraying nontraditional models of masculinity and casting striking faces in bit parts, to the use of real public transport and everyday locations, Ratnam’s films have long been characterized by an insistence on responding to the world and the times that engender them.

In his book Conversations with Mani Ratnam (2012), Baradwaj Rangan recalls how, with the arrival of this young rebel in the ’80s, the rest of Tamil cinema suddenly seemed to have gotten older. “Most filmmakers, then, were adults who’d left their youth far behind, and their portrayals of the young harked back to their times,” writes the critic. “Mani Ratnam, on the other hand, seemed to be one of us… he seemed to completely get us.” Whether young viewers of today feel the same about this director remains to be seen, but even PS1, for all its period stylings, registers as a contemporary work: in the gestures of a medieval swordsman making a pass at a boatwoman on a catamaran, one cannot but sense the everyday passions of an urban lad trying his luck with a young woman on a train in 2022.

Srikanth Srinivasan is a film critic from Bangalore, India, and the author of Modernism by Other Means: The Films of Amit Dutta (2021, Lightcube).