Space Ways: 2023 Cosmic Rays Film Festival

This article appeared in the April 6, 2023 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

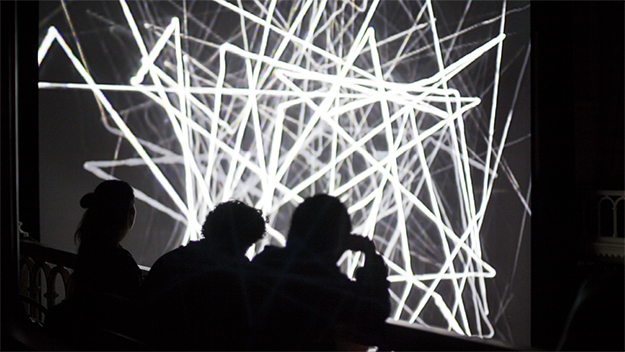

Performance view of ΔV/ΔT (Jonas Bers, 2023). Courtesy of the artist.

In the discourse about the pandemic’s effects on moviegoing and the latest death of cinema, there has been scarcely any mention of the plight of emphatically noncommercial modes like experimental film and video or artists’ cinema. The very terms, after all, suggest that no good capitalist should care: why wring one’s hands over the fate of cinema at the margins, whose makers aren’t even trying to secure Netflix deals? But in fact, artists’ cinema has been enjoying something of a resurgence. Recent years have seen a host of new online initiatives, from e-flux’s video platform and the Prismatic Ground film festival to niche meme accounts, which provide access to objects once largely inaccessible to the general public. Meanwhile, there’s a growing hunger for cinematic experiences that resist compatibility with digitization and internet exhibition, meaning that experimental film screenings routinely sell out at museums and microcinemas alike.

The small, regional experimental film festival—the classical site for alternative film exhibition since the mid-century avant-garde period—in particular seems to have emerged stronger from the pandemic. Over a spring weekend this past month, the itinerant American cinephile had the luxury of deciding between three simultaneous showcases in disparate corners of the country: Onion City Experimental Film Festival in Chicago; Light Field in San Francisco; and the Cosmic Rays Film Festival in Chapel Hill, North Carolina. The last of these, curated by artist-filmmakers Sabine Gruffat and Bill Brown, launched in 2018, and is a relative newcomer. Realheads will note that the festival’s name is a nod to the 1962 Bruce Conner film Cosmic Ray—a lysergic paean to Ray Charles and a prime example of Conner’s high-octane montage. But as a university-centered festival that cultivates both a regional and an international network of filmmakers, curators, cinephiles, and critics, Cosmic Rays also gestures, with its name, to more plainly scientific associations, like the atmospheric disruptions from space that bridge planes of wildly divergent scales. Its reach is interstellar and terrestrial, global and local.

On opening night, Cosmic Rays offered a selection of three live projection performances, staged at a concert venue named Cat’s Cradle. Ephemeral, abstract, and often very, very loud, these sets afforded a look under the hood of a wide spectrum of analog and digital technologies, which the performers hacked and manipulated in real time. Tomonari Nishikawa’s Six Seventy-Two Variations (an earlier iteration of which the artist performed in the Currents section of the New York Film Festival in 2021) was the most minimalist of the three, consisting of a projection of a loop of clear 16mm leader, to which Nishikawa added a steady accumulation of scratches. As the performance unfolded and the artist’s jagged engravings filled the frame, the projector’s optical sound sensors registered them as awkward ka-chunks which gradually coalesced into a pulsating off-rhythm. At the other technological extreme was Jon Satrom’s dizzying and frequently hilarious screen-share performance, Prepared Desktop, in which the artist ran simple scripts to exploit the basics of the Mac OS interface—including many of its familiar functions, alert sounds, and text-to-speech voices—in subtle, then wildly maximalist ways. Somewhere in the fuzzy middle of the analog-digital divide, Jonas Bers’s ΔV/ΔT—named for the acceleration formula—made use of an oscilloscope, two video mixers, and a mad scientist’s bank of knobs and wires. Bers sculpted waveforms into undulating monochrome blobs to produce an electronic cacophony, conjuring a sense of (controlled) danger as he explored the thrilling polarities of signal and noise.

The core of the festival lay in its four programs of short films—none of which, in accordance with submission guidelines, exceeded 15 minutes. Like the live sets, many of these works saw their makers exploring a range of media technologies and the ways in which they shape their subjects, be they human and animal bodies, urban and natural spaces, or history and politics. This approach was clearly evidenced by the festival’s sole single-artist program, devoted to a trilogy of recent films by Suneil Sanzgiri. Collectively dubbed Barobar Jagtana, the suite investigates past and present liberation movements of India—in Goa, Kashmir, and the diaspora—and traces their transnational reverberations. Sanzgiri exploits cinema’s ability to reconstruct time and space nonlinearly with an arsenal of techniques—analog film and desktop interfaces, oral history and poetry, animation and drone footage—to unsettle our geographic and historical orientations and gesture at new solidarities.

Elsewhere, Nicolas Gebbe’s (perhaps too obviously titled) Lockdown Dreamscape deploys photogrammetry to stitch pictures of his apartment into a seemingly endless digital maze, a synthetic long take that winds through the oozing architecture and deliriously mutable bric-a-brac of his home. Similarly, Kelly Sears’s Phase II uses collaged photos of city skylines alongside voiceover narration to relate a speculative fiction about gentrification and urban control in a near-future Denver. Sears’s subtle blend of science fiction, street photography, and animation techniques anticipates the dystopian world-building of real estate, constructing a cityscape where loudspeakers sprout on poles like malevolent flowers alongside proliferating condo buildings, enacting sonic warfare on local populations in the name of endless development.

Film editing is itself a kind of technology for the construction of new spaces, temporalities, and modes of consciousness. True to the festival’s namesake, several films screened there employed found-footage aesthetics in the lineage of Conner, albeit with an emphasis on the oneiric, dissociative assemblages of his later works like Take the 5:10 to Dreamland (1976) and Valse triste (1977). Among the best of these, Alina Taalman’s Prearranged Signal interweaves a rich catalog of images and sounds, cutting from 16mm footage of vegetation and rippling seas to scenes of lonely women and suburban homes from old movies. Amid a soundtrack of sinister electronic noise and droning field recordings of nature, a voice asks, “Do you know what the signal is?” Taalman’s film stages the act of interpretation itself—that alternately uneasy and thrilling task of locating meaning within a roiling ocean of media sensations. Prearranged Signal, which opened the final program of the festival, felt in harmony with Cosmic Rays’s curatorial remit: an invitation to draw unexpected connections across technologies, beyond genres, and between images.

Leo Goldsmith is a Visiting Assistant Professor of Culture and Media at Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, The New School, and a programming advisor for the New York Film Festival.