Screen Time: Takahiko Iimura (1937-2022)

This article appeared in the September 8, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

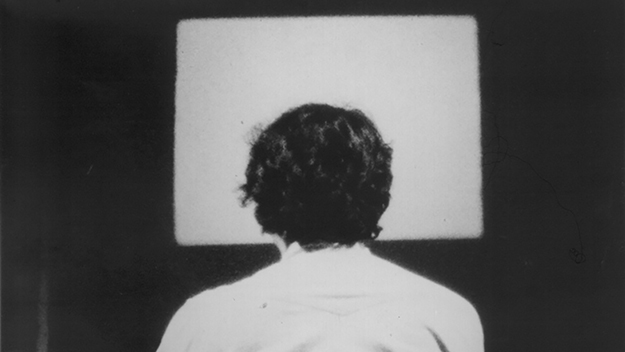

Talking Picture (Takahiko Iimura, 1981)

The lights are out. As I stare into the darkness, I hear a whir not only from the 16mm projector beside me but also from the ceiling, the screen, and the floor, as if the projector has expanded in size to fill the room. The film is running, but I see nothing. Then a mechanical click breaks the monotonous hum, and a moment later, a single white circle flashes in front of me. Over the next 20 or so minutes, there are more clicks and more white circles, until finally, I see only a white square. It is 2010, I am in the Bethnal Green Working Men’s Club in London, and I’ve just seen a rehearsal for the performance piece Circle and Square (1981) by Japanese experimental filmmaker Takahiko Iimura, in which he loops black film leader through a hook on the ceiling and then through a projector. As the performance proceeds, he punches holes in the filmstrip until eventually too many perforations break the loop. The film runs through the projector one last time before falling onto the floor, and a beam of uninterrupted light cuts through the space and onto the screen.

A few hours later, Iimura would perform the same piece for an audience at an event organized by Close-Up Film Centre, where I worked for several years. But this time, the performance lasted less than a minute. The holes that he punched were too close to each other, and the film ripped in a matter of seconds. Gently refusing our suggestion to splice the film back together and start again, Iimura chuckled, scratched his head, and reminded us that the white square declared the end of the performance. There was no going back.

While it confounded me as a 21-year-old, the commitment to chance that Takahiko Iimura demonstrated in this performance was typical of the artist; he approached every screening as an opportunity to breathe new life into his work. The fact that film is mechanically reproducible didn’t matter—for Iimura, who passed away on July 31 at the age of 85, celluloid was simply raw material that he used to access the singularity of a moment. Born in Tokyo in 1937, Iimura began his film career as an assistant director at Nippon Eiga Shinsha, a production company for promotional films, where fellow avant-gardist Toshio Matsumoto (Funeral Parade of Roses) also made a few early films. But the roots of his artistic practice lie in his high school years when he and his friends self-published experiments in concrete poetry that played with homonyms and the pictorial form of Japanese kanji characters.

Exploring different ways of approaching the same image or sound became central to his film practice. At a 1963 presentation of Dada ’62 (1962)—one of the seven works Iimura made in his first year of filmmaking—at Tokyo’s Naiqua Gallery, he treated the projector like a musical instrument, fluctuating the projection speed, pulling the projector lens in and out of focus, stopping and starting the film, and moving the image off the screen and onto the gallery wall. That same year, Iimura debuted his famous performance Screen Play at a show titled “Sweet 16” the Sogetsu Art Center, a multidisciplinary art space run by filmmaker Hiroshi Teshigahara (Woman in the Dunes). Iimura projected his 16mm abstract film Iro (Colors) (1962), which captures mutations of colored paint in water and oil, onto fellow artist Jiro Takamatsu’s naked back, his skin gleaming through a hole that Iimura had cut out in Takamatsu’s jacket in the shape of the projected image.

Even for the films he made for projection in the cinema, Iimura was constantly revising and generating fresh iterations, always resisting finality. He reedited his most narrative-driven film, Onan (1963), a surrealist tale of a young man exploring his sexual fantasies, every time it screened, adding scratches and holes and reordering sequences. In a 1965 essay for Eizo Geijutsu (Moving Image Art), he wrote that “there is no one version of Onan, but many works under the same title.” Circle and Square also has a double-projection version, and its premise echoes his other works, such as the film installations Dead Movie (1964) and Projection Piece (1968-72) and the performance Talking Picture (1981), all of which deal with the core elements of film exhibition—light and darkness, projector and screen. These elements were the true protagonists of his work. He preferred the Japanese term eiga (reflected picture) over the English term “motion picture” as he felt it better represented the state in which we watch films––seated, in concentration, with little motion.

Importantly, Iimura was instrumental in establishing the burgeoning Japanese underground cinema scene. Along with Nobuhiko Obayashi (House) and Yoichi Takabayashi, two of the few other Japanese filmmakers to use 8mm film, Iimura formed the Group of Three in 1964 to collaborate on public screenings of their small-gauge work. Later that same year, the three joined forces with filmmaker Kenji Kanesaka, critics Jyushin Sato and Koichiro Ishizaki, and American critic/curator/filmmaker Donald Richie to form the Film Independents, a group that was crucial to the development of a collaborative ethos and a sense of community in postwar Japanese avant-garde film. The collective organized “A Commercial for Myself,” an open-call showcase of two-minute one-reel films, for which they encouraged avant-garde artists and composers like Genpei Akasegawa and Yasunao Tone to take up the film camera for the first time.

Iimura also worked closely with many who became key figures of the Tokyo avant-garde: all three members of Japan’s leading underground art and performance group Hi-Red Center—Akasegawa, Takamatsu, and Natsuyuki Nakanishi—were his frequent collaborators; performance artist Sho Kazakura and Ankoku Butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata featured in his films; and composers Tone and Takehisa Kosugi, members of Japan’s first noise and sound art collective, Group Ongaku, composed several of his soundtracks. No less a figure than Yoko Ono dangled a microphone outside of her window in Tokyo to record street noises for Iimura’s film Ai (Love) (1962), in which two intimately intertwined bodies are shot in such extreme close-up that they become indecipherably abstract.

In fact, it was Jonas Mekas’s impassioned review of Ai in The Village Voice that encouraged Iimura to relocate to New York in 1966. The city eventually became his second home, which he shared with his wife, translator and filmmaker Akiko Iimura. There he encountered kindred spirits in underground cinema and the Fluxus experimental art community, and became a conduit between the Tokyo and New York avant-gardes as a writer and editor for Japanese publications like Kikan Firumu (Quarterly Film).

New technologies and techniques gave Iimura even more tools with which to explore the architectures of time and spectatorship. When he got his hands on video in 1969, he investigated the new medium with studious rigor. Recognizing the live-feed function as unique to the format, he staged the video performance Outside and Inside (1971), conducting interviews outdoors and showing them live in an auditorium. His installation TV for TV (1983)—which was featured in the 2018 exhibition “Before Projection: Video Sculpture 1974-1995” at MIT’s List Visual Arts Center—features two identical monitors facing one another. What’s playing on the screens is barely visible to the viewer; the piece forces us to focus instead on the apparatus and reflect on the mechanics of how a televisual image comes into being.

These experiments encouraged him to return to and contemplate the particularities of analog film, which led to a sustained engagement with structuralist filmmaking with works like 24 Frames per Second (1975-78) and One Frame Duration (1977). Unlike most flicker films, which attack our eyes, playing on the grey blur that emerges from the rapid oscillation between black and clear frames, Iimura’s structuralist experiments are patient and immersive: long periods of bright light are followed by sudden plunges into darkness, as though one is being swallowed whole by the the cinema space. On the occasion of Iimura’s first complete U.S. retrospective in 1990 at Anthology Film Archives, Mekas wrote that “he has explored this direction of cinema in greater depth than anyone else.” Even in his later years, he remained restlessly active, experimenting with the iPhone for interactive installations, producing and releasing DVDs of his own work, and writing reflections on his career—most recently for his 2016 book Eizo art no genten 1960 nendai (The Point of Origin for Moving Image Art: The 1960s).

Iimura’s works will be remembered as landmarks in Japanese experimental film and video, especially for the imaginative ways in which they redefined cinema through performance and installation. It is my hope that he will also be remembered as living proof that versatility—working between different media, between different countries, and together with different artists––doesn’t imply a lack of commitment. On the contrary, Iimura’s tireless curiosity allowed him ever-new angles from which to tackle the same set of questions about representations of time and the singularity of each cinematic moment. In a contemporary world saturated with proliferating screens, Iimura’s work reminds us to be attentive to the unique material and ephemeral dimensions of our encounters with images.

Julian Ross is an assistant professor at Leiden University Centre for the Arts in Society.