Rep Diary: Joaquim Pedro de Andrade

Brasilia, Contradictions of a New City

“If you want to understand Brazil, watch Brasilia by Joaquim Pedro de Andrade,” Adirley Queirós, one of the country’s most fervent political filmmakers, told me in August at the Locarno Film Festival. Indeed, both Queirós, whose film There Was Once Brasilia won special mention in the festival’s Signs of Life section, and the Brazilian directing team Juliana Rojas and Marco Dutra, whose socially driven horror movie Good Manners took home the Special Jury Prize, referenced Andrade as an ever-vital figure for today’s Brazilian political cinema.

Andrade was already an established filmmaker by the time he made the documentary short which Quierós praised—Brasilia, Contradictions of a New City (1967). Some of Andrade’s best-known works included Garrincha (1963), a nonfiction portrait of the famous Brazilian soccer player of the title, and The Priest and the Girl (1966), in which the arrival of a young priest in a traditional mining town brings on a clash of ideas and passions. The latter is a seminal work of Brazilian Cinema Novo, the movement that Andrade helped co-found, which was originally inspired on Italian neorealism and later had its own later offshoots such as tropicalismo (a more exuberant approach that is often ascribed to Andrade in later films, e.g., Macunaíma). As Cinema Novo was being recognized, Andrade’s work was central to its defining features: an emphasis on popular culture and the working class, as in Garrincha, where the soccer player becomes a new kind of national hero, risen from the midst of classe operária (factory workers); and keen criticism of Brazil’s atavistic social norms, as in The Priest and the Girl, in which a young woman, Mariana, is manipulated by a powerful diamond dealer who is also her adoptive father and with whom she has an incestuous relationship. In the latter, the dealer’s grip on the local community and on Mariana is finally broken when she runs away with a man of the Church who has come to her defense. This last plot point may seem unremarkable today, given how powerful the Church continues to be in Brazil, both the Catholic and the rising evangelical denomination. Yet the story’s unbridled passion, fueled by a woman’s open expression of Eros and captured by the movie’s fluid camerawork and elegant mise en scène, makes The Priest and the Girl one of the most memorable Cinema Novo films, right alongside Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s Barren Lives (1963) and Glauber Rocha’s Barravento (1962) and Black God, White Devil (1964).

Andrade’s cinema, showcased in New York at Anthology Film Archives in August, reveals Brazil of the 1960s as a powerhouse not only of popular culture but also of high art. Like Modernism before it, Cinema Novo’s success lies in mixing high and low, popular and academic modes, elevating folk narratives such as cordel (literally, “string” novels, cheaply printed booklets with folk stories and poetry) to the status of literature and thus reinvigorating the medium. Andrade’s films in particular are fueled by avant-garde modernist poetry (Carlos Drummond de Andrade, Mário de Andrade, Manuel Bandeira) and social sciences (Gilberto Freyre). Garrincha alludes to yet another modernist art form—photography. Interspersed with footage from soccer games are black-and-white stills from Garrincha’s private family scenes and of the crowds receiving the player enthusiastically in the streets that capture Rio’s unique urbanity. The images bring to mind the works of such photography pioneers as Gertrudes Altschul, Geraldo de Barros, and Thomaz Farkas, as well as foretell the rise of Latin American street photography.

Garrincha

Garrincha and The Priest and the Girl focus respectively on Rio de Janeiro (Brazil’s former capital) and Minas Gerais (one of the richest and historically most important states, known for its gold mines and baroque architecture). By contrast, Brasilia of 1960 is a blank slate—a megalopolis risen on the sprawling plateau, as a result of President Juscelino Kubitschek’s economic policies, Oscar Niemeyer’s brutalist architecture, and Lúcio Costa’s hopes for rational urbanization. Yet by 1968, Andrade already contextualized Kubitschek’s utopian dream of an orderly model city as a contradiction. Brasilia opens prosaically: in impassionate voiceover, poet and art critic Ferreira Gullar details the urban plans for Brasilia, its roots in the development of the car industry and, à la Robert Moses, in cities as satellites linked by highways. Unsurprisingly, Andrade enters the city by driving, the camera pointed to the road. The fluid tours alongside the residential districts, lined with trees and rectangular white blocks, between which children play unaccompanied, create a vision of Brazil that is orderly, clinical, safe, and strangely deserted. “The superblock is the reign of comfortable family life,” Gullar says, as we gaze through the window of a barbershop onto yet another patch of green amid concrete.

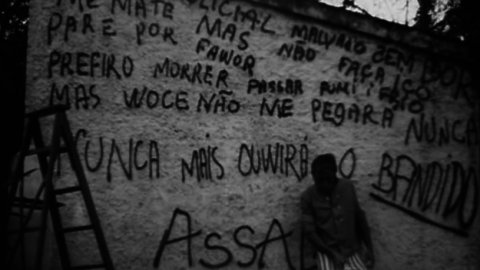

The film’s early discourse oscillates between two conservatives axes: the family and the Church. Yet Brasilia’s order is quickly perverted; its population acts in more organic ways. In one example, the main artery designed for trucks bustles instead with small shops and heavy pedestrian and car traffic. As a seat of power, abandoned by many intellectuals after the “crisis of 1965” (an allusion to both the coup that deposed progressive president João Goulart the preceding year, and to Andrade and Rocha’s arrest for organizing an anti-government protest), the city is riddled with overcrowded low-income housing and public schools where, as one teacher whose voice we hear in the voiceover puts it, “confused students wander the halls trying to find something to do.”

Andrade fully assumes the critical tone as we move from the comfort and effortless mobility of the car into workers’ homes in the center of town, and then, following the flux, to the outskirts (euphemistically called “satellites”). The handheld camera is accompanied on the soundtrack by Tropicalist movement’s muse, singer Maria Bethânia as she sings “Viramundo.” Similarly to the displaced workers in Geraldo Sarno’s Viramundo, the 1965 documentary for which the song was originally composed, Andrade’s viramundo (wanderer) finds his incarnation in Brasilia’s low-income labor. Forced from the area he has helped to build, he sees the urban world turn its back on him.

The Girl and the Priest

It is here that Andrade’s and Queirós’s visions intersect, with Brasilia as a dream forestalled, a ruin that nevertheless potentializes a revolt. In 1965 Bethânia, had already sung about the desperate fight against criminalization, a theme that Queirós emphasizes in There Was Once Brasilia with claustrophobic dark spaces, characters glimpsing the lights of the city center from afar, and with the prevalence of wires, grates, and bars. The world where men are shuffled silently on the metro, their imprisonment uncontested. Absolute powerlessness is the future—some would say, the ongoing present—in the dystopian Brasilia, where criminalization and crime have been normalized. With its worker interviews, Andrade’s documentary becomes a full-fledged denunciation. The film’s final trip is on the long, crowded bus ride that Brazil’s poorest workers take from the Northeast in hopes of making it in the capital. As the bus heads for the city, Brasilia’s concrete monoliths rising in the distance and the sky burdened with thick sleet clouds, the future looks crushing and grim. In this context, the ending, which sees the workers bustling on a construction site, feels more like a note of forced rather than genuine hopefulness.

Where The Girl and the Priest is an exercise in stylistic control, and Brasilia’s tone oscillates between informational and more outspoken, Andrade’s Macunaíma (1969) proves his cinematic exuberance, while being no less political. His highest achievement, the film weds all intellectual inclinations, from a revisionist stance toward Brazilian Modernism and a critique of Brazil’s economic “miracle” and military rule, to increasingly daring sexual politics. In the September/October 2007 issue of Film Comment, Olaf Möller rightly called Macunaíma a “deliciously funny, picaresque adaptation of Mario de Andrade’s 1928 novel, one of Anthropagy’s ur-texts.” Indeed, the 1969 film remains a delightful tour de force. This is partly thanks to its imaginative costumes, vibrant colors, and grotesque, allegorical form: Macunaíma, the title character (brilliantly played by Grande Otelo, a popular Afro-Brazilian chanchada actor who also appears in Werner Herzog’s Fitzcarraldo), is born an adult man in the Amazon jungle. He undergoes a physical transformation, from a “jet black” (as characterized in the opening of the novel) forest dweller to an urban white man, and the entire film—though to a lesser extent than the novel—is peppered with references to indigenous and African myths.

As Möller noted, Macunaíma’s passage from the forest to The Big City results in disappointment. To this end, when Macunaíma gets to the city—no longer a black man but instead metamorphosed into a young white prince (Paulo José, who also plays Macunaíma’s mother)—he remarks that he can no longer tell where “people end and machines begin.” But the film’s real bite lies elsewhere. For Macunaíma is that contradictory mix of features that most viewers would deem offensive: cunning yet lazy, he gets by with minimum effort. Greedy beyond belief, enterprising only when he takes advantage of others, Macunaíma is probably the closest in complexity in all of Brazilian literature to Shakespeare’s Falstaff, that unscrupulous, cowardly, fun-loving, libidinous prankster, whom Harold Bloom extols as one of the greatest antiheroes of all time. Macunaíma is also over-sexualized: a man of no physical appeal, he nevertheless stirs wild passion in all the women he meets. A wizard unaware of his powers, he is moreover ridiculously infantilized. In other words, he comes dangerously close to the noxious stereotype that the colonizers drew of a native “savage.”

Macunaíma

The film’s offenses don’t end here. In the film, women are witches, victims of or sexual predators themselves. In the City, Macunaíma meets a gun-toting urban guerrilla who at first rejects his advances, only to be knocked unconscious, molested (suggested by her being partially disrobed), and fall madly in love with him. What’s more striking though is Macunaíma’s surrender to her care, as a kept man. Guitar in hand, Macunaíma idles in a hammock, while his lover fulfills her revolutionary duties, maintains the house, raises their baby, and still saves enough energy for arduous sex that exhausts Macunaíma.

It’s unknown how long Macunaíma could have kept up this domestic bliss because his lover gets blown up (setting off a bomb to advance the revolutionary cause, we can guess). No doubt, it was daring of Andrade to poke fun not only at conservatism but also at the recently nascent leftist student militarism, including feminists. For if there’s one thing we can be sure of it’s that Macunaíma’s bodacious, savage humor is genuinely democratic, i.e., directed at everyone. A longtime collaborator, the acclaimed editor Eduardo Escorel (who also edited three of Rocha’s films, including Terra em Transe), attributes Andrade’s interest in making Macunaíma to the proclamation of the AI-5 (Institutional Act 5, a decree issued by the military regime, in retaliation for massive street protests) in 1968, and with it, increased censorship and the opposition crackdown.

Perhaps this is why the film and, by extension, its title character has been so popular with Brazilian audiences: Macunaíma is an outrageous embodiment of individualism and freedom, taken to the extreme. He is also too Rabelaisian in appetites and amoral to be taken altogether seriously. By debasing everything that’s sacred, Andrade seems to challenge Brazilians to take a more critical stance toward their past. As for Macunaíma, he ends up back in the jungle, alienated from his family, and eaten by a nymph, Uiara. Brazilian critic Ismail Xavier sees in Macunaíma’s fate a tragic dimension. In his 1997 book, Allegories of Underdevelopment: Aesthetics and Politics in Modern Brazilian Cinema, Xavier writes, “Macunaíma dies because he is unable to win the support of his own originary [sic] world . . . this world takes revenge for his attachment [to modernity].”

Macunaíma

Perhaps it’s in this indictment of modernity, and of the processes that lie behind Macunaíma’s failure to enlist the city as his ally and to reap permanent rewards from its riches, that Macunaíma links back to Brasilia, Contradictions of a New City. Indeed, if Macunaíma—as Andrade himself has said—stands for Brazil devouring its citizens, with poverty or underdevelopment, we can recall the contrast between Brasilia’s utopian egalitarian vision and its workers’ bitter struggles. This dark vision is also reflected in the film’s conclusion. Like the gangster in Robert Warshow’s essay, “The Gangster as Tragic Hero,” Macunaíma perishes so that a sense of moral order may be restored. The light-footed trickster, or malandro, as Brazilians call him, has ultimately served as a way of, in Xavier’s words, “exorcising the naïve faith in the virtues of individualism.” In the film’s final scene, the image of blood gives way to that of the Brazilian flag—a shift from Modernism’s affirmation of anthropophagy as the source of strength, by “digesting” traditions and cultures, to its darker, more Darwinian meaning.

“The Films of Joaquim Pedro de Andrade” screened August 23 to 30 at Anthology Film Archives.

Ela Bittencourt works as a critic and programmer in the U.S. and Brazil and is a member of the selection committee for It’s All True International Documentary Film Festival.