Remembering Amos Vogel: Be Sand, Not Oil

This article appeared in the November 11 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

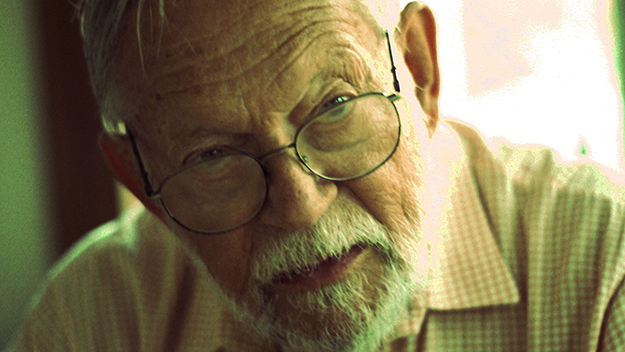

Amos Vogel, 2003. © Paul Cronin

It has been enormously gratifying to us, Amos’s sons, to hear about the many events—not only all around New York but also elsewhere (Vienna, Berlin, Zagreb, Pamplona)—honoring him in his centenary year. That even today, nearly half a century after the publication of his book Film as a Subversive Art (recently republished in a beautiful new edition by FilmDesk Books), and almost 75 years after the formation of Cinema 16, the film society he founded with our mother, Marcia, his views about film and film curation continue to be relevant to so many is a source of great pride to us.

We were especially pleased, and indeed moved, by the set of programs organized in his honor at the recent New York Film Festival at Film at Lincoln Center, and by the inauguration of an annual lecture series to be held at the Festival in his name. Amos’s relationship to the festival, which he co-founded and directed for the first six years of its existence, was a fraught one. He resigned in 1969 because he felt the festival was moving in a direction he could not support: he had high hopes for an expansion of a film constituency at Lincoln Center that would include a dedicated theater space and year-round programming, but instead he was faced by budget cuts and plans for corporate sponsorship that he felt would inevitably change the Festival’s nature for the worse. It became clear that he could not continue in his role. Given that sad experience, and indeed the anger that it caused (on both sides, we suspect), the fact that now after five decades the festival (today part of a constituency that includes several dedicated theaters boasting a robust year-round program) wanted to celebrate him felt like a welcome acknowledgement of his importance in the festival’s history, and even perhaps of the validity of some of the concerns he expressed at the time. We attended several of the events at Lincoln Center and were really pleased by the warmth with which we were welcomed, and by the respect and admiration with which Amos and his legacy were discussed.

Yet there was a central element of our father’s motivation and worldview that has struck us if not as missing then at least as having been to a certain extent minimized in many of the tributes to him, both at Lincoln Center and elsewhere: for his interest was first in politics, and only afterwards in art, and his interest in art was always centered on its ability to transform. Born in inter-war Vienna into a well-to-do assimilated Jewish family, from an early age he seems to have felt alienated from the bourgeois world he found himself in. As a teenager he joined the socialist Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair, a group skeptical of the high Western Kultur that hoped to develop in Palestine—in a bi-national state where Jews and Palestinians would be entirely equal—a socialist society based on a return to nature and the land. The Anschluss of 1938 and his family’s forced emigration to the U.S. delayed his plan to go to Palestine to help build kibbutzim, and then later the creation of a Jewish state in which the dream of bi-national equality was shattered decisively ended it: for the rest of his life, he was a resolute critic of Israel and supporter of Palestinian rights. In the United States he joined the Trotskyist movement, writing articles under a pseudonym for The Militant, and later served as one of the founding members of the editorial board of Dissent. For him Trotskyism seems to have represented a way to preserve the socialist values to which he was committed without supporting a Soviet Union that by the time of the Second World War had clearly become a corrupt, oppressive, and murderous dictatorship.

His direct involvement in Trotskyism waned in the late 1940s (as he and our mother began Cinema 16), although his scorn for “Stalinists”—of whom there were many in the left-wing Jewish New York milieu he inhabited, and who could not admit the truth about the USSR until Khrushchev allowed them to in 1955—never did. Later in life he called himself an anarchist. But whatever he was, what remained central to him throughout his life was a hatred of oppression and a commitment to the possibility of a better world, a world no longer marked by massive inequality in which those with money and power failed to recognize the dependence of their position on the exploitation of those below them on the social ladder.

The source of Amos’s interest in cinema lay primarily in film’s capacity to question the status quo—to help reveal the hidden truths of the bad world we inhabit, and at the same time bring about a better one, where people would no longer be subject to domination, whether by capitalism or religion or life-denying sexual taboos. His programming choices were always designed to shock and confront the viewers: to challenge them, change them, liberate them. And his notion of liberation did not end by any means at liberation from state or corporate or economic oppression but ran into the deepest parts of each person in the room (including himself): their sense of self, of decorum, of gender and sexuality, of reality. His book Film as a Subversive Art perfectly demonstrates all of this.

This anarchist in suit and tie never got over his youthful contempt for the bourgeois world. His insistence that film be taken seriously as an art form and that it should be presented on an equal footing with the other performing arts at Lincoln Center did not mean he was interested in or attracted to the world of “high culture” or to the thought of the rich of New York sitting comfortably in their furs and jewels with their season tickets, being lightly entertained by the latest celebrities and empty pap. We remember well his annual discomfort as he got ready for the black-tie Opening Night party, trying to figure out how to get into a tuxedo: he hated that kind of thing, and hated having to take part in it.

Beyond his passionate anger at the state (whether it be Nazis, Israel, the Stalinist USSR, or U.S. imperialism), at censorship of every kind, at mediocrity and the bourgeois status quo, he saw the rise of commercialism as a major threat to American life. The Hollywood system was as much of a perceived enemy to him as was Stalinist Russia and for similar reasons, because they could and did control and suppress what could be expressed. Amos saw the rise of corporatism and the power of money as a dire threat to humanity, and he spoke out about it early and often. Loring remembers watching the Academy Awards on TV with him when Charlie Chaplin was finally honored after years of being blacklisted, and the way Amos howled at the set in anger when the Esso logo was superimposed on Chaplin after his acceptance speech. It is crucial to note that Amos’s departure from the New York Film Festival was in part a protest against the idea that its financial struggles might be solved by taking on Philip Morris (!) as a sponsor, and against the inevitable commercialization such a move would produce. The festival we attended last month was wonderful in many ways, but it was hard for us not to look at each other and roll our eyes when before every film a slide appeared thanking more than 20 major corporate sponsors, or when we saw the table with festival “merch” (including an admittedly lovely Cinema 16 T-shirt). Amos liked to drink Campari, but we don’t think he would have been happy that the Campari company received special recognition as the “presenter” of the opening night—commercial, Hollywood—film.

Our father was committed to social justice, to the idea of a world where money did not rule, and to the constant questioning of cultural norms. The subversion he championed in his book was, above all, the subversion of a status quo that he hated until the end of his life. In his call for subversion he expressed an inexhaustible dream for the possibility of real freedom—from want, from oppression, from inequality, from repressive social convention. We hope that those who are celebrating him this year, and seeing him as a model, keep those ideals of his in mind. “Be sand, not oil in the machinery of the world.”

Steven Vogel is the Maria Theresa Barney Professor of Philosophy at Denison University in Granville, Ohio and is the author of Thinking Like a Mall: Environmental Philosophy After the End of Nature (MIT Press, 2015), among others.

Loring Vogel is an ocean swimmer, he has two sons, Jonah and Benjamin, Hitler failed.