Readings: Unchained Melody + Ghost in the Shell

Unchained Melody: The Films of Meiko Kaji

By Tom Mes

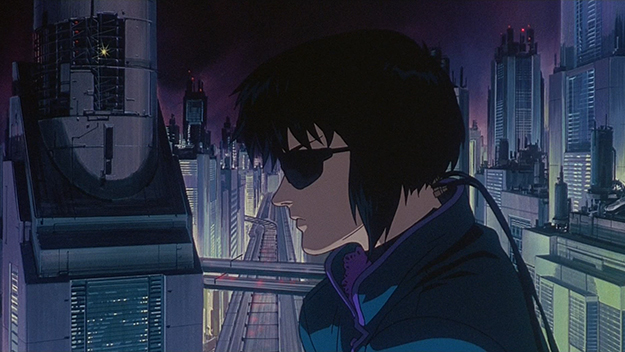

Ghost in the Shell

By Andrew Osmond

Arrow Books

Arrow Books is the new publishing imprint of Arrow Video, the UK-based, boutique home video label specializing in extras-rich box sets of restored horror, Japanese, and cult movie classics. They’ve begun with two cinema-related chapbooks squarely in their wheelhouse—Unchained Melody: The Films of Meiko Kaji, by Japanese cinema specialist Tom Mes, and Ghost in the Shell, by anime expert Andrew Osmond—followed by a third volume devoted to the Blair Witch franchise.

The idea of a video company dipping its toe into book publishing isn’t as strange as it might sound at first, particularly when you consider that Arrow Video (like The Criterion Collection, another specialty company with an eye on the traditional publishing industry) has already put together massive square-bound books of essays and other writing to accompany many of their limited-edition Blu-ray releases. In the case of this new venture, only one of the books bears any relation to titles within the Arrow Video catalog; the company doesn’t own the rights, for example, to any of the Ghost in the Shell films or programs. But Mes’s long-awaited book on Kaji connects directly to several titles within Arrow’s library, most notably its U.K.-only Blu-ray edition of her Lady Snowblood films (1973-4) and their box set featuring her most iconic performance, the four-film Female Prisoner Scorpion series (1972-3). Written largely without interview access to the actress (now 70), the book has been framed out of necessity as a sort of biographical filmography, detailing her career in film, television, and music through not only her major roles and works—some of them not widely available to foreign audiences—but also in relation to the filmmakers with whom Kaji worked most frequently.

Kaji has always been an iconoclastic figure within the Japanese entertainment industry, a factor which Mes underlines in the text. She refused to play by the rules established for actresses in the 1960s and 70s, and was never happy with her typecasting, first as a teenaged ingénue, then as a stoic and honorable warrior (during a brief period when Toei Studio promoted her a replacement for retired star Junko Fuji), and finally as a tough, vengeance-seeking outlaw. Kaji defiantly carved her own path through the industry, casting off her star status at the height of her fame in order to focus on smaller roles in productions directed by filmmakers whose work she respected. Kaji’s individualism and refusal to acquiesce to the typical demands of the studio system carried over into her personal life, as well: she’s become quite a reclusive figure, making public appearances only infrequently, and turning down most requests for interviews or other association with the genre films that made her famous.

Lady Snowblood

Mes relies on a critical consideration of her best-known films, and profiles of the directors (all men) who made them, in his assessment of Kaji not only as a performer but also as a unique and defiantly individualistic personality, particularly for the Japanese entertainment world, which thrived on conformity and predictability. Sadly, the scant Kaji interview material featured in the book, some of which comes from other sources, makes it clear that the actress has little love for the films which turned her into an iconic anti-heroine, also undoubtedly the films most admired by and familiar to anyone purchasing the book. Whether it was a distaste for the subject matter, often violent or sexual, or a discomfort working for Toei Studio (which was well-known at the time for sexual harassment and less-than-optimal working conditions for actresses), isn’t made clear. But one does get the feeling after reading the book that Kaji herself was not interested in the career seemingly cut out for her, because of her clear disdain for the types of films and roles which made her not only famous but also distinguished her from hundreds of other actresses working in the Japanese industry at the time. In the interviews quoted in the book, she devotes most of her love to bland television performances or her three collaborations with director Yasuzo Masumura (only one of them a starring role, and one which resulted in great antipathy between the star and filmmaker). The elements of her characters which have made viewers in Japan and abroad fall in love with her Snowblood and Scorpion films go strangely overlooked by the star: her toughness and uniqueness among Japanese actresses both then and now.

Thankfully, Mes is able to fill in the gaps between her best-known films as well, with well-researched chapters on her television work and music career, as well as her less-well-known collaborations with Kinji Fukasaku and Masumura. A couple of copy errors creep into the text (Scorpion screenwriter Fumio Konami is mistranslated as Kannami, and the actress who portrays Yuki’s mother in the first Snowblood is misidentified—it should be Miyoko Akaza, director Fujita’s wife), but otherwise the book is an enthralling read, well-illustrated and designed, which leaves the reader happily wanting more. Luckily for us, there are still plenty of films available to give us the fantasy of Meiko Kaji, if not the harder-to-pin-down reality.

Ghost in the Shell

In contrast to the Kaji book, Osmond’s Ghost in the Shell gives the reader almost too much information. An exhaustive catalog of the production history of the landmark original 1995 animation by Mamoru Oshii, the book also looks at Masamune Shirow’s source manga and the various spin-offs and sequels made over the years, undertakes a critical consideration of the film’s deep themes, and considers its connection to Blade Runner, the Matrix series, and other related sci-fi works, ending with a brief evaluation of the 2017 live-action American remake with Scarlett Johansson. While very informative and exactly the kind of deep, single-film analysis which something like Ghost in the Shell deserves, the book is a bit of an awkward read, not really making any attempt to cater to an audience that’s not already extremely familiar with the Ghost in the Shell franchise and Japanese anime in general. (Mes’s book, on the other hand, approaches Kaji as a subject new to the reader.)

That said, Osmond does go out of his way to dispel many of the myths surrounding the film and its spin-offs, as well as recognize the significance of the original film and its watershed arrival on the SF and anime scene. Additionally, his background information on the artists who made the anime classic—including long-overdue biographies of the voice actors and animators that hasn’t appeared in English before, to my knowledge—is historically valuable and, particularly for a book that’s ostensibly about a single movie, wide-ranging in the best possible way.

Marc Walkow is a writer and film programmer living in New York. Formerly a director of the New York Asian Film Festival, he has also produced DVDs and Blu-rays for Criterion and Arrow Video.