Queer & Now & Then: 1971

In this biweekly column, I look back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

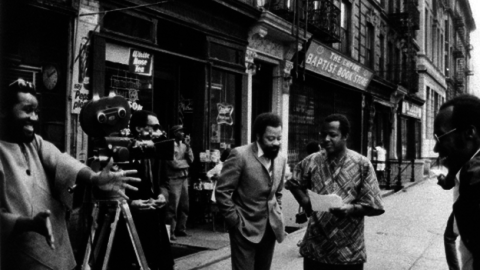

Just the title itself is pretty damn queer. Probably the most entertaining daunting-sounding American movie of all time, William Greaves’s Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One, shot in 1968, finished in 1971, shelved by its director until a Sundance premiere in 1993, and not given a proper theatrical release until 2001, never quite fit into any of its times. In broad outline a “behind-the-scenes” documentary about the shooting of a movie that was never really intended to be a movie in the first place, Greaves’s daring—and daringly nonchalant—whatsit turns a bemused eye on the moviemaking process, investigating the various hierarchies and social power games that exist on a film set and by extension the world at large.

From the title on down, it’s clear that Greaves, who appears as a version of himself on screen, has as little interest in putting the viewer at ease as he does his emotionally ragged actors and frustrated crew. Feeling like they can’t get a handle on Greaves’s befuddling methods, apparent lack of discipline, or the bizarre, free-form psychodrama script he forces his actors to angrily shriek through, the crew is at sea, leading to a minor mutiny. The camera and sound people squirrel themselves away and record their own annoyances on film, unbeknownst to the director (or is it?), who ultimately edits them into the final movie as a sort of subplot. The crew’s general “what the hell are we making?” irritation easily segues to the audience’s “what the hell are we watching?” feeling, though it’s undoubtedly more pleasurable for the latter, contained as the film is within 75 fleet, expertly jarring minutes of screen time. Complicating matters in no minor way—and making the film even more singular—is the fact that Greaves is an African-American filmmaker presiding over a crew of predominantly white people, which loads their insistent distrust of his artistry and methods with sociopolitical weight, i.e. implicit racial bias. It’s all tricky territory, but, as overseen by a brilliant trickster, it’s a work of almost invisible calculation, an emotionally fueled intellectual experiment.

It’s a testament to the film’s multitudinous, inchoate nature that even the above, admittedly convoluted description barely begins to do justice to the many provocations that effortlessly ping and pong around Symbiopsychotaxiplasm. Any given piece of criticism about it could choose to focus on one of the variety of dynamics or ideas that plays out, and I should know: this is the fourth time I’ve written about it over the past decade-plus in various places. So why go back to this endlessly replenishing well yet again? Because of all the inroads I’ve made into the film—my previous articles have been about, in order, the centrality of its 16mm camera and sound equipment, the rich diversity of its Central Park shooting location, and the sly racial politics that emerge via the performance of its director-star—I have yet to talk about Symbiopsychotaxiplasm’s odd, complicated, and endlessly amusing discussions around sexuality and specifically homosexuality.

It’s not like this is hidden below the surface—in fact, it’s a preoccupation of the film. Near the beginning, Greaves himself casually says to some crew members in earshot, “Everything that happens on the set, whether it’s off camera or among the crew or whether it’s being shot, thematically, we should be constantly relating to sexuality.” Why this might be is as vague as the parameters and intentions of the relationship breakup film he’s purporting to make. It’s called “Over the Cliff,” he tells a group of curious African-American and Latinx teen bystanders; the title is a clear bit of jokey self-reflexivity—this film is clearly sending them all over a cliff. It consists of a series of wildly irritating, ever more histrionic fights between a husband and wife as they wind their way around the park in broad daylight. Various men and women play the roles of “Alice” and “Freddie,” some are black, some white, some sing their dialogue as though captives in some acting exercise gone wrong. The vengefully emasculating Alice is fed up with Freddie, slinging improbable, sub-Albee daggers like, “You’ve been killing my babies one right after the other!” and “Since we’ve been married I’ve had abortion after abortion!” But the crux of Alice’s rage seems to come from the fact that Freddie’s not the man he would appear to be: “I’m a woman, and not a fool, Freddie. I watched you and I watched him. Him, yes, him. Some little faggot boy that half the world knows about.” The homophobic slurs and bizarre references continue to fly, until Alice is tossing her head around, sing-screaming “You just want the gay world. G-A-Y!” and hurling presumably improvised insults at Freddie about fucking rabbits or mosquitoes. In these moments, the film almost explicitly—and provocatively—verges on camp (the audience always laughs here, in all the times I’ve seen the film). All the while, Freddie has a slow public meltdown of denial: “You’re projecting, Alice. You’re trying to see things in me that you see in yourself!”

While the cast is purposely interchangeable throughout the film, making Alice and Freddie seem more like parts than people, we mostly are cursed to be in the company of main actors Patricia Ree Gilbert and Don Fellows (who looks like a cheapjack Bob Newhart). Gilbert and Fellows somehow make their characters even more objectionable than one could imagine on the page, tapping into subsumed rages that feel as though they’re targeting Greaves as much as each other. But it’s off-camera (which, in this film, is always on camera) that they come across as most haplessly neurotic—and, in Fellows’s case, cluelessly offensive, even considering the parlance of the times. Fellows at one point pulls Greaves aside on one of Central Park’s footbridges to talk about his approach to the character: “I don’t know whether to play a bisexual . . . I don’t know whether this is a faggy fag or a butch fag.” After an amusing, brief, and seemingly unmotivated camera pan over to a shirtless stud passing under the bridge in a rowboat, he concludes, “I’d like to play him as a closet fag . . . So I’ll just go ahead and play it straight.” In other words, play it safe. Greaves laughs—presumably at the actor’s desperate contortions to come out on top, brave yet masculine—and walks away, shaking his head and muttering, “It’s too much.”

What are we to make of all this? There’s no doubt that the content of the discussion—putting aside its tenor for a moment—would have been highly unusual in American cinema of the time, but even the few experimental or avant-garde films of the period that conversed in any way with issues around homosexuality did not often have such direct dialogues, and certainly not those that would expose such casual homophobia. The first takeaway is the surprise that this lexicon of “faggotry” would be mainstream enough to be spouted by ostensibly straight men, even if they may have been exposed to gay men through the arts. As Amy Taubin writes in her Criterion essay on the film, “One of the most interesting aspects of the film’s focus on sexuality is that, at this point in 1968, the political discourses around feminism and homosexuality were only beginning to be articulated.” But by the time of the film’s final assemblage and first screenings in 1971, Stonewall would have already happened, and likely mainstream viewers might find Fellows’s rant less exotic.

The discussion itself—and Greaves’s insertion of an allegedly closeted gay character into his precarious narrative—is intriguing for reasons beyond its being captured for dubious historical posterity, however. The intentionally banal dialogue of this tepid psychodrama engenders a conversation amongst the crew that says a lot more about sexual and societal roles—and the sexist blind spots around those roles—than any written drama of the day would dare. After complaining about “being forced to listen to this sordid conversation” over and over, soundman Jonathan Gordon insists, in his preening late-’60s liberal way, that a “faggot is not a homosexual—faggot is a kind of mentality,” observing that Greaves is making a statement about emasculation rather than sexuality. He yearns for the kind of authenticity that such an evidently trite script could not reveal, that movies would be more honest if they vividly and directly described sex acts (“Talk real language . . . Freddie has a cock, Alice has a cunt, Freddie likes or doesn’t like to fuck Alice”) rather than proffered vague sentiments about love and relationships. (It’s worth noting that Cassavetes’s Faces, perhaps the kind of stripped-down confrontational cinema that Gordon wants, was just months away from making its New York Film Festival premiere.) Gordon here presumes therefore that Greaves’s references to homosexuality are mere dalliances, distractions from the real meat of the problem, which is, as ever, the union between a man and a woman.

What Gordon also wasn’t taking into proper account—or perhaps understood too perfectly—was that Greaves would have been well aware of the excoriating normalcy of this couple and the terrible banality of his dialogue. Greaves was a longtime Actors Studio member and, just one year after he shot Symbio, became a teacher at the Lee Strasberg Theatre Institute for more than a decade. A veteran of the stage and documentary film (his landmark Still a Brother: Inside the Negro Middle Class aired on PBS in 1968, and he was at the time an executive producer of the series Black Journal), Greaves was not just cognizant of the social/political/racial/sexual limitations of Method acting in general, he was spotlighting them and pushing them to their breaking point. Writes Shonni Enelow in her description of the film in her book Method Acting and Its Discontents: “Method acting acknowledges the crisis of scriptedness: the crisis of the script’s suddenly apparent, apparently incontrovertible, inadequacy.” Greaves’s putting his actors through these agonizing motions—and agonizing, heterosexual panic—was not just game-playing for its own sake. Such acting exercises expose Alice and Bill as social constructs. As a result, their witless, homophobic dialogue comes across as nothing less than the last gasps of a whiny, feckless bourgeoisie.

If Alice and Bill (and Gilbert and Fellows) can’t get to the core truth, to that realm of authenticity that everyone seems to desire, whether it’s actor, director, or camera- and sound people, then perhaps the film has to cede its inquiries to a different kind of reality. That reality comes calling in the unexpected final passage of the film, when a proudly drunk and rather dandyish homeless park-dweller named Victor interrupts the shoot, looking for cigarettes and someone to gab with—or, more aptly, at. Victor, who says he’s a painter who attended Columbia and Parsons School of Design, functions here as a free agent in many ways—he’s someone who lives outside of the rules of contemporary society, and also an unexpected filmic element who helps underline the contingency of documentary practice itself (his presence and ultimate centrality to the film also reminds one that the Heisenberg Uncertainty Principle and its attendant “observer effect” was one of Greaves’s motivating forces in making the movie). Victor throws the entire film into relief: he is effortlessly charming where Alice and Bill are caustic and nasty; he is direct and bullshit-free where Greaves is sly and evasive; he is secure and proud where Gilbert and Fellows are neurotic and anxious about themselves and the image they project. Using blithe, almost fey gestures and waves of the hand, he gets at bitter truths everyone else is desperate to find. At the same time he’s as much a performer as anyone else on screen, perhaps naturally even more so. He indifferently implies that he’s performed fellatio (“Everybody sucks!”), shrugs off binary gender constructs (“You’re a lady, I’m a lady too, I’m a man”), and calls everyone “dahling” in such an open way the viewer momentarily forgets the agitation all the other on-screen principles have been causing and experiencing for so long. Seeing him wander away through the park, off into the great unknown at film’s end, one might feel relief and sadness and envy all at once. Victor, untethered to all social decorum, is one of American documentary cinema’s great stealth queer characters. Perhaps Greaves’s greatest trick was making him his star.

Michael Koresky is the Director of Editorial and Creative Strategy at Film Society of Lincoln Center; the co-founder and co-editor of Reverse Shot; a frequent contributor to the Criterion Collection; and the author of the book Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press.