Queer & Now & Then: 1969

In this biweekly column, Michael Koresky looks back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

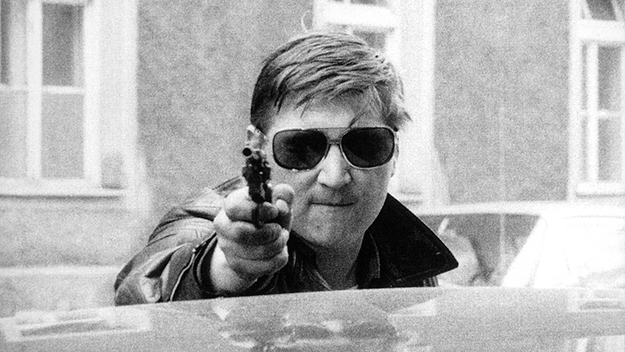

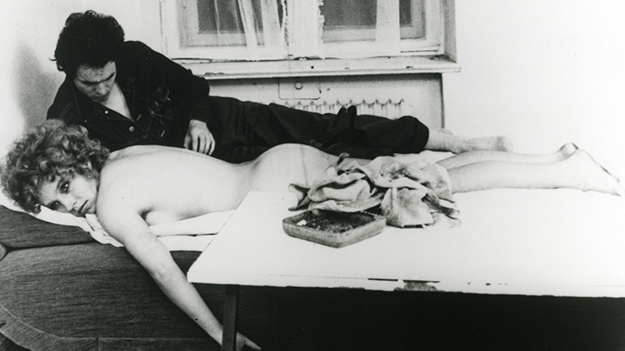

Images from Love Is Colder Than Death (Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1969)

There have been so few true rebels in film history—one of the many reasons we can’t stop talking about Rainer Werner Fassbinder. From the very beginning of his career, it’s clear he was not eager to ingratiate himself with the film world. His debut feature, Love Is Colder Than Death, premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival in 1969, and was immediately met with divisive reactions from a vocal audience. The myth goes that it was roundly booed in the theater, but footage shows that as the curtain went up and lights came in, there were a smattering of “Bravo”s alongside the shouts of “Dilettantism!” and “Pure nonsense!” Against the tepid viewers in the auditorium, who had been put off by the film’s detached aesthetic and undiluted nihilism, Fassbinder feigned triumph rather than acknowledging defeat. At the subsequent press conference, when one journalist stated, “From what I hear, you wish to destroy society,” the filmmaker remained calm, even bemused. It’s clear, even today, that he was no callow narcissistic provocateur but an artist on a mission to challenge and confront, if necessary, and, more importantly, create.

Fassbinder was, of course, undeterred, going on to direct ten movies in just the next year and a half alone, and more than forty features total before his death in 1982 at age thirty-seven—an output unmatched in furious ambition and skill. Love Is Colder Than Death’s visual schematics and genre experiments undoubtedly intimate evince a director in the early stages, trying out a new look, in this case one more influenced by concurrent late-’60s French filmmakers like Godard and Jean-Marie Straub than his later efforts would show. Yet so many of the various elements that came to define Fassbinder’s career are already here, remarkably, in this apathetic yet meaty riff on the gangster melodrama (shot in only twenty-four days): the subversion of American genre codes; a focus on those at German society’s economic margins; the increasing materialist complacency of his countrymen; the “tie between love and violence,” as he put it in the post-screening press conference in Berlin; and, perhaps most remarkably, a genuinely fluid depiction of identity, sex, and love that reflected the director’s own matter-of-fact bisexuality.

Fassbinder is looked back on so fondly by generations of cinephiles that it’s easy to forget how unloved he once was. Cinema in West Germany was embattled throughout the sixties, with a new generation of the country’s filmmakers demanding a rejuvenation of the art form following decades of safe, nationalistic movies that refused to reflect its post–World War II realities. The Oberhausen Manifesto, written by a group of up-and-coming directors including Alexander Kluge and presented at the 1962 edition of the International Short Film Festival Oberhausen, was a call to action, both for filmmakers and government financiers in charge of cultural institutions and commissions. Years later, when government-financed films started to come to fruition, the public couldn’t have been less interested in the results, finding them overly esoteric and noncommercial.

Fassbinder was slightly younger than these original arbiters of the New German Cinema; he had nothing to do with the Manifesto, yet agreed that his country’s cinema was stale. In the late ’60s, he was more involved in experimental theater; in terms of movies, he preferred Hollywood imports, especially melodramas and gangster films, as well as films of the trendier European New Waves. While his first two short films—financed by an out-of-work actor boyfriend—were rejected by the Oberhausen Festival, he moved right ahead with making his first feature, this time with his own money raised from acting jobs. He convinced Uli Lommel, his costar from Volker Schlöndorff’s Brecht adaptation Baal, and Hanna Schygulla, whom he had met in acting school and was part of Fassbinder’s “Antitheater” collective, to take the lead roles opposite him. The result was the first steps towards a new New German Cinema, a kind of restart button that would also launch one of the most astonishing, go-for-broke careers in film history.

Fassbinder’s cinema announces itself in a bleak and beautiful first image, a stark, black-and-white composition in which the leather-jacketed writer-director-star himself reclines cross-legged on a chair, cigarette dangling from his lips, reading a newspaper; he’s pushed to the left of the frame, leaving an expanse of white cement wall to take up most of the screen’s negative space. Both because of the stretch of time during which the scene plays out and because of the sterility of the environment, it seems as though Fassbinder’s character, Franz, is in some sort of waiting room. In the same take, a man in a suit—played by Antitheater member Kurt Raab, who would continue to be a player in Fassbinder’s loyal, beleaguered film troupe—walks up, snatches the paper from his hands and asks for a light; instead Fassbinder coolly gets up and slaps him across the face, sending him to the floor with a bloody nose. A bare-chested henchman in sunglasses, Raoul (Howard Gaines), wearing only a gun-holster over his torso, enters from a side door, summoning our antihero from this Beckettian nowhere.

All of this is expressed with a kind of detached indifference, as though everyone on-screen has given up before the movie’s even begun. Arch blocking, notable pauses between lines of dialogue, and stylishly unstylish sets drained of detail speak to Fassbinder’s early art-film influences. Later in his career—only a few years but nearly a dozen films away—Fassbinder would play with the colorful conventions of Sirkian melodrama; here the aesthetic keeps you at an emotional remove. Soon, another starkly lit room, where Franz sits immobile, blindfolded, smoking. While interrogating Franz, a man—clearly a crime boss of some sort—sits next to Raoul, suggestively rubbing the other man’s knee. The forbidding barrenness of this grim underworld permeates everything, yet so does a free-floating homoeroticism. We come to learn that Franz is a small-time hood who’s being pressured to join the ranks of a crime syndicate. “Do the work and you’ll be paid regularly,” promises his potential employer. “I work for myself and no one else,” says Franz, an ethos that would also inform Fassbinder’s career.

Though Fassbinder himself, with his attractive pinched loner snarl and pornographically tight pants, is a compelling screen presence, it’s Uli Lommel’s Bruno whom Fassbinder’s camera adores. The young actor plays Bruno, a criminal whom the syndicate persuades to help them in surreptitiously getting Franz on their side by implicating him in a crime. When we first see Bruno, it’s a full 60-second medium shot of the boyishly handsome Lommel, sporting a suit and tie and tousled hair; the actor stares directly to camera, a near Mona Lisa smile on his face, as though he wants to share a secret with the viewer. Franz will find Bruno as appealing as Fassbinder does: an intimacy grows between the two men during their days in captivity, leading Franz to invite to his apartment in Munich, where he lives with his prostitute girlfriend, Johanna. As Franz gives Bruno his address—in a suggestive composition that finds Fassbinder turned, his back to the camera, those painted-on trousers ever beckoning, so close to Lommel their bodies are nearly touching—violin music swells, the hint of an impossible romance.

As if to leave no doubt about Lommel’s status as erotic object, for most of the remainder of the film he is dressed in fedora and trenchcoat in direct reference Alain Delon in Le samourai. When he arrives at Franz’s apartment in a depressed, vacant Munich, Bruno is greeted with a quick frisk by Franz, who comes up from behind and places his hands on his friend’s chest; in this moment, the camera emphasizes their contact by doing something unusual in this otherwise static film: subtly zooming in on Bruno while Franz is tenderly patting him down. It’s noteworthy that Franz appears decidedly more interested here than in the moment right before Bruno’s arrival, in which Johanna—played by the marvelously nonchalant Schygulla—takes off her pantyhose while he looks the other way, fidgeting with his gun. Packing heat, Franz is paranoid after being falsely fingered for killing a local Turk and is hiding out from the murdered man’s brother who’s out for revenge. “He can’t shoot you if you get him first,” advises Bruno, whom Franz doesn’t seem to think could have ulterior motives. Franz can’t stop looking at Bruno; Bruno, however, seems to be wholly preoccupied with Johanna.

The wayward criminal endeavors in which this tenuous ménage à trois proceeds to engage in, including a misbegotten attempted robbery and a final violent betrayal, are far less enthralling—perhaps intentionally so—than the low-key love triangle that develops between them. In one scene, Johanna lies on their apartment floor, her eyes closed, while the radio plays; while Bruno crouches beside her, unbuttons her shirt and starts to kiss her on the cheek, Franz watches from his bed in the back of the room, seemingly only too happy to share her with Bruno. Franz’s voyeuristic pleasure—if that’s what passes for pleasure in this highly subdued, recessive world—is only shattered when Johanna giggles at Bruno’s attempt at eroticism. Afterwards, Franz slaps her across the face. But it’s not because he’s been humiliated by the potential cuckolding. “What was that for?” “Because you laughed at Bruno, and Bruno’s my friend.”

Fassbinder’s threesome functions as both a commentary on the homoeroticism of the classic gangster film, while also pointing towards a filmography in which the sexuality of his characters would be as fluctuating and capricious as their economic fortunes. As his debut feature’s title implies, the world that Bruno, Franz, and Joanna inhabit is a chilly one, in which our antihero crooks are not cool, principled career criminals but easily exploited, backstabbing saps struggling for survival. They even carry a dummy submachine gun, as it’s all they can afford. There’s nothing romantic about their livelihoods, and there’s no liveliness to their romance, either. Ultimately, Franz’s queer love for Bruno goes unrequited, but neither will Bruno and Joanna end up together. Only Fassbinder would kickstart a career with such a neutered trio. It’s understandable their failed escapades would turn viewers off. Thankfully, those boos at Berlin would only fan the flames of his perverse pleasures.

Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer and Now and Then; and the author of Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press, 2014.