Queer & Now & Then: 1951

In this biweekly column, Michael Koresky looks back through a century of cinema for traces of queerness, whether in plain sight or under the surface. Read the introductory essay.

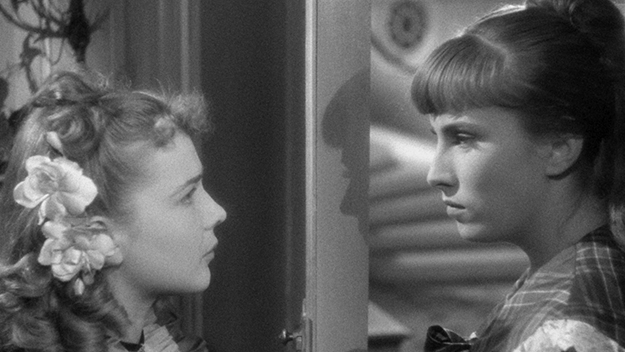

Images from Olivia (Jacqueline Audry, 1951)

“Now I must bid farewell to all that I love.” It’s a line that comes late in Olivia, and though it’s one of the many grandiloquent, intensely delivered emotions that buffet this strange and beautiful film along its winding way, this moment hits particularly strongly. It’s spoken by a disintegrating Miss Julie (Edwige Feuillère), headmistress of a girls’ boarding school, to a pupil, Olivia (Marie-Claire Olivia). At this point, Olivia’s eerie adoration of the older woman has reached epic, all-consuming proportions. The older and younger woman are not in a classroom, but in Olivia’s bed, where the two are locked in a sensual embrace that goes far beyond pedagogically appropriate behavior.

There is ambiguity here: what or who is it that she is bidding farewell to? Is “all that I love” the school itself, with its cadre of young, starry-eyed girls learning about Victor Hugo and Aeschylus, Chimène and El Cid? Or is it the frail Miss Cara, the vaporous woman across the hall who always seems to be recuperating from a mysterious illness? Or is it Olivia herself that Miss Julie truly loves? The romantic-tragic classicism of Miss Julie’s line of dialogue—she has announced her decision to leave the school following a scandalous incident—perfectly matches the visual composition of the supine Olivia cradled by her beloved mentor; at one point their lips are nearly touching, like an angel bestowing a kiss on a cherub.

It’s a highly unusual scene for a film made in 1951, but Olivia would have been highly unusual at any point in cinematic history. It’s now widely accepted that emotional complexities did indeed roil beneath the visually staid surfaces of so many of the French “cinema of quality” films of the forties and fifties derided by the Cahiers du cinéma critics who would become the transformative Nouvelle Vague auteurs; Olivia is a particularly extreme example of just how much irreconcilable sexual longing and psychological intensity can be crammed into the corners and crevices of an otherwise seemingly cosseted mise en scène.

Olivia is the newly restored revelation by filmmaker Jacqueline Audry, one of the very few female directors working in French cinema at the time, and she seems to be even less known today than she was then, which is to say not at all. In the thirties, Audry had started out as a script girl and as a directorial assistant to filmmakers such as Max Ophüls and Jean Dellanoy, and had begun directing her own films in the forties, including multiple Colette adaptations. Olivia, her fifth feature, is a work of bold, barely repressed sensuality, in which the simmering, unspoken, but ever-present love between women threatens to boil over into drama of Dido and Aeneas proportions.

Olivia fits snugly into the cinematic tradition of using a boarding school setting, with its potential for unsentimental education, as a breeding ground for tentative lesbian attraction—think of everything from Mädchen in Uniform to Diabolique to The Children’s Hour to The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie—but Audry’s film goes way beyond innuendo, while still stopping just shy of the full-on romance it desperately wants to be. The film is based on anonymously published, and autobiographically tinged 1950 English novel of the same name written by Dorothy Bussy, whose queer bona fides are rather remarkable: the bisexual Bussy’s younger brother was Lytton Strachey, renowned gay writer and critic; she was involved in an affair with renowned arts patron Lady Ottoline Morrell; and was friends with André Gide and E. M. Forster. The film version of Olivia allegedly tones down the more outward gay content of her book, but the overall atmosphere it maintains is quite extraordinary; it all but luxuriates in an always imminent queer lust.

Taking place at some point in the nineteenth century, Olivia begins in perfect novelistic form, as the title character is arriving to her new abode via carriage. She’s getting a little anticipatory lay of the land from the wise housekeeper and cook Victoire (Yvonne de Bray, the film’s Marjorie Main-esque secret weapon), who makes casual yet ominous reference to a “tragedy” but otherwise remains cheerful about Olivia’s arrival at the school. For her part, Olivia is wide-eyed, yet there’s something unsettlingly knowing in her visage; she has the face of someone who’s plotting something, but it also might just be wicked self-determination. Olivia comes with her own past connection to the school—her mother was a friend of the headmistress many years earlier.

When we first meet Miss Julie, her entrance is appropriately dramatic, emerging from the top of the foyer’s staircase landing, ensconced in lace. The grand dame is less imperious, however, than beseeching, a woman who appears to have as much love to impart as lessons to teach, and Feuillère, a veteran of screen and stage, who began in the Comédie-Française, plays her with an exquisite negotiation of delicacy and diamond-hard no-nonsense. If Miss Julie seems like a woman torn, there’s a very present reason for this: the school is home to another elegant yet brittle, more emotionally volatile mistress: Miss Cara, played by Cat People’s eternally feline Simone Simon. As the film progresses, we come to realize that Miss Julie and Miss Cara are engaged in something of a cold war, the origins of which remain ambiguous, but which captures the imagination, hearts, and souls of the student body. Victoire at one point says that the school is divided between the “Julists” and the “Carists.” Little does Olivia know that some of the girls have even already taken bets about which camp she will fall in.

On her first night, Olivia is already summoned to Miss Cara’s quarters; it’s “a great honor she does you,” insists Frau Riesener, Cara’s forbidding, Mrs. Danvers–like, German maid, whose hair is pulled tightly into a wreath that might as well be a coiled snake. Olivia asks her new confidante Mimi (Marina de Berg) if they will be reading passages from the Bible with this mysterious second mistress, a post-meal custom from her previous school, a place defined by a religious dread, where they were constantly warned about the trap of temptation. Mimi laughs off the thought; Miss Cara’s pleasures must be less traditionally devout. Upon entering her room, Olivia and Mimi find Miss Cara lounging exquisitely; trying to rest off her migraines and vapors, she asks the eager girls to do her bidding, replace her shawl, fluff her pillows, make her a hot cologne pad. Rather than a gothic Brontë-esque woman in the attic, Miss Cara is bitter and love-ravaged, and overly tended to by Frau Riesener, who won’t let her outside to walk around the school’s bucolic grounds, even after dinner, due to her mystery illness.

Yet Miss Cara is hardly the only character who seems to be under a spell. As inhabited by Marie-Claire Olivia—an actress who only appeared in two other movies and who reportedly legally changed her name to match her title character here, a strange piece of trivia that’s entirely in keeping with this film’s odd, free-floating sense of possession—the girl seems led by some unspoken internal desire. After an evening reading in which Miss Julie relates the story of Hermione, the other girls notice her ethereality, “walking as if in a dream.” Miss Cara appears to have tried to seduce Olivia away, but Olivia is enraptured by Miss Julie. What seems to start out as a schoolgirl crush becomes ever more intense. On a trip to Paris, the headmistress shows her Watteau’s “The Embarkation of Cytheria,” but Olivia can barely pull her eyes away from Miss Julie to even glance at the rococo landscape; on the train ride back, Miss Julie grows so unnerved by Olivia’s intense stares from across the compartment that she asks her to move next to her instead. Of course, Olivia then clutches at her hand instead.

The sort-of triangle that emerges amongst Olivia, Miss Julie, and Miss Cara comes to feel like an internal battle of wills with no possible victor. Cara loses the devotion of Olivia, who is desperate for the attention of Julie, who in turn is nursing long-untended wounds related to Cara; all of these loves seem both impossible and hugely consequential, a bursting-at-the-seams queer desire elevated to romantic agony. Audry sets this combustible craving within a labyrinthine interior space of vertiginous high angles; the school’s imposing staircases, window lattices, and marble patterned floors evoke a pressing claustrophobia. The film’s overwhelming expressivity reaches its apex during the school’s annual Christmas ball, in which the women dress up for one another in a kind of holiday pageant cum fashion show, which seems to allow them to let go of their inhibitions. At one point, Miss Julie grabs student Cecile, dressed up as “America,” and all but ravishes her, kissing her on the neck. Emboldened, she sidles up to Olivia, who’s wearing a teasing, gauzy sheik-like veil. Well aware of Olivia’s crippling crush, she nevertheless further plays with her, telling her she’ll come to her room tonight, and bring her “candy.” Later that night, we see Olivia lying in bed, waiting for Miss Julie’s arrival, in tears. She never comes.

Audry’s film is propelled by these kinds of casual cruelties and sexually ambiguous motivations. In this all-female world—men only appear very briefly as abstracted authority figures, often shot from behind—the characters’ erotic passions are somehow both proudly out in the open and necessarily sublimated. The film’s ghastly alternate U.S. title, The Pit of Loneliness, speaks to what a film about repressed female queer desire might have been in someone else’s hands. One can imagine a less sympathetic, male director, for instance, filming this as a story of miserable, doomed women. Instead, Olivia all but bursts with promise for the eventual fulfillment of lust, of the hope for emotional and spiritual and sensual and artistic connection.

Michael Koresky is a writer, editor, and filmmaker in Brooklyn. He is cofounder and editor of the online film magazine Reverse Shot, a publication of Museum of the Moving Image; a regular contributor to the Criterion Collection and Film Comment, where he writes the biweekly column Queer and Now and Then; and the author of Terence Davies, published by University of Illinois Press, 2014.