Present Tense: Brett Hanover’s Rukus

Present Tense is a column by Sheila O’Malley that reflects on the intersections of film, literature, art, and culture.

Images from Rukus (Brett Hanover, 2019)

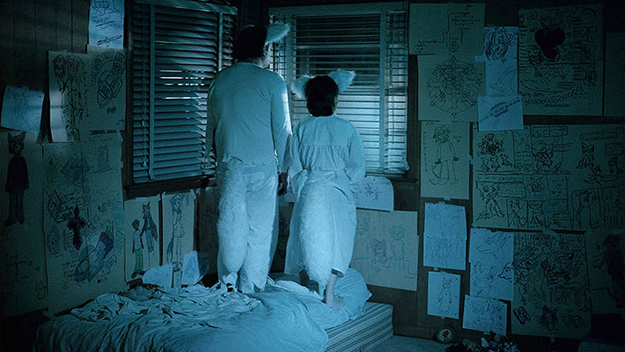

In 2018, I served on a jury at Indie Memphis in the “Hometowners” category, honoring Memphis-area filmmakers. When the jury—Cinereach’s Leah Giblin, film editor Michael Taylor, and I—sat down to vote, we were in unanimous agreement that Brett Hanover’s Rukus should be awarded Best Feature. We admired the film’s merging of documentary and narrative, its scope and emotional power. Hanover’s involvement in the “furry” subculture, and his friendship with an enigmatic figure named Rukus, well known in the subculture, provides opportunities to examine the intersections of dreams and art, identity and community, love and trauma. When Rukus committed suicide in 2008, Hanover began an investigative process, seeking out people in Rukus’ community, his boyfriend and friends, all of whom go under pseudonyms, their avatars in the furry world: “Sable,” “White Wolf,” etc. Through interviews as well as dream-like re-enactments, Hanover strives to discover what drove Rukus, what demons he fought, what alternate universes he inhabited in his head. Hanover dovetails this with a deep dive into his own journey, his struggles with OCD and intimacy, his wrestling with what kind of artist he wanted to be. Through merging these two stories, Rukus creates a contemplative space where the subject itself keeps transforming. Some things, after all, may be unknowable, and the truth usually lies in the spaces in-between.

Hanover grew up in Memphis, and became involved in the micro-budget local filmmaking scene when he was a teenager, following in the footsteps of people like Kentucker Audley and Morgan Jon Fox (Fox appears as himself in Rukus). In high school, Hanover made documentaries about subjects that piqued his interest: Above God, about Gene Ray’s “Time Cube,” and Schiavo, an experimental film about the Terry Schiavo case. (Schiavo screened at the 2005 Indie Memphis Film Festival, and can be viewed on YouTube.) He’s written and directed plays, and collaborates often with Memphis-area experimental filmmakers Katherine Dohan and Alanna Stewart, both of whom worked extensively on Rukus. They all support one another’s projects.

Hanover has chosen to release Rukus online, for free. We spoke about the film over the phone.

It seems to me that Rukus is about transformation. Whether it’s in a costume at a furry convention, or in a romantic relationship or in relationship to yourself—everything’s fluid. Rukus—a star in the furry subculture—says he’s not a furry at all! He won’t claim the label.

That’s exactly it. Everybody is both and neither in the furry fandom. You’re not dressing up as a fictional character like at Comic Con. There’s space for play, very much like early internet culture, in chat rooms and BBSes. There’s also this sense of everyone involved being like, “Well, I am a furry but I’m also not,” or “I was a furry,” or “I’m just here to make a documentary” No one takes ownership. It’s a non-hierarchical community. Obviously there are popular artists but there isn’t a recognized authority or leader. There’s a sense of identifying with it and not identifying with it and holding both of those at the same time.

When did you go to your first furry convention?

2005. They had been around for almost two decades, but it’s a subculture that a lot of people don’t know much about. If you haven’t been exposed to it, it can be very hard to read, and it might seem absurd on the surface. In Rukus, there are scenes where the audience is set up to think: “Oh, we’re going to learn about this subculture now,” but then it’s just people saying, “Well, I kind of am a furry but also not” or “That’s not really furry but it kind of is”. In Rukus you see everything in relation to it, but you aren’t really able to grasp it, whatever it is. That said, I do hope people walk away with a better sense of what furry might be after seeing Rukus.

As far as transformation, yes, it’s one of the biggest themes in the film: this idea of things being located—and the people in the film being always—in between, in places that are temporary or transient, identities bleeding into each other. Within furry, and within some other queer and kinky geek communities, depictions of transformation are a big thing. I have a friend who’s a filmmaker, Lyle Kash, who’s working on a documentary partly about trans men who identify with wolves. I looked through the footage of some of the interviews, and so many of them say stuff like, “I saw a werewolf movie when I was 7…” I don’t deal directly with transgender themes in Rukus but I do think the film is queer in the way it deals with themes of transformation, although not necessarily about gender.

Tell me about the Memphis filmmaking scene you come out of.

When I was in middle school/high school, some people here in Memphis who were a little bit older— Morgan Jon Fox, Kentucker Audley, Eliza Touzeau, Ben Siler—had started a media co-operative, the Memphis Digital Arts Cooperative. It was this place where we all hung out, running around making camcorder movies. The team that made Rukus met around then. I got into documentary in high school as a way of going down wormholes of research. Then, sometime during undergrad in Chicago, that trajectory bottomed out for me. I was asking myself questions like, “Why am I actually doing this? What do I care about saying?” People like Morgan Fox and other filmmakers in Memphis were doing personal video-diary-inspired work, and it was the era of projects like Tarnation. I was very influenced by all that.

There’s such a sense of scope and time in Rukus. How did the film start?

It started in 2008. I had made a documentary [Bunnyland (2008)], and was taking it to film festivals. The reaction I got was often positive but it ended up feeling like I didn’t know why I had made it, other than to get experience making a film. I was questioning what I was doing. Also, that year and the year before, I had a lot going on personally, I was beginning to explore my sexuality, have romantic relationships. In that process, I was making mistakes, hurting people.

Growing up, basically.

Exactly. It all happened very fast for me. I had been in communication with Rukus off and on through 2008. I had had him do this video diary the year before, which we show in the film, but somewhere in the fall of 2008, I talked with him about the changes I’d been going through, and it was the most personal I had ever been with him. It felt like a new stage in our friendship. A few days after that he killed himself.

My immediate response was to archive any trace of him that I could find online. I went through a long process of digging up his LiveJournal, his stuff on Fur Affinity and other forums, his video diaries, 10 years of blog posts, the photographs I’d taken of him, our chat correspondence. I wanted to save all of it because when you know someone so much through online media, when they die, what happens to it? I printed out a huge archive. It filled four large binders. At the same time, I did the same thing with my own archive of material: printed out all my chat correspondences, transcripts from different internet communities I had participated in in the late ’90s, early 2000s, and also every email I had ever written. That winter I went through all of it. I wanted whatever I created to be reflexive, I wanted to position myself in it somehow. I was thinking about it ethically. If I’m going to dig into his life, I’m going to dig into my life, too. It’s only fair. After I finished going through the material, I sketched out an outline that would weave these two stories together somehow. I started shooting the summer of 2009.

You interview Rukus’s friends, his boyfriend Sable, his friend White Wolf. Did you know those people beforehand?

No. Sable got in touch with me after Rukus died. He messaged everybody on Rukus’s contact list. The first thing we shot was the interview with White Wolf. Alanna Stewart and I drove to Fayetteville to meet her. Then I went to Orlando and spent a week with Sable. I had done projects with Rukus, and everybody who knew him was interested in continuing that work. They’re all furries and artists, so everybody was down with the fact that this was going to be an experimental documentary. It got off to a collaborative start immediately. Sable showed me Rukus’s sketchbooks, which I had never seen. The hundreds of drawings added a whole new dimension to the film. It was extremely difficult for Sable. For White Wolf as well. Sable trusted me and trusted what I was doing, but even eight or nine years later, it was difficult for him to see images of Rukus. He didn’t see the film until he came to SXSW and then he saw it with all of us, with a crowd, and he participated in the Q&A, too.

The re-enactments are so crucial. For example, watching Watership Down with your childhood friend: you do the re-enactment with the actual person you shared the experience with, but we just heard her say in an interview that her memories differ from yours. But then you make her act out your version.

I never wanted you to forget you were watching a re-enactment. I wanted that alienation effect. You’re trusting it as a document of something, of some version of these real events, but also as a document of the re-enactment process.

Let’s talk about your main collaborators, Alanna Stewart and Katherine Dohan.

Katherine Dohan, one of the assistant directors, helped write the script and workshop it. Any scene where Alanna and I are on screen, Katherine was the one shooting it. She was there for everything. Alanna and I have collaborated on projects for years. At some point, as teenagers, Alanna and I made an unconscious commitment to keep working with each other and on each other. We’re very different but we’re still collaborating and still best friends.

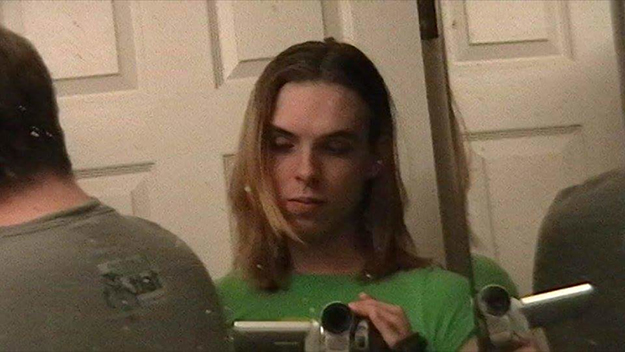

Alanna, with everything else behind the scenes, also plays “Robin.” How did you both think about this relationship in the film?

During some of the making of Rukus, Alanna and I were in an actual relationship, so we were negotiating that, along with making an autobiographical movie. Robin was more than a supporting character. We wanted to make sure her character had agency, and her own inner life, giving the audience a perspective (other than mine) to identify with. I did not want to be an audience surrogate. One thing we wanted to do with the arc of the relationship in the film is to get at some of the bigger themes: intimacy, liminal spaces and play spaces, negotiating consent, porousness, intersubjectivity, love, how people bleed into each other, sexual experimentation, OCD. All those scenes are diagrams of power dynamics and communication patterns, and those diagrams then map onto other scenes.

You’re releasing Rukus online.

Yes. Everyone participating in the film was into the idea of it being public domain, a non-profit project, not just to be respectful of people’s stories, but also because of what the film is about: the way all these artists and ideas float around and link up and transform. I want to see how that happens with the movie. I want it to continue being a living thing.

Sheila O’Malley is a regular film critic for Rogerebert.com and other outlets including The Criterion Collection. Her blog is The Sheila Variations.