On Yasujiro Ozu

An Autumn Afternoon

For years the Japanese had considered Yasujiro Ozu “too Japanese” to be appreciated by the West. Kurosawa and then Mizoguchi were the directors promoted in the West. Donald Richie and Joseph Anderson’s book on Japanese film, originally published in 1959, was the first that most Western film scholars had heard of Ozu. As a result Ozu’s films were not shown in foreign film festivals, museum programs, or repertory theaters. Ozu himself never traveled to the West.

Donald Richie’s book made me curious about Ozu, whose work was not generally available. In the Sixties, each of the major Japanese studios—Toho, Shochiku, Toei and Nikkatsu—had their own theaters in Los Angeles, in which they played their films for Japanese audiences. An Autumn Afternoon was made in 1962 and Ozu died the following year, but the film played in 1969 at the Shochiku in Los Angeles.

I saw it in the afternoon, and it took hold of me. It wouldn’t let go. I wasn’t sure why at the time but later realised it was the same passive-aggressive push pull that drew me to Robert Bresson’s films. Out of that, I developed a theory of a certain cinematic style, a Transcendental Style, and published a book to that effect in 1972.

Ozu’s masterpieces are generally regarded to be Tokyo Story, which usually makes every critic’s Top 10 list, and Late Spring. For me An Autumn Afternoon is among his best. Perhaps because it was in color, perhaps because it was his last, perhaps because it was my first. Whatever.

An Autumn Afternoon

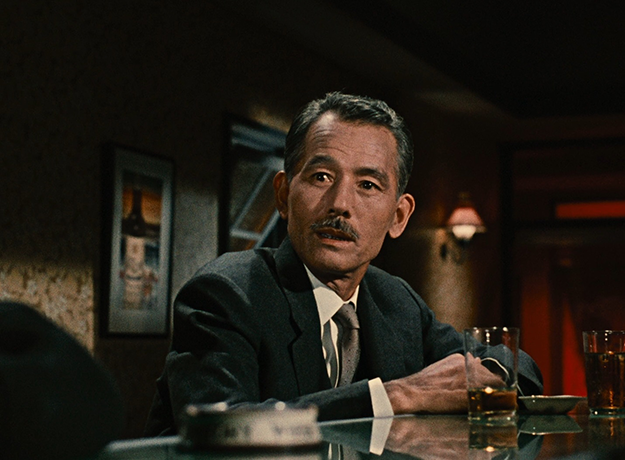

An Autumn Afternoon doesn’t get the attention it deserves because, I think, of the Setsuko Hara effect. Setsuko Hara was one of the great presences of world cinema. She did five films with Ozu—Tokyo Story, Late Spring, Late Autumn, Early Spring, and Tokyo Twilight—and she became associated with his work. An Autumn Afternoon was more or less a remake of Late Spring; it’s the story of a father, a widower, who is losing his daughter. She’s getting married, and he is going to be left alone. In Late Spring, Chishû Ryû plays the father, and Setsuko Hara played the daughter. Fifteen years later, Ozu did a variation of the same story. He used Chishû Ryû again because he was playing the father older than the first version. But there was no way to use Setsuko Hara as the young daughter anymore. So he had to get a new actress, and it was an ingénue named Shima Iwashita. And she did an incredible job. It’s a great movie. But you can’t avoid those comparisons to Setsuko Hara.

An Autumn Afternoon is a reloop of Late Spring. I think it is fair to say that Ozu made the same movie over and over. It’s like the Torii in the Japanese temple, which is the gate painted in reddish orange (the color shu). The Torii all look very old, but every 100 years or so, they take it down and put a new one up. The important thing isn’t its being old. The important thing is the form, the structure. So just because you made a movie 15 years ago doesn’t mean you shouldn’t make it again now. And basically he is making the same movie. It’s interesting to see Chishū Ryū in both movies, because in the first film he’s playing a certain age, and in the second one he is that age.

Look at this scene from Late Spring, the earlier version.

So as you see, Setsuko Hara was a tough act to follow for this young actress who essentially had to slip into that same role.

Ozu had a few actors who really were right for him, and he tried to keep them as long as he could. He would do a lot of takes, wearing his actors down. These were actors who were in other motion pictures, acting for other directors, and Ozu had to take them back to their essence. Bresson dealt with non-actors and he would instruct them: “Say it rote, say it rote.” It’s harder to do that with a professional actor who knows how to make a line mean something more. And in that case you just have to do it over and over and over again until finally, you get them to the level where you think they should be. But also, if you have actors who’ve worked with you before, they know what’s coming. They know what’s expected of them. Chishū Ryū gave the same performance for Ozu for 30 years.

In Transcendental Style in Film: Ozu, Bresson, Dreyer, I compare Ozu with Bresson. They are both minimalists, and they are both concerned with the Other. But East is East and West is West. You can’t go too far in comparing them before you run into some contradictions. Shinto and Christianity present such different concepts of the Wholly Other, you have to almost step back from culture to see that they’re really alike. Christian transcendence implies sacrifice, redemption, transformation. Whereas in Shintoism, the concept of the transcendental implies acceptance emerging.

So films evoking the Other in these opposing cultures will have to be different. If you compare Martin LaSalle (the young man in Bresson’s Pickpocket) with Setsuko Hara, a lot of what’s going on is the same. It’s the same physical attitude. The same restrained emotion. The same cutting pattern. But one is Eastern, and one is Western, I guess. And I think Bresson felt that he had to push you away even further, whereas with Ozu he was working from a tradition of pushing people away. And as Ozu said about an earlier film, Late Autumn: “People complicate the simplest things. Life, which seems complex, suddenly reveals itself as very simple. I wanted to show that in this film. There was something else, too. If needing to show drama in a film, the actors laugh or cry. But this is only explanation. A director can really show what he wants without resorting to an appeal to the emotions. I want to make people feel without resorting to drama. And it’s very difficult. In Late Autumn, I think I was really successful. But the results are still far from perfect.”

This may sound familiar. It sounds very much like Bresson. They both understand the power of withholding. And it is tricky with Bresson because there’s a thin line you have to walk when you’re pushing the audience away while you want them to come toward you. It’s not unlike the power of withholding in any relationship. Playing hard to get or unfeeling may make you seem kind of mysterious and intriguing to people, but it also may drive them away. And so you have to learn how to withhold something in a way that makes the other person really want to come toward you, and in movies it’s not much different.

Late Spring

Ozu’s films don’t have villains per se. Some of his characters are selfish, but the “selfishness” is treated as kindness. In the clip we watched from Late Spring, Setsuko Hara says, “I just want it to stay this way.” The sentiment is treacle—basically “I love you, father, and I never want to leave you”—but Ozu plays it for pathos. Similarly with her line, “Why must I get married?” There’s a complexity to it.

Ozu directed 64 films from 1927 to 1962. He started out in comedy. A couple of fortunate things happened to him during his career. The first was that he’d gotten into the Shochiku studio. It was relatively easy to get into the movie business at that time because it was a disreputable business. He got into the Shochiku jidaigeki unit—jidaigeki meaning period films, costume dramas. And just as he was going to start working there, Shochiku moved the whole jidaigeki unit to Kyoto. I have a feeling that if Ozu had started out making costume dramas, he’d have never ended up where he did. He was assigned films about common life called gendaigeki. He began his career in comedy. His mentor was a director who specialized in nonsense-mono, which was a series of slapstick routines tied together by some kind of plot—the basic appeal of silent movies. But as Ozu’s career continued, he pared the comedy down, and eventually ended up in shomingeki, which are movies about the family.

In the ’30s, his films started getting a little darker. It wasn’t primarily because of a social consciousness—it was the worldwide depression, the growing militarism, and the sense of unease that pushed his films a shade darker. The first film that shows the signature Ozu characteristics was Tokyo Chorus in 1931. Take a look at this clip from Passing Fancy, a few years later where the pieces are sort of there, but it takes him a while—decades in fact—to figure out exactly how the pieces work together. You can see the man who began in slapstick, doing fart jokes and all that kind of stuff, slowly evolving into another director.

Ozu spent most of World War II trying to figure out how not to make films. He was part of the war effort. He was assigned to the filmmaking unit and didn’t have to serve in battle, so he expended his efforts writing scripts that never got finished and ideas that ultimately never worked out. He shot one film that was so boring that nobody wanted to see it. Ozu didn’t want to do the propaganda films, but eventually did one. He was smart enough to burn it before the end of the war, so he avoided those humiliating trials that others artists went through.

While doing a kind of documentary about Japanese conquests in Shanghai, he stumbled onto the American films that the British had stored in Shanghai. And he didn’t have much to do, so he screened these films over and over. He said he watched Citizen Kane a dozen times. He talked about watching Rebecca, The Little Foxes, Fantasia, Tobacco Road, Stagecoach, How Green Was My Valley. Because he talked about them so much, a number of critics have sought to figure out how these American films influenced his style. The general consensus is that seeing all these films didn’t influence his style one bit! The only thing that changed after the war was a little more aestheticism, a little more attention to the physical beauty of objects. But he took nothing from the West.

The war had a fortunate effect on Ozu’s career. Before the war, he was becoming less and less in favor because of the darkness of his films. When he began anew after the war, his mood matched the postwar mood. The sadness and the melancholy and the ruminating of his films was no longer so uncommercial.

Ozu is often called the most Japanese of all directors, but he’s really unique even in Japan. He’s not the most Japanese of all directors. He is what the Japanese would like to think is the most Japanese of all directors. Look at the titles of his films. The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice. Talk about subtlety. What exactly is the flavor of green tea over rice? It’s not salsa! The Japanese title of this film, An Autumn Afternoon, which was changed for American release, was The Taste of Pacific Saury, which is a type of mackerel, a very flavorless fish, served in autumn. This was his title. There would be no reference to mackerel or eating a fish in the film. The movie itself was meant to convey the subtle taste of saury.

The Flavor of Green Tea Over Rice

Critics talk about his camera placement, how it’s at eye level if you’re sitting on the floor. But Ozu will shoot an office scene, where everybody is standing or seated in chairs, at that same height. So I think it’s not so much about the eyeline of a person sitting on a tatami mat; it’s about lack of freedom—restricting yourself. In Passing Fancy, he was moving the camera; he was actually dollying. He continued to make films and realized, “I don’t need to dolly.” So rather than this being a “Japanese angle,” it’s just about the whole idea of finding freedom in stricture and in withholding. It’s not dissimilar from what a person in a monastery would say: it’s only through this type of ritual, only through this ascetic life, that I can actually feel free.

Occasionally Ozu pays a price for his restraint. He gets trapped in a low angle and a character doing a golf swing is cutoff at the elbows. Or, in the American way of editing, you play a lot of dialogue off screen while intercutting reaction shots. Ozu plays most of the spoken lines on screen. He’ll still have the reaction shots, he just won’t have them with dialogue.

He hated to change things, so although the first Japanese talkie was made in 1931, Ozu didn’t make his first until 1936. He continued to make silent films for five years while others did talkies. It was strange because his films were full of dialogue. That’s an enormous amount of dialogue for a silent film audience to read. You’d think that a guy who’s having to put so much of his dialogue on cards would just love the chance to have sound. But he didn’t like to change and came to sound very, very slowly.

The same thing with color. Ozu came to color reluctantly and not until 1958. Bresson was also reluctant to use color, and, in fact, Bresson’s use of color was not particularly inspired. But Ozu’s use of color is extraordinary. With Ozu, there is the feeling that the shading of every color is precise and calculated—there is no randomness in the film. Color knocked everything up a notch for Ozu: his aesthetics, but also his asceticism, were better revealed in color. And you can only attribute this to his predilection to refine rather than innovate, you know? Western directors—they’re always talking about new ideas, new concepts, and with Ozu it was always, “How can we do it over again a little better this time?” Repeat and improve, repeat and improve.

One interesting aspect of Ozu was his signature love of objects and the placing of objects. He had a propensity for foreground objects. The phone or the ashtray or the bottles. And when he cut back and forth, they all jumped, because he’d have them on the other side. There is a lot of intercutting with men sitting on tatami at a low table, drinking sake, and he will always place foreground objects in front of them, which normally isn’t done, because it makes the objects appear to jump. That, of course, comes from a meticulous Japanese character trait, which you see in flower arranging and gardening and all the other various tactile arts that they do. And the compositions are so similar in some of those setups that it seemed that only the background changed, because it’s the same guy doing the same thing, only now you have the opposite background!

Ozu’s Japanese affinity for arranging objects also speaks to the so-called “pillow shots.” A pillow shot is really just a still life, a cutaway to an object. His favorites are trains, laundry, a tea kettle, factories—usually in a triad, boom, boom, boom, and usually with music. And this creates a tension between the changing moment and the unchanging world in which the characters live. There’s a very interesting pillow shot in An Autumn Afternoon when he cuts to a ballpark. You hear the crowd yelling, and he just cuts to the huge stands of lights that are illuminating the field at night, boom, boom. And the next cut is to the game, only the game is on a TV in a bar. The characters are watching the game. So he bridges one exterior to another with this very careful compositions of lights, when none of the characters are even at that location.

The term pillow shot was neither coined nor used by Ozu. Several years after his death, a Japanese journalist compared them to the pillow words which are found in traditional Japanese poetry. These are short poetic pauses that appear between longer stretches of poetry. The critic Noel Burch wrote a book on Ozu, and he coined the term pillow shot, and that phrase stuck. Ozu is using these pillow shots for essentially the same purpose as the pillow words in poetry. And he worked wonders with them. He casts a spell over you with them.

An Autumn Afternoon

His films were very tightly scripted; he and writer Kogo Noda worked together from the silent era to the end of his life. They would go to an inn somewhere and drink and write. An Autumn Afternoon ends with a wedding. In the West, the wedding would be the payoff. Here there is no wedding. It goes back to Ozu’s quote: “It is easy to show drama in a film, but this is only explanation. A director can really show what he wants without an appeal to the emotions.” Ozu is not giving you the drama you want but giving you the drama he wants, which is the drama of style. It’s almost musical the way those inner cuts occur, and those pillow shots—the way they roll out, boom, boom, boom. Almost mathematical, almost like the equivalent of trance music: the scene is coming to an end now, the music will come now, and then we’ll see the big wide shot, and then we’ll see some laundry, and then we’ll see a train, and then we’ll see a person walking down an alley, and then we’ll get a new location.

The music is very sentimental. And it’s used for codas; there’s very little underscoring, where music drifts under a scene while characters talk. Instead, it’s overscoring, where music dominates the scene, and it goes with those pillow shots and creates the codas. Not dissimilar to what Bresson does with the music in Pickpocket and A Man Escaped. No music at all during the scenes, then a coda appears without dialogue accompanied by a dramatic overscore. Ozu does no underscoring unless it’s source music, because when he wants to use music, he wants it to be music—to be its own fully stated emotion. And for this he uses very sentimental music, Western sentimental tunes.

He overscores to maximize a kind of fullness of emotion, but he’s also doing some to say: “In the rest of the world, nobody cares.” These three people in this house are going through a heartbreaking moment, but that woman is washing her laundry while the train passes, and the music fills the screen—they’re all coexisting in the same world. It creates a tension between the eternal, the permanent, and the immediate.

An Autumn Afternoon

An Autumn Afternoon is Ozu’s final film. He was only 60 at the time. He didn’t know he was sick at the time. He had written the next one, and they were getting ready to shoot when he got cancer. Ozu was only 60 but I think he was already feeling as old as his lead character. You might think from the type of films he was making at the end that he must have thought his end was close at hand.

You might also think that a director who made films with so much warmth, whose work is infused with such happiness and sorrow, must have had a contented life. The opposite was true. He was a chain-smoker, he was an alcoholic, he lived with his mother. His mother died about six months before he did. He never married, never had children. He lived for the cinema, and all he did was cinema. He didn’t really have any other life. He had a morbid cast of mind. On his tombstone he had a single Japanese kanji inscribed on it, and that kanji is mu, which means “the void” or “emptiness.” You can look at his whole filmmaking career as one slow fade-out. A dissolve against a static shot where finally he’s gone, and he’s in that Zen land of mu.

When I first saw An Autumn Afternoon, it didn’t really knock me out in the way that other films did, but I couldn’t get it out of my head. I couldn’t figure out how it worked: the camera never moves, the compositions are the same, the person is the same size and looking right at the camera. But Ozu is able to create that rhythm. And again, like Bresson, it comes down to style. Movies are antagonistic to articulating spiritual feelings, but through a process, a stylistic ritual in motion pictures you can create a feeling of transcendence or a sensation of the Wholly Other.

This article follows Paul Schrader’s series of lectures on filmmaking, shifting focus to “Films Which Changed Me.” Schrader’s latest film, Dog Eat Dog, is in theaters now.

Paul Schrader is a screenwriter and director of 19 films to date. He has been contributing to Film Comment for over 40 years.