NYFF Interview: James N. Kienitz Wilkins

Among the many notable facets of James N. Kienitz Wilkins’s films is the fascinating way in which thought plays out on (and, sometimes, off) screen. It’s something of a cliché to say that a filmmaker uses the camera as an instrument for intellectual investigation, but Wilkins goes about it with an ever-shifting style and constellation of concerns that are quite specific to him and the broader culture that his films engage with.

Wilkins, 33, is the rare experimentalist who takes a noticeable interest in writing, especially screenwriting but also detective fiction, confessional monologues, interviews, elevator pitches, and Powerpoint presentations. A former Cooper Union classmate of kindred filmmakers Gabriel Abrantes and Alexander Carver, the Maine native co-wrote the screenplay for the forthcoming follow-up to the much-lauded Fort Buchanan (15) directed by Benjamin Crotty. He is a canny conceptualist who explores race, Hollywood, the Internet, and a host of other subjects with wit, daring and a knack for demonstrating how the various fixtures of our historical moment that we take for granted are in fact strange, funny, and worthy of further examination.

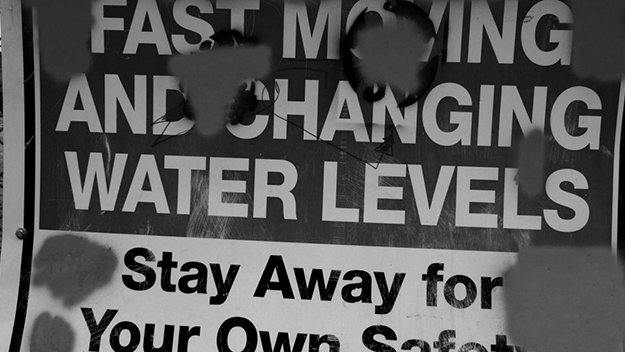

The script for Wilkins’s Public Hearing (12) was sourced from a publicly available .pdf of a transcript of a hearing conducted in Allegany, New York, concerning a local Walmart’s proposal to become a “Super” Walmart. Indeed, found material and technologies proliferate in his films, from the scrap-heap-bound Mini-DV camera with which he shot the first short in his Andre Trilogy, the interview-based dream exploration Special Features (14); to the mysterious tape that comprises the bulk of the imagery in the postmodern gumshoe yarn Tester (15).

The recipient of this year’s Kazuko Trust Award in recognition of the excellence and innovation of his moving-image work, Wilkins will present his latest, Indefinite Pitch, on October 8 and 9 in Program 5 (“Site and Sound”) of Projections at the 54th New York Film Festival. Film Comment sat down with Wilkins on the eve of NYFF54 to discuss his practice, the road he has taken to get here, and how his filmmaking relates to our increasingly bizarre present.

Indefinite Pitch

The concept of Indefinite Pitch hinges in part on the appropriation of a traditional form or structure that’s very familiar to audiences—in this case, a Powerpoint presentation. You’ve played with this type of gesture before, with detective fiction (Tester), a transcript of a public hearing (Public Hearing), found footage, etc. I’m wondering what attracts you to this kind of material, and at what stage does it enter into the work? I’d imagine that it’s often there from the beginning, but perhaps at other times you realize at some point along the way that you want to take it there.

I think that all of those forms are effective. A Powerpoint presentation is effective in doing what it tries to do: convince corporate guys that this product needs to be improved or something. Or detective fiction as we’re familiar with it, like a mystery novel or a noir, works already, so I’m attracted to what works. But at the same time, I’m very intent on trying not to do something new but just do something that’s unique to my situation. In Q&As I sometimes talk a little bit about Hollywood, and I sense that some avant-garde purists find it tacky to even say the word in that space. But I feel that’s disingenuous, because we’re so affected by these preexisting forms around us, be it big blockbuster movies, mystery novels, corporate culture, Coca Cola, whatever. And I guess I’m trying to figure out how to deal with being in a world of products but not make something which is itself a product or which can be easily categorized as a product. And I don’t think it necessarily entails a complete rejection of the product, just critically rethinking it.

That’s kind of vague, but I’ve been thinking a lot lately about the distinction between product and non-product. This seems to me to be a more important battle than some of these other supposed battles we’re dealing with in cinema, like fiction versus nonfiction, which seems so besides the point. How to deal with this consumer culture we’re in, and recognizing what works about it without being its pawn.

Do you think you’re now moving toward making films that are unmistakably these non-products or anti-products, whereas before you were thinking about it differently, or has this always been the case?

I’d say it’s more so moving in that direction. But I’ve always had this inclination. I think I just made some mistakes of youth with some earlier projects, especially stuff I haven’t really shown people, where I would get like 75 percent there and then not question certain realities about distribution and actual expectations and how this thing is going to function in a market. And I’m not saying I’m better at that now, rather I’m learning how to reject certain things, like getting into Sundance, predicating a movie on blowing it up to 35mm or something like that, which is something that 10 years ago I would have thought was cool. And it comes out of definite experiences, like trying to make money, not having money, trying to make money within the art world, within the film world, having actually done pitches.

When I was 21, I was a script reader for this small production company that was run by the son of a very famous fashion designer. They had produced—and this is fucking ridiculous—a really shitty black Great Gatsby set in the Hamptons. And I came on right when that was finished, and I saw it. So they thought it was going to be this big success, but it didn’t make even a ripple. Because it was a fiction, it was such a social fiction. They were trying to take advantage of the Vice-style coolness of, “Imagine these rich hip-hop black people in the Hamptons.” It was like a music video, but then it’s also supposed to be this social commentary, and it just didn’t work because it was imbalanced and uninformed.

But then they were ultimately, like any cultural institution, sort of predatory towards young people. Free labor, plus lots of energy and ideas. They had me read books and scripts and rate them. One book that came in was a collection of Cornell Woolrich’s noir stories, which I really enjoyed, and I had an idea for a script that I could write about one of them. I ended up pitching it to them. It was the first and last time I’ve had a real pitch for a fiction film. It was so funny, because I was so young, and they were like, “Cool, cool.” And they gave me an honorarium to buy research material, and they actually expected me to write a screenplay in a month. But I was a sophomore in college, and dealing with school. I had never written a fully successful, completed screenplay. And I sort of had a freak-out, I just stopped talking to them. But then in hindsight, I realized, “Oh, this is really interesting—if I had completed it, I would basically have given them free material.” They would have probably even, due to some sort of clause that I was unaware of, owned what I had written. And I was just like, “Man, the system is so predatory.” And it’s so product-oriented. I was also incompetent due to my age.

I guess, looking back on it, the only thing that we can rely on is our ideas. Even in legal culture, ideas can’t be copyrighted, only the expression of ideas. Once it’s written down, that’s what’s copyright-able. And that’s why with Home Alone 2 [11], I was really interested in picking that title. Because legally, you can do that, so why not? And knowing that once it exists and it’s cross-referenced and conflated on the Internet, it will confuse things. It’s gotten to the point where I actually looked up my name recently and there was this weird aggregate website of TV listings, and it said, “10:00 a.m. Home Alone 2. Directed by James N. Kienitz Wilkins. Starring Macaulay Culkin, Joe Pesci.” And it had the poster. Information is so bad out there now, it’s just eating itself alive. Especially these aggregate sites. They’re so parasitical, these clickbait sites. Robots take information and add some new stuff, this bizarre Frankenstein-ing. Anticipating that, though, is really interesting to me.

Public Hearing

I’d like to get back to talking about scriptwriting and pitches. Among the relatively recent or emerging crop of international avant-garde filmmakers, your work stands out for having a really pronounced literary dimension, or engaging very explicitly with the phenomenon of writing. Do you have any thoughts on what the place of literature, but specifically screenwriting, is within your project?

Thank you for noticing that. I think the written words—language, I should say—is of utmost importance to me. I love movies and I can enjoy pretty much any movie and always have. It’s what I feel best at, but that doesn’t mean that’s necessarily what I think is most important. It sounds a bit coy to say that I think that making movies is easy, which it’s not. It’s very labor-intensive, but it’s a different type of labor. For me, it comes easier than, say, writing a novel. If there’s a hierarchy of art forms, the novel is at the top, and then movies are just where I’m able to exist due to my limited skill set. I’m always flummoxed when people still, to this day, are like, “Movies are a visual art.” It’s been proven again and again and again that beautiful images can be created. So why are we still obsessing over that as the end goal?

Also, beautiful images are more easily rendered as products or capitalized off of than intelligent writing.

Exactly. You know the adage or piece of advice they teach in film school, or I’ve read in books about screenwriting: “Show, don’t tell.” And that’s actually said a lot in relation to writing, too. But I think it’s interesting to actually state what you’re doing, and then to almost make it so obvious that you have to move beyond it. Then it starts to become poetic again, instead of trying to start from a place of obfuscation and poetry and feeling. Just being like, “I am feeling this, I think I’m feeling this because…” It’s analytical, it’s intellectual. But I don’t think it excludes the world of feeling and beauty and all these things. Literally stating things is really exciting to me. You can never actually state reality. It’s always allusive. That, to me, is such an obvious truth. There’s no risk in stating something.

In a lot of your films you deliberately try to slip out of the position whereby you would have to present conventionally beautiful images. They’re often very nice images, like in Indefinite Pitch, but the action of that film is in the voiceover rather than what’s happening on screen. Your most traditionally, recognizably cinematic film is Public Hearing, which, if one were to treat it on a primarily visual level, one would miss the joke or prank that’s unfolding across its two hours.

I think it’s interesting that you used the word “joke,” because jokes are told for the most part. A joke is something that’s told between people and there’s supporting material that aids the joke, but for the most part it’s on the level of language.

I can’t think of anyone else currently who approaches cinema in this way, though—someone who says, plainly, that cinema is about ideas.

It is. I’m sometimes confused when people don’t look at it that way. There are so many competent, rich people out there who can make really beautiful, interesting, investigative dramas. I’m not even going to try to compete on that level. For me, reading is really important, and writing, the dictionary, and Wikipedia. I do feel lucky to be a filmmaker in the age of the Internet, because it makes things easier for someone who’s not predisposed to go out and schmooze and try to raise money for grand ideas. That would be really hard for me if there wasn’t this access, this self-education tool, which is not just about the history of cinema and its techniques and tools, but also about words and language. Constantly cross-referencing things and increasing my own education plays a big role.

B-Roll with Andre

How did the Andre Trilogy come about and how did you transition from that to Indefinite Pitch? Some of the strategies in Indefinite Pitch will be familiar to those who saw the three Andre films, but then it’s also quite distinct aesthetically.

I’ve been realizing as I make more work that I think beyond the individual piece and how pieces might fit into groupings. It’s important to me to work on multiple projects at the same time, and as a result, groupings form. Special Features really grew organically. I was surprised by how well that one came off, because it was truly an experiment. I wrote the monologue and—unlike Public Hearing, which took six years to raise money for and was so stressful and expensive—I was using throwaway gear from a major TV news station that was discarding Mini-DV tapes and cameras. That was super-exciting and so generative for me. It started out as a dream, which inspired the monologue, and then everything came together for the piece, and then the fact that the piece worked as well as it did just put me on a tear. Then with Tester, it was a tape that came on a deck I acquired, and then B-Roll with Andre [15]… they all connect to personal experiences to a certain degree, and learning to be okay with how the personal integrates with art is something that I started to get comfortable with after Public Hearing.

Technology is very central to the entire Andre trilogy. Throughout it you use particular information- and filmmaking technologies, and the films take on a self-reflexive, archeological aspect insofar as they become films about the technologies used to make them. Do you think about it in those terms?

I do think about what it means to be contemporary, the question of why I am making something now with these tools. What is it about making a movie now? There is a kind of self-documentation of my personal circumstance: we’re all alive right now, we’re here, we’re living our lives together, and things like Panera Bread and Dunkin’ Donuts and USB sticks are parts of that. It’s funny, but these are our lives and there’s no avoiding it. Movies traffic in time but they are also mechanisms for marking time, like clocks. You can tell time by them if they’re made properly. That to me is really powerful, and if you view them that way, then they must be self-reflexive. Like, “Yeah, I want to shoot this sexy actress… but apart from my attraction to her, I’m waving this type of camera in her face.”

What you’re saying about technology touches on the notion of baring the device. I read some interviews you did around the time of Public Hearing where you talk about Brecht a lot. In a way, the baring of the device in your work has only intensified since then, but in a funkier way than people might expect from the more classical Brechtianism of Public Hearing, where there are prompts within the film for the spectators to reflect upon themselves as spectators. It made me curious about how you see your relationship with the spectator now.

It is different… Public Hearing is five years old now. It was conceived five years before that, so it’s a 10-year-old idea in a sense. I just read Brecht’s The Caucasian Chalk Circle recently. I really enjoyed it. It was actually a nice yarn. It’s so concise. It’s amazing how the scenes just do what they need to do and he actually talks about just stating what is necessary. It doesn’t mean the ideas are simple at all. It’s almost like he’s using words in the way that one would use the physical materials available in a studio. But Public Hearing is also, by design, not a personal film. Its prank is what it is about, and you’re either into that or not. I think the newer stuff is more personal, that’s the big thing for me.

Indefinite Pitch

Then, are you as concerned with the effects you achieve on the spectator now?

Yes. I know what I’m doing, or at least I think I know what I’m doing. I’m my own best test audience. If something works for me and gives me a certain type of pleasure, I think I have a pretty good sense whether it’s going to work for at least a few other people. I’m not interested in making movies that are purposely trying to be smarter than the spectator. Public Hearing maybe teeters a little on the I-know-something-you-don’t-know, just in terms of the reenactments and the source material. The newer films are a little more generous, I hope.

I really love the conventional rules that are taught in film school, like shot/reverse-shot, reasons why we look at certain relationships between characters as such. I’m always aware of how that stuff is used in combination, so there are always two things happening in any movie: the narrative perspective and the intellectual perspective which looks at how the movie is constructed. I like the idea that those things are in tension rather than one dominating the other, which usually happens in mainstream movies. It happens in novels, too. I read a really bad novel that was recommended by James Baldwin in an essay he wrote. It’s a totally crazy book. There’s a moment when everything is cruising along and you are used to the main character’s perspective where you’re able to get into his head and that’s all fine… but then—randomly, I felt—when it was convenient plot-wise he jumps inside this police officer’s head, so you can hear what this guy thinks, and it wasn’t handled well. It was just a very convenient movement to convey a point that was necessary to push the plot forward. Shots in films do that all the time. I’m constantly thinking about that, how we take advantage of cheats, and how to create something that’s consistent with itself.

Your work has explored various kinds of cinema, from your engagement with Frederick Wiseman and cinema verité or even with David Fincher’s Gone Girl, which figures prominently in B-Roll with Andre. What your films do with race is also connected to the film industry: in B-Roll with Andre, Gone Girl is dismissed as being the “whitest film noir,” and at the end of Special Features the subject asks you where the film will be shown and you start talking about its possible distribution and how it might play in France because French people have an exoticist fascination with American black people. How do you think race fits into your work?

Race is always an issue, but it’s been huge one in these last few years for everybody. I’m not any less immune, and I’ve definitely been thinking more about race, my own race, being mixed-raced and having grown up in a state [Maine] that is 90 percent white. Indefinite Pitch talks about that and what it means, even for me, to engage with people of different races and what those expectations are and whether it’s easier for me or harder. And how it affects my own ambitions for making films, writing scripts… It’s pretty startling how a screenplay never has to specify that a character is white.

Like how, in conversation, if a white person refers to a black person, inevitably they specify that the person they’re referring to is black.

I’m not offended or touchy about it. It’s just that if I begin to think about it, where do I fall personally? If someone needs to describe me in those ways or is writing a screenplay that involves me, how would it affect casting decisions or the way it’s read? If we don’t define it early on, the neutral state is basically just white. Does that mean, as with the script that Benjamin Crotty and I wrote, that an emotive coming-of-age experience is by default white and you would have to add some kind of stereotypical funk or flare to make it black? Because obviously there are so many different types of black people out there. I think the reason that race comes up a lot in my work, like technology, writing, being broke, is because that’s me. It’s me creating characterizations out of concerns in my life. I’m tired of trying to hide that stuff or create a fantasy world that is sexier than reality. I’m happy that people are watching my movies, and it’s really nice to receive the Kazuko Trust Award, but I’m not trying to trick anyone into thinking that I lead a glamorous life.

Dan Sullivan is the assistant programmer at the Film Society of Lincoln Center.