NYFF Interview: Ben Rivers

With a title that suggests the epic and primeval, The Sky Trembles and the Earth is Afraid and the Two Eyes Are Not Brothers feels like a departure from Ben Rivers’s previous films about man, nature, and cinema. In its first incarnation as The Two Eyes Are Not Brothers—an installation inside the BBC’s now-defunct Television Centre in White City—Rivers projected assorted images onto disused sets: Oliver Laxe and Shezad Dawood shooting their own films (Las Mimosas and Towards the Possible Film, respectively) in rural Morocco and the Atlas Mountains, a landscape also littered with various abandoned sets; author Mohammed Mrabet telling stories to the camera; and a dramatization of Paul Bowles’s 1947 short story “A Distant Episode” in which Laxe plays the Westerner protagonist who is abducted by bandits, de-tongued, and transformed into a kind of feral clown decked out in a suit made of tin cans.

In the feature-film version, the story is streamlined down to Laxe’s shoot and his character’s capture and decline. Shooting in exquisite color 16mm, Rivers captures the blistering tones of Morocco’s deserts and the repetitive banalities of being on a set, in his characteristically hypnotic, unhurried visual style. He slowly draws out the menace within a Western gaze—and what happens when its violence is returned. Reminiscent of Pere Portabella’s otherworldly Vampir Cuadecuc (shot on the set of Jesus Franco’s Count Dracula) in tone and approach, The Sky Trembles… screens on October 4 in Projections at The New York Film Festival. FILM COMMENT spoke to Rivers over the phone earlier this week.

Prior to this, your films have focused on the more liberating, or positive, aspects of nature. The Bowles story, which the second half of the film is based on, is very much about the punishing aspects of nature and intractable difference. What drew you to this story in particular?

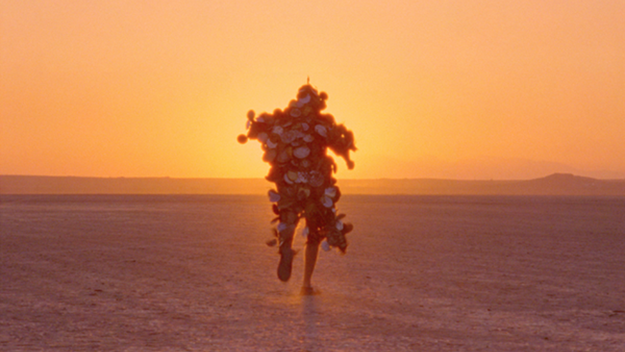

That’s a really good point. I think that was one of the draws, in a way. In a lot of Paul Bowles’s stories based in Morocco, there’s this extreme allure of the desert; it’s extremely beautiful and enticing. But at the same time, it’s so inhospitable—it’s hard, it’s hot, it’s sweaty. It’s this kind of double-edged aspect of the landscape that I too found really exciting. It’s much less familiar to me than the forests and mountains and lakes, these kinds of places where I do feel much more comfortable. So I think that was something I kept coming back to with Bowles, this relationship to landscape and also being an outsider in that landscape, somebody who’s really not from that place. Bowles tries to deal with that in his writing, and I was interested in dealing with that as a filmmaker. What that means, to be a filmmaker who’s outside of the comfort zone. There were other things that I found—I read the story probably five or six years ago, and it kept coming back to me in dreams and daydreams. It’s very much like that, like a fever dream. In particular, the final image of this tin can man running into the desert, towards the sun, seemed like such a powerful image to me that I couldn’t get it out of my mind and I really had to do something with it. And then it was a roundabout way that I arrived at how I could deal with it. I wasn’t really interested in doing a straightforward adaptation.

The story is very unsettling. To talk about the ending for a little bit: the professor in the short story definitely brings this fate upon himself, and now it’s easy to say that what the professor was doing was this very Orientalist, racist thing. The filmmaker in your film also brings it upon himself, but what he’s doing isn’t as nearly as odious.

He’s a much nicer person. In a way it’s much more complicated. If you take Oliver as an actual filmmaker living in the world, he’s really invested in that country. He’s lived there for almost a decade. He has converted to Islam, and he speaks the language fluently. Really, it’s his second home. It is more complicated but at the same time there’s still this question or this statement that the bandit first says, when he’s first dressed, that he’s been circling around trouble. He’s been looking for something.

And he’s found it.

And he’s found it! You could say that the punishment is too great. I mean, it is really hard. But at the same time, it’s a danger that he has circled around and I wouldn’t necessarily say that he deserves it, but it’s a possibility. And it’s not to do with—somebody said: “Oh, it makes Moroccans seem like something to be feared.” But I think that’s also a Western, preconceived perception of the viewer. That actually, you know, it’s just humans that need to be feared, and those humans can happen anywhere in the world, in the same way that the film is full of a love of the place. I think that even though these four bandits are really cruel, I also tried to film them with love and show them as humans, as people who sing and laugh and sleep. In the end, he’s going toward, most likely, a certain death. But I wanted the end to be euphoric in a way.

It’s the same as the end of the [Bowles] story. He’s completely lost his sense of self—who he is, his whole ego and everything. Getting a reminder of who he once was sends him mad, but it also gives him freedom. So even though he could be running to his death, it’s by his own choosing. I wanted to use a long lens to flatten the plane; it almost looks like he’s running back towards the camera sometimes. So something’s changed optically, it’s what happens. That shot, I did it a number of times in Morocco and wasn’t happy with it. In the end, that’s the only shot that wasn’t shot in Morocco. It was shot in California. On a dry lake called Mirage Lake, which I thought was really appropriate. It’s called Mirage Lake! It makes complete sense with the rest of the film, that it’s a kind of illusion.

It’s so stunning. The colors are just incredible. The ending, however, is very slightly different, because, again, time has passed since Bowles wrote his story—in the original he passes by two French policemen and they assume that he’s Moroccan, some devout tribal guy instead of a Frenchman like them.

Like a Holy Fool kind of character.

Right. What did you consider when you were adapting it, given that the type of colonialism of Bowles’s era is long over? In some ways, I think your adaptation is a lot richer because of the performative aspects of his punishment and actually seeing the reflective tin can suit.

It’s obviously really changed a lot because of this whole first part of the film, which already shatters his kind of construction and you’re not really sure… Some of the parts in that first part are also set up and then in the second part, which is entirely set up, also has three improvised moments. But yeah, in the original story, in a way, it’s fairly black and white what he’s doing, and is based very clearly on this colonial history. Of course, Morocco has moved beyond that, and hopefully people who work there from the outside have also changed. Still, as a filmmaker going to work in other countries, you still have to ask that question like “Why are you there?” I think you just have to be aware of yourself and your position. Bowles was definitely aware of this, and it’s really amazing that he would write these stories [in the 1940s] which were really confronting the colonial figure. He was also completely invested in the country, knew it inside out, and lived in Tangiers for decades. I think he’s also really smart in the way he plays with the problematic of his white characters.

I tried really hard to get the essence, the kind of hallucinogenic feeling of that travel. I shot so much more of the bandits and Oliver traveling. You don’t really need that; screen time is so different. But I really wanted to get this kind of unrelenting feeling of moving through this crazy landscape. And for it to be, as I said earlier, like a fever dream. I like that idea, something that feels like it’s never gonna end. But it’s funny because when it does end it’s really banal. It just comes down to, like, commerce. Just exchange of money. I was really happy with the bit in the story where he looks at the calendar and then in the film, we had all these DVDs in that room of Moroccan TV, and soap operas, and films, and we even had some rushes from Oliver’s films, which was just way too meta. But in between, when we were trying out different DVDs and setting up shots and stuff, this classic bouncing DVD logo came up, and of course that’s what we should use. It was such a beautiful gift, which I’m always looking for, in the world.

Screensavers are intentionally trance-like, too. Speaking of Paul Bowles and his legacy: I understand that the installation had Mohammed Mrabet telling stories to the camera, and footage from the set of Shezad Dawood’s film. Why did you decide to take those out for the feature?

Well, I always knew that the two things were going to be really quite different. Originally I thought that Shezad’s film was going to be a sort of prologue, and I was going to integrate Mrabet into the feature somehow. In these little films he’s sitting next to Shakib, who is the main actor in Oliver’s films, so the idea was that it would look like Shakib had wandered off set and had sat down next to Mrabet. But with both things I tried to make them work in the edit and neither of them sat properly. Which was a shame, I guess… but not so much because I knew I was also doing the installation and the installation was always going to be more fragmented, a more exploded version of the whole project. So yeah, there’s the behind the scenes of Shezad’s film, which I confusingly have now titled “A Distant Episode,” even though it has nothing to do with “A Distant Episode.” That’s going to show at Projections as well on Friday. The thing was that Shezad’s film was the first thing that I shot, and I shot it really differently in black-and-white Cinemascope. I originally thought the whole thing was going to be in Cinemascope, but decided to shoot in a different format. So technically it didn’t fit as well. In the installation, there’s these spaces that are constructed out of the remnants of old film sets, and from the outside they look like film sets, but on the inside they are more transformed into a cinema space. I would like to show the footage of Mrabet in some other way, because it’s really strong in its simplicity—just Mrabet telling stories to camera, which goes back to this very simple idea of verbal storytelling that’s passed down orally.

I did some second-unit filming for Oliver, as a kind of exchange for being there, so I would do some shots for his film if they were under pressure and needed something down that I could do. There’s one shot they asked me to do of a guy in front of a taxicab, and he’s looking over his shoulder, listening to people in the back, and I think it ended up not being in the film. It’s this sort of fragment of narrative that no longer has a place where it was meant to be. And the installation has a few of these kinds of moments, giving life to things you wouldn’t normally see in a finished film. In one of the spaces there’s all the footage I shot for one scene in the feature. It’s completely unedited: half an hour of footage of the camp scene where they sing the song, so you see repeated shots and repeated lines. It’s another way of showing the construction, but also showing who these people are in a way. You get to see glimpses of who they are within the film but also outside of the film.

I feel like that part of the film is one of the most accurate representations of being on a set—a lot of the tedium and then the little frustrations that no one speaks about because you have to move on to the next thing. When you talked about the installation previously, you had said that Pere Portabella’s Vampire Cuadecuc [71] was a point of inspiration. But I was reminded of another film you had done, Sørdal [08], which is so different from this.

Yes, but that’s definitely a precursor. That idea is much more minimal and modest. I didn’t need a crew for that one. But yeah, it’s these things in the landscape that are both real and fake. That’s very simple, but it’s a kind of beautiful idea: when does the reality end and the fiction begin, or vice versa. It’s always been a kind of blurry boundary. It’s something I am trying to tackle head on with this film.

How would you say your approach was different between this film and Sørdal? Is it just having the means to sort of get really big with it?

Partly. I think when I make Sørdal I wasn’t even intending—well, I didn’t really know exactly what I was looking for. I was up in Norway for a while and that was one of the things that came out of that, I guess. Since then I have had ideas and have wanted to make a film that was showing more directly the construction of a film. And you know, Vampire Cuadecuc was the closest example to what I wanted, because it’s neither. Most of the behind-the-scenes films are either very clearly a documentary or a fiction. You know, like Day for Night, Le Mépris, and State of Things being the fictions, and then the documentaries like Burden of Dreams or Hearts of Darkness. And Vampire Cuadecuc was one of the few where you don’t really know what it is, or what you’re looking at a lot of the time. I kept coming back to this idea of making a film of showing the apparatus but also not. So then it was also a matter of finding filmmakers who would allow me to do that. And Shezad and Oliver were both very generous letting me do that. I’ve used the word parasite, and it does feel like that. You are kind of sucking on their lifeblood, this thing that they’ve spent a long time putting together, these images, these people.

But also it’s there in the world. For Oliver, especially, being a Sufi, he’s says that “none of this is mine.” It’s slightly different for Shezad, because he’s an artist and he’s put these things together very intentionally. I think it becomes a bit more complicated, this idea of who this stuff belongs to. I mean, “belong” is slightly the wrong word. So finding those two was really key, but that happened simultaneously with me thinking about wanting to make a film in Morocco with Mohamed Mrabet and Paul Bowles. These two things were originally going to be completely different, but then these two friends making films in Morocco invited this kind of collision. So that’s what it grew out of.

The original story is very visceral, and it’s almost driven more by smell than it is by imagery or sound. When you were creating images and working to find the right soundtrack for your film, did that visceral sense influence you, or were you making decisions based on your own experiences of the country?

In the end it had to be based more on my own experiences. I wanted to create a similar feeling, and get that sort of sense of dread and uncertainty that’s in the story, but also to get the dirt and the heat and the kind of elemental feel that you get there. In the end, I had to just kind of trust my instincts. I spent a lot of time there. I went back quite a few times and traveled around with Oliver and looked at landscapes. Like always, I try and spend as much time in a place to get a good feeling for it rather than just fly in and fly out. I wanted to capture the thing in the story, which in a way is the thing you can’t quite put your finger on it. It’s the feeling underneath the narrative. It’s hard to explain how I can get images other than they just feel right.

Can we talk about costumes in this? I’m thinking not just of the tin can outfit, but also the man who lures him into the desert who has that amazing pointy hood. Were the costumes designed, or did people just bring their own clothing?

No, they were designed. I had a really good costume designer, Julie Verges. It was quite a lot of back and forth, usually over email. I sent her some drawings. The tin can outfit was very clear in my mind of how it had to look, and then she sent tests back of how she could possibly make it. After a number of tests we found the right way of doing it and then she did a fantastic job. It looks exactly how I imagined it. With the other costumes, she would just put things together and then send me photographs and variations.

In the pre-production in Morocco, we went to studios and chose costumes, guns, and horses. I chose the horses out of about 40 different horses. With the four bandits, the casting person there had sent me a bunch of photographs, and I’d chosen about six or eight to meet. When the day of casting came about, and I was expecting to meet these eight people, a lineup of 30 guys showed up. So I had to walk down and pull out the ones I was interested in. It was really strange, but they’re amazing. All of the guys I saw that day are all stunt men who specialize in horse riding. They all do a lot of films made all over the world, usually period pieces like Bible epics and Ridley Scott movies. So these are the guys that are usually in the background on horses, and it was really nice to be able to bring them to the front and give them lines and more presence on camera.

They’re all really good actors.

Yeah, I was amazed. I think they’re really good. They retain their own self. At the end of every scene, my sound recorder and designer Philippe Ciompi always calls for silence so he can get the room tone or the ambience of a place so that he can use it later. Whenever he cries out for silence, everyone just sort of stops moving and kind of sits around. I continued filming in those parts, and some of those make it into the film. There are bits I really like, because there are people who really inside themselves, just sitting there in silence, not allowed to talk. I’m really happy with those kind of non-moments.