News to Me: The Village Voice Live, Soderbergh, Zhao

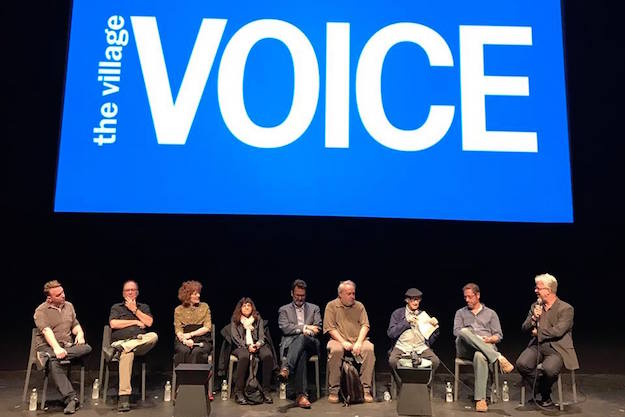

“We’re gonna try and avoid nostalgia tonight,” said David Schwartz, chief curator at the Museum of the Modern Image, inaugurating a panel discussion Tuesday night with former film critics of the Village Voice.

But the nostalgia was palpable at the Museum, as were the passions in the candid, often rueful reminiscence concerning the rise and infuriating destruction of the Village Voice after 60 years. This past August, recent billionaire owner Peter Barbey pulled the plug on what was once a quintessential New York institution, calling the occasion “kind of a sucky day.”

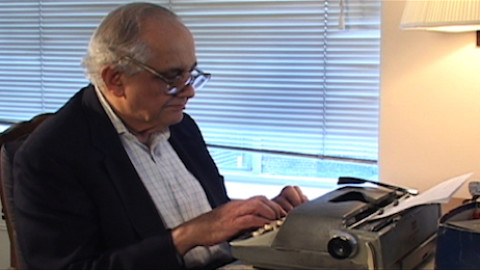

The October 2 panel was a late wake for the Voice by some of its most esteemed film writers: Jonas Mekas—who began its film coverage in the late 1950s and wrote its “Movie Journal” column—Amy Taubin, J. Hoberman, David Edelstein, Michael Atkinson, Nick Pinkerton, Stephanie Zacharek, and Bilge Ebiri. They gathered to remember the newspaper’s legacy in American film criticism and vented their frustrations at the current state of print journalism.

Mekas set the scene for the panel by reading aloud a list of the movie theaters in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s. From his “Oh! Team CCCB” totebag, he pulled out a small camcorder and recorded a video of his litany (“Not a film,” he insisted). For current Hollywood offerings, “there were 15 moviehouses on 42nd Street! You could sit all night there for nothing, and nobody would throw you out.” Those interested in classical Hollywood films and the European avant-garde went to MoMA. The emerging avant-garde was at Cinema 16; politically leftist films were at the Film Club on 6th Avenue and 11th Street; films on dance debuted at Livingston on 50th Street; and so on.

Mekas’s opening captured the wistfully proud tone for the rest of the evening—a cross-generational toss-around of Voice memories. Taubin underlined the role of the publication’s editors, who were rarely mentioned in eulogies to the Voice but who “made the writers what they could be.” J. Hoberman said that Richard Goldstein had “the best journalistic instincts of anybody I ever met”; Taubin singled out Lisa Kennedy for encouraging her and The New York Times‘ Manohla Dargis, another Voice alum, to develop their ideas.

Bold opinions were the norm at the Voice in its heyday. Hoberman recalled when Andrew Sarris declared Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho as the true site of the most exciting avant-garde in American film, and marveled over Molly Haskell as the first major film critic to openly declare herself a feminist. He underlined the Voice’s singular identity, intensely local and fiercely oppositional.

“You were really encouraged to be a personal journalist,” said Hoberman. “Jonas and Jill Johnston were bloggers decades before this ever existed. People wrote about their sex-lives, their break-ups, all kinds of things in the first person.”

The Voice critics ultimately shifted their attentions to the potential in the burgeoning new phase in repertory film culture. Audio of the talk is available below.

Films on the Horizon

Ken Loach has begun shooting Sorry We Missed You in Newcastle, England. The follow-up to his Palme d’Or winner I, Daniel Blake (2016) tracks a family who struggles to remain afloat in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis . . . Bertrand Bonello (Nocturama) will make Zombi Child, his seventh feature film, with Arte France Cinéma. Set in 1962 Haiti and modern-day Paris, it will focus on the destiny of a Haitian girl, the victim of a voodoo spell that has turned her into a zombie . . . And just in case you missed it betwixt festivals, Chloe Zhao (The Rider) will direct The Eternals for Marvel. … Netflix has bought the global rights to distribute Steven Soderbergh’s basketball film High Flying Bird, from a screenplay by Tarell Alvin McCraney. Like Unsane, Soderbergh’s previous film, it was shot entirely on iPhones.

Readings

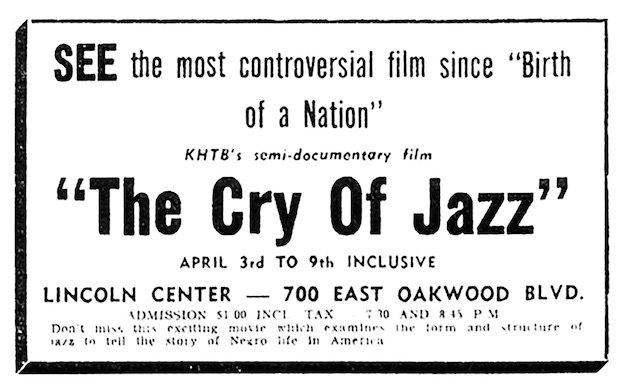

✸ Last week, the Library of Congress added hundreds of hours of footage to their newly launched National Screening Room. Highlights include the 1959 documentary short The Cry of Jazz; Oscar Micheaux’s Within Our Gates (1919); an interview with Twilight Zone creator and screenwriter Rod Serling; and 33 newsreels from All-American News, a news series aimed at black audiences in the 1940s and 1950s.

✸ “On the other hand, where does that leave someone who dislikes it?” Wesley Morris writes about the role of “moral correctness” versus “quality” in evaluating culture, in The New York Times Magazine.

✸ Le CiNéMa Club’s Film of the Week is Aware, Anywhere, the 2017 documentary on Olivier Assayas, whose latest film is Non-Fiction. As part of the series Cinéma de notre temps, director Benoît Bourreau follows Assayas on the road as he directs and promote Personal Shopper. He discusses his 30 years of filmmaking and his process with frequent Assayas collaborator and actor Kristen Stewart.

✸ Scholar James Naremore has launched his own website. As Naremore writes, “this is a place where I can publish essays or lecture that haven’t appeared elsewhere, plus old journal articles, film reviews, and out-of-print books.” Pieces now up on the site include a dissection of Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet (1948), which was omitted from his now-classic 1988 study of film performance, Acting in the Cinema; an up-to-date primer on Orson Welles; an article for Sabzian on Vincente Minnelli’s aesthetics; and many interviews.