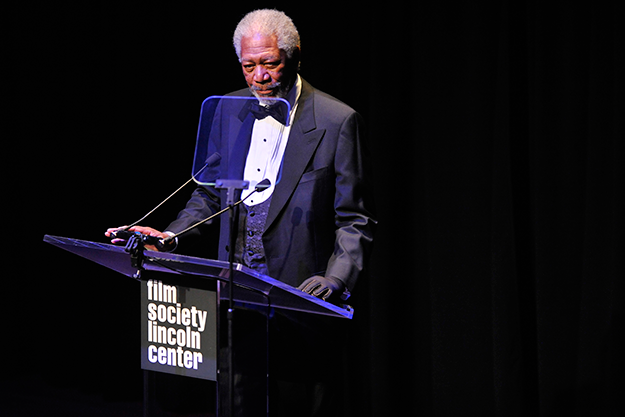

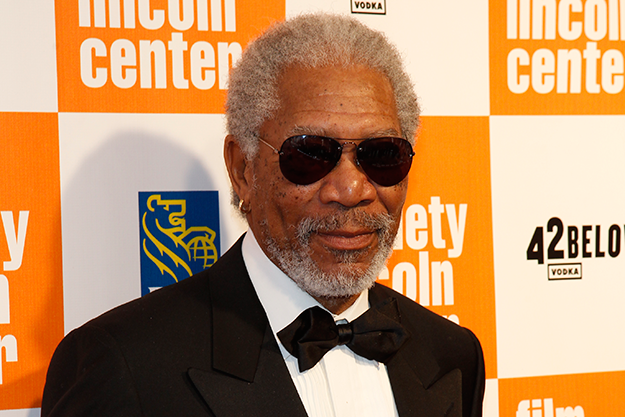

Voice of Reason: Morgan Freeman

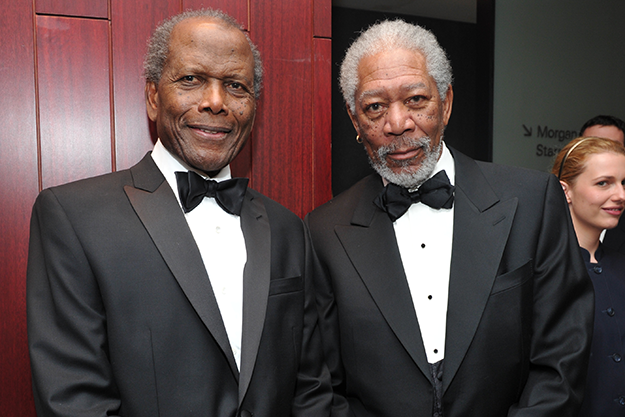

Imagine that an alternative Supreme Court is to comprise not venerable legal minds but actors chosen for their shrewdness, aura of authority, and ability to assure the American people that the rules of the Constitution are being upheld. For the eight Associate Justices, we probably couldn’t improve upon Angela Bassett, Anna Deavere Smith, Tom Hanks, Tommy Lee Jones, Robert Redford, David Strathairn, Meryl Streep, and Oprah Winfrey. Because James Earl Jones and Sidney Poitier would likely rule themselves out on age grounds, there is clearly only one conceivable choice for Chief Justice: Morgan Freeman. The soothing baritone of the preeminent movie narrator of modern times would alone militate for live broadcasts and webcasts of the court’s oral arguments.

What a boon it would be to know that Freeman was bringing wisdom, gravitas, and immeasurable calm to the highest bench in the land. The idea isn’t original: as well as playing Chief Justice Frawley in a 2015 episode of Madam Secretary, Freeman was an unwaveringly presidential president in Deep Impact (1998) and a steely acting president in both Olympus Has Fallen (2013) and London Has Fallen (2016). He was also the judge in The Bonfire of the Vanities (1990) and twinkly-eyed omniscience personified as the white-clad God in Bruce Almighty (2003) and Evan Almighty (2007). Freeman’s most indelible leader, though, is his Nelson Mandela in Clint Eastwood’s post-Apartheid reconciliation drama Invictus (2009), a project Freeman initiated. It is a kind of companion piece to Bopha! (1993)—the only film Freeman has directed—which is a trenchant adaptation of Percy Mtwa’s stage tragedy about a proud black police sergeant (Danny Glover) too blinkered to see that he is an efficient tool of apartheid at a time when Mandela is still in prison.

Freeman’s Mandela delivers his moral justification for sanctioning the South African national rugby team traditionally beloved of the white minority and hated by the blacks after his skeptical chief of staff (Adjoa Andoh), seated to his right in the back of his car, suggests “this rugby is just a political calculation”: “Uhr,” he begins, before clearing his throat, “it is a human calculation. If we take away what they cherish, the Springboks, their national anthem, we just reinforce the cycle of fear between us. I will do what I must to stop that cycle, or it will destroy us.” Spoken by an actor less canny, screenwriter Anthony Peckham’s words might have sounded platitudinous, but—amplified into a terse declaration of intent by Eastwood via two angles on Freeman that accentuate the obdurate set of Mandela’s jaw and two cuts to his raptly listening driver that make an audience of him—they achieve through his measured diction an uncontestable resolve. Freeman’s throat clearance and pauses are integral to Mandela’s expression of his conviction.

This is not to say that Freeman’s men of integrity are monolithic to the point of Lincolnian. He opens cracks of fallibility, vulnerability, or wrong-headedness in his dignitaries and officials, as he does in the socially unrecognized men he plays. He did not portray Mandela as “a saint… but a man with a man’s problems,” as one of his bodyguards (Patrick Mofokeng) says of him; he also made him sly, manipulative, and drily humorous. Sometimes those cracks are hairline in breadth, on other occasions gaping. In John G. Avildsen’s Lean on Me (1989), he appears as the real-life principal Joe Clark who, appointed to prevent Paterson’s riotous Eastside High School from falling under New Jersey state control, purges it of hooligans and drug dealers, and strives to improve the failing student body’s minimum basic test scores. Michael Schiffer’s script quickly propels Freeman’s megaphone-wielding Clark into his tyrannical phase—an evolutionary episode for most movie protagonists that usually occurs later in the story. Unlike Louis Gossett Jr.’s drill sergeant in An Officer and a Gentleman or J.K. Simmons’s jazz instructor in Whiplash, say, Clark is less a martinet than a rash disciplinarian. Compassionate at core, he takes a “tough love” approach to one drug-abusing student (Jermaine Hopkins) and sensitively intervenes to reconcile another (Karen Malina White) with her troubled mother, but he hectors his staff unremittingly. Only after he is rebuked as “an egomaniacal windbag … thoughtless and cruel” by his steadfast deputy (Beverly Todd) does he temper his belligerence, responding then with a rousing us-against-them speech on test day. He too has had to learn. Beyond some late benign smiles, however, Freeman refuses to sentimentalize Clark or ingratiate him with the viewer, which is why he is so memorable in the role.

Lean on Me was released in Freeman’s 52nd year, during which he also appeared in Walter Hill’s Johnny Handsome, Edward Zwick’s Glory, and, most notably, Bruce Beresford’s Driving Miss Daisy, which conferred on him the stardom augured by his electrifying turn as the pimp Fast Black in Jerry Schatzberg’s Street Smart (1987). He had served a protracted apprenticeship and was 34 when he made his first credited film appearance, as “Afro,” in 1971’s Who Says I Can’t Ride a Rainbow!, a fact his movie-star character pointedly alludes to in 10 Items or Less (2006). Like Gene Hackman and Robert Duvall, 34 and 31 respectively when they made their big-screen debuts, Freeman brought to his movie career the demeanor of a man hardened or—in the case of his deranged Arkansas prison inmate in Brubaker (1980)—ravaged by experience. Sometimes ruefully transmitted by him as the knowledge that life is an ordeal to be endured, this seasoning is germane to his mature persona, and especially his formidable performances in Driving Miss Daisy, Glory, Eastwood’s Unforgiven (1992) and Million Dollar Baby (2004), Frank Darabont’s The Shawshank Redemption (1994), David Fincher’s Se7en (1995), Steven Spielberg’s Amistad (1997), and Ben Affleck’s Gone Baby Gone (2007).

Born in Memphis in 1937, Freeman was the fourth eldest child of a family of five boys and a girl born to a teacher and her barber-bootlegger husband. The siblings were mostly raised in Mississippi by their grandparents but spent their summers in Chicago, where their parents had found higher-paying jobs. Freeman was cast as Little Boy Blue in a school play when he was 8 or 9; at 12 he won a state prize for his acting in a school pageant. When he was 18, he turned down a partial drama scholarship from Jackson State University to enlist in the Air Force. As a radar mechanic, he served a year and a half and was close to being accepted for pilot training when he realized, from looking at the dashboard in a jet airplane’s cockpit, that his notion of flying and fighting was a fantasy inspired by war films. Another cockpit—the stage—beckoned him.

In 1961, he moved to California and worked as a transcript clerk at Los Angeles City College. He didn’t always eat, but he took acting lessons at The Pasadena Playhouse and trained as a dancer in San Francisco, which, he has said, gave him “carriage.” (As graceful as a big cat, like John Wayne, Freeman saunters in Street Smart, leaving the “pimp roll” to Erik King, who played Fast Black’s protégé; restlessly prowls the school corridors in Lean on Me; and bestrides the English greensward in 1991’s Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves.) He danced professionally at the 1964 World’s Fair. Touring as a chorus member and understudy in Peter Shaffer’s The Royal Hunt of the Sun in 1966, he came on in the speaking part of an Inca general in a Des Moines performance. “The feeling of rightness and power that washed over me on the stage that night came as a revelation to me,” he recalled when I talked to him for Interview magazine in 1996. “I said, ‘This is what you do, this is where you really shine. The following year, I got my first job Off-Broadway in a play called The Niggerlovers [by George Tabori].” Also in 1967, he appeared alongside Pearl Bailey and Cab Calloway in an African-American Hello, Dolly! on Broadway. From 1971 through 1977, he was Easy Reader, Count Dracula, DJ Mel Mounds, and other characters on PBS’s popular remedial-reading show The Electric Company. It was steady but grueling work and he drank to get through it. If the early and mid-1980s were lean years for Freeman as a film actor, he won a joint Obie for his Coriolanus and his Chaplain in Brecht’s Mother Courage and Her Children in 1980 and another for his Messenger in Lee Breuer’s musical version of The Gospel at Colonus in 1984. Less rewarding personally was his stint as a dignified architect in the daytime soap Another World, though it kept the wolves from the door.

Street Smart liberated Freeman as an actor and earned him a first Oscar nomination. Christopher Reeve was the movie’s lead—Freeman its vortex. Schatzberg’s drama tracks the hubris of Reeve’s bland yuppie reporter, Jonathan Fisher, who, like Dr. Frankenstein, creates a monster he cannot control. Given a few days to write a profile of a pimp he has proposed to his Manhattan magazine editor, Fisher fails to find one to fit the bill so he invents “Tyrone,” passes him off as real, and is acclaimed for the story. The DA prosecuting Fast Black for killing a john assumes he is Tyrone and pressures Fisher to turn over his nonexistent notes, even as Fast Black persuades Fisher to fake an alibi for him. Freeman had been advised by his agent not to return to Hollywood to take advantage of the Blaxploitation boom. It was good advice. Sleek though he is, Fast Black is a character unhindered by Blaxploitation mannerisms. Capable of charming men and women at will, he is also a narcissist with a hair-trigger temper. His menacing of a kid who tussles with him during a casual basketball game and the prostitute Punchy (Kathy Baker), whose breasts he has imprinted with cigarette burns, denotes he is a psychopath of the order of Robert Mitchum’s Max Cady in Cape Fear. His performance prompted The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael to ask rhetorically in her review: “Is Morgan Freeman the greatest actor in America today?”

Espousing Fast Black’s volatility may or may not have exorcized something in Freeman: his voice dropped a few octaves and the sage in him emerged. He won a third Obie for originating the tactful, patient, and quietly droll chauffeur Hoke Colburn of the eponymous Southern Jewish septuagenarian in Alfred Uhry’s Driving Miss Daisy. Prior to directing the film, Beresford had worried that Freeman was too young to play Hoke, who ages from 50 to 85, but he must have perceived early on that the actor has a genius for transcending the limits of age, race, class, and period to emphasize the nodal points of conflict in drama: though Freeman’s 19th-century characters in Glory, Unforgiven, and Amistad are tintypes made flesh, they boldly and unironically manifest contemporary progressive attitudes about honor, duty, loyalty, and equality. It became fashionable after Driving Miss Daisy won the Best Picture Oscar to knock it as nostalgia for the segregated South of the pre–Civil Rights era, but that kind of presentism makes general what is specific in Hoke and Daisy’s friendship: the hewn-out kindness and trust shown by one outsider to another. In its genteel way, it anticipated the naturally undemonstrative friendships between Eastwood and Freeman’s retired outlaws in Unforgiven, between Tim Robbins and Freeman’s prison “lifers” in The Shawshank Redemption, and between Brad Pitt’s rookie homicide detective and Freeman’s jaded veteran in Se7en—his performance in that dank neonoir a masterclass in world-weariness and stoically staved-off dread. And, of course, between Eastwood’s cantankerous trainer and Freeman’s kindly, partially sightless ex-fighter—a role that won him the Best Supporting Actor Oscar. Working with Freeman in Unforgiven, Eastwood found a partner his equal in strength and ribaldry: “Do you use your hand?” Freeman’s Ned Logan inquires of Eastwood’s widowed William Munny; it’s to avenge Logan’s murder that Munny regretfully turns killer again, leading to the film’s bloody Götterdämmerung. In Million Dollar Baby, the two men express their love for each other by bickering relentlessly, as old marrieds often do.

Irreverence is not the least of Freeman’s attributes because—like his seldom-mentioned toughness—it helps preserve him from the kind of saintly reputation with which no serious actor wants to be burdened. This is why the aforementioned 10 Items or Less, a delightfully nonchalant indie written and directed by Brad Silberling and executive-produced by Freeman, is such a revelation. The movie star Freeman plays has been too long off the screen, but his jocularity conceals any anxiety he has about committing to a no-budget project exactly like 10 Items or Less. Researching the role of a supermarket manager in featureless Carson, CA, “Him” (Freeman) contrives to have an exasperated Spanish cashier, Scarlet (Paz Vega), give him a lift home. They drive around, he coaches her how to succeed in a job interview, he learns something in return—that’s all. References to Ashley Judd (Freeman’s five-time co-star) and Eastwood indicate that Him is at least a semi-autobiographical version of Freeman. If he is, indeed, gregarious, flirtatious, charming, and loosey-goosey (actually impractical), and a bit of a loner in his downtime, we should marvel all the more at his evocations of dignity, gravity, nobility, and, in a rare case like Street Smart, instability and wickedness.

“He moves people for the better; that is his calling in life. Some call it the Madiba magic. I’m not sure that magic can be explained,” Freeman said of Mandela. It doesn’t trivialize the suffering and invincibility of the South African liberator to ponder Freeman’s immense capacity to move people or his “magic,” which are unique in their own way—and no less mysterious.

The 43rd Chaplin Award Gala takes place on Monday, April 25.