Married to Cinema: The Films of Kinuyo Tanaka

This article appeared in the March 17, 2022 edition of The Film Comment Letter, our free weekly newsletter featuring original film criticism and writing. Sign up for the Letter here.

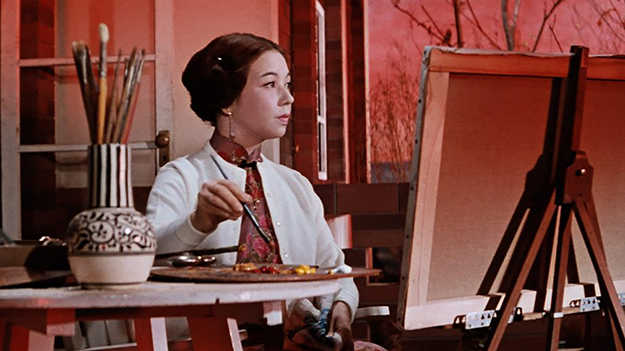

The Wandering Princess (Kinuyo Tanaka, 1960)

Kinuyo Tanaka was 14 when she first stepped in front of a movie camera, and during the next half-century she appeared in more than 250 films and directed six. Explaining why she never became a wife or a mother, she liked to say that she “chose to marry cinema.” When she moved behind the camera, she looked at women’s lives with realism and ardor for the ways they find to assert themselves within stifling circumstances.

Perhaps because she lived so much of her life in the movies, she was drawn, as a director, to the innately cinematic effects of everyday spaces and actions. She liked to place her camera outside the threshold of a room, so that the sliding shoji screens of Japanese homes functioned like wipes, gracefully revealing or concealing the scene within. In Tanaka’s best film, Forever a Woman (1955), the constant opening and closing of doors becomes an unforced expression of the possibilities that emerge or vanish for the heroine as she moves from a disappointing marriage through an unrealized romance, recognition as a poet, and a desperate struggle with breast cancer. Even as she stubbornly resists being framed by society in a conventional narrative of gallant sacrifice, she is visually imprisoned by windows; the film’s final image is a barred gate sliding shut on a hospital ward.

In Love Letter (1953), the first film Tanaka directed, a momentous reunion of long-separated lovers occurs amid the swarming crowds at a railway station; just as the man and woman come face-to-face, the camera retreats into a train car and the door slides shut, trapping them for a moment in the window. Then the train glides away, carrying us into an idyllic flashback of their childhood together. A film about survivors mired in postwar disillusionment, Love Letter approaches with clear-eyed compassion the touchy subjects of Japanese men’s humiliation in the face of defeat and occupation, and the shame directed at women who slept with the conquerors. Three years after Tanaka was shattered by the hostile reaction of the Japanese press to her goodwill tour of the United States, she portrays a country scrambling for American magazines, fashions, and dollars, while nursing a sense of loss and wounded pride.

Tanaka has long been cited as a pioneering female filmmaker in Japan, but it is only in the last few years that her films began to receive international screenings and attention. Now, Film at Lincoln Center and Janus Films are presenting all six titles in lustrously restored prints (accompanied by a sampling of her on-screen performances). They range from gentle romantic comedies (The Moon Has Risen) to three-hankie tragedies (Forever a Woman), from realist studies of postwar social problems (Love Letter, Girls of Night) to ceremonious feudal-era costume dramas (Love Under the Crucifix).

The films she directed have some of the same qualities that Tanaka brought to the screen as an actor: natural warmth, emotional honesty, and an ability to devastate with the simplest means—like the way her brightly appeasing smile occasionally collapses to reveal the dispiriting effort behind it. At Shochiku, the oldest of Japan’s four major film studios, she was a fixture in romantic melodramas of the 1920s and ’30s, becoming so beloved that her name was sometimes used in film titles (Kinuyo’s First Love, Kinuyo the Lady Doctor). While she remains best known in the West for her 15-film partnership with Kenji Mizoguchi, for whom she plumbed harrowing depths of suffering and degradation (Women of the Night, The Life of Oharu, Sansho the Bailiff), she had prolific and long-running collaborations with other directors, including Yasujiro Ozu, Keisuke Kinoshita, and Hiroshi Shimizu. By the early 1950s she had reached a turning point: she was in her forties, and, seeing herself aging out of the leading roles she had so far played, she was eager to try her hand at directing, at a time when there wasn’t a single female director in the Japanese film industry. Some of the prominent filmmakers she’d worked with supported her: Kinoshita and Ozu gave her scripts (for Love Letter and The Moon Has Risen, respectively), and Mikio Naruse made her his assistant for a time in 1953. Mizoguchi, by contrast, vocally opposed the move by his “muse” to take the helm herself, a disappointing response from the man whose films chronicled the brutal repression of Japanese women.

Though her career as a director lasted only a decade, Tanaka worked at major studios with substantial budgets and big stars like Machiko Kyô, Masayuki Mori, and Tatsuya Nakadai. Her second film, The Moon Has Risen (1955), features Ozu regular Chishû Ryû as (what else?) a widowed father of marriageable daughters. But the movie belongs to Mie Kitahara as the spunky young Setsuko, whose clumsy efforts to set up her shy older sister with an equally timid suitor provoke the funniest scenes. At one point, she solemnly directs the willing-but-clueless family maid, played by Tanaka herself, in how to impersonate her sister on the phone. Against the gorgeous backdrop of Nara’s ancient temples and moon-silvered parks, the minutiae of polite conversations, shot through with oblique hints of hidden feelings, take on dramatic weight. As in the work of Jane Austen, trivial follies give rise to blinding flashes of self-knowledge.

On the much larger canvases of The Wandering Princess (1960) and Love Under the Crucifix (1962), history unfurls through women’s eyes. Filmed in widescreen and richly saturated color, both have a tableau-like formality that evokes the stultifying ritualism of the ruling classes and the rigid rules that govern the way women dress and move, giving them scant control over their bodies or their fates. In The Wandering Princess, Kyô plays an aristocratic woman married off to the brother of the Manchurian Emperor, an alliance intended to cement the “friendship” between Japan and Manchuria—a euphemism for the latter’s status as a Japanese colony and puppet state. With the outbreak of World War II, she is plunged into a harrowing ordeal as a refugee and then a prisoner of the Chinese People’s Liberation Army. Impressive in its sweep and humane vision, the film’s main flaw is its flawless heroine—although her dutiful, self-sacrificing endurance cannot save her sister-in-law, a woman psychologically broken and discarded by the machinery of power.

Love Under the Crucifix, Tanaka’s last film as a director, is a lush tale of doomed lovers set against the backdrop of warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign to stamp out Christianity in the late 16th century. Although it opens with images of a flaming battlefield, this jidai-geki (period film) eschews armed combat to focus on quieter but no less fierce conflicts: between austere religious devotion and earthly passion; between ostentatious, abusive power and the humility and integrity expressed by the tea ceremony. Ogin (Ineko Arima, a founder of the company that produced the film), the stepdaughter of the legendary tea master Sen no Rikyû (Ganjirô Nakamura), boldly declares her love for the pious, and married, Christian samurai Ukon (Nakadai), saying that she would accept eternal damnation just to have him once. As in the rest of her work, Tanaka’s treatment of female desire—and female solidarity—is remarkably frank and sympathetic here. Early in the film, Ogin witnesses a gruesome procession taking a woman (Keiko Kishi) to be crucified for refusing to comply with a warlord’s customary right of droit du seigneur. She gazes at the defiant captive with more awe than pity, observing, “She looks so alive!”

Forever a Woman (also known as The Eternal Breasts) doesn’t flinch from the unruly, confused response of Fumiko (Yumeji Tsukioka) to her illness and her changed body. After a double mastectomy, she cycles through anger, grief, spurts of gaiety, flirtatiousness, tortured vanity, and interludes of serenity. In one scene, she luxuriates in the bath at a friend’s house, and when the other woman is horrified by an accidental glimpse of her scars, Fumiko urges her to look at them again, then blurts out that she was in love with the friend’s now-deceased husband. Near the end, dying in a hospital, Fumiko asks her mother to wash her hair, and on a hot night she lies down next to Ôtsuki (Ryôji Hayama), a visiting reporter with whom she has formed a bond, reaches out to caress him, and begs him to make love to her. Graced with small moments of ordinary kindness, the story refuses to locate meaning in the senselessness of disease, and it builds to an ending that quietly, mercilessly pulverizes your heart.

In its sensitive and complicated account of what it means to be an artist, a woman, a mother, and a physical being facing mortality, Forever a Woman sums up the unsentimental humanism of Tanaka’s vision. Though she directed her last film in 1962, she continued acting until a year before her death in 1977. Few unions have been more passionate or fruitful than her marriage to cinema.

Imogen Sara Smith is the author of In Lonely Places: Film Noir Beyond the City and Buster Keaton: The Persistence of Comedy. She has written for The Criterion Collection and elsewhere, and wrote the Phantom Light column for Film Comment.