All Hail King of Jazz!

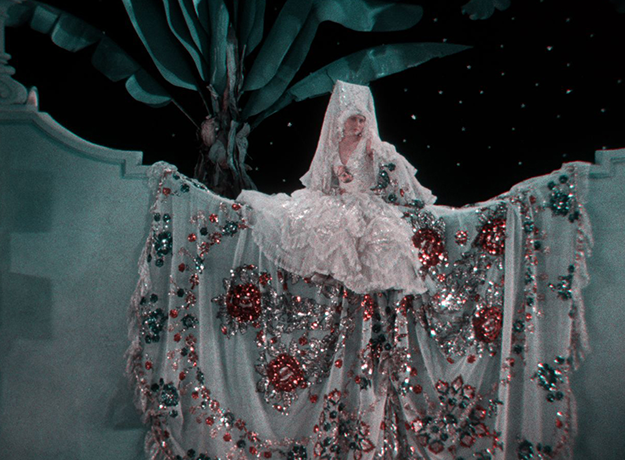

Two-strip Technicolor takes some getting used to. The forerunner of the beloved three-strip process used for much of the classic-film era, two-strip renders white actors’ complexions in rosy shades of pink and does a great job with greens and reds. But most yellows are impossible, and true-blue is basically out of the question. The overall effect is somewhat abstract, but when restored to its original luster, also very beautiful.

Last year, James Layton and David Pierce’s weighty history book Dawn of Technicolor, 1915-1935, helped revive interest in early Technicolor; this year, they are back with King of Jazz: Paul Whiteman’s Technicolor Revue. Usually it is only the warhorses, the Gone With the Winds and the Casablancas of this world, that get a soup-to-nuts production history like this one. Universal Pictures’ 1930 film King of Jazz has had a cult following for many years, and that cult is the reason it was saved, as Layton and Pierce prove in great detail. But many others—including me, I confess—had barely heard of the movie.

No film shows off early Technicolor better, as audiences have been finding out this year. Directed by innovative Broadway veteran John Murray Anderson (his sole film as director) and made to promote the talents of bandleader Paul Whiteman, the king of the title, it’s a revue of stunning lavishness and quite a bit of historical importance. (It was, for one thing, the film debut of a crooner name Bing Crosby.)

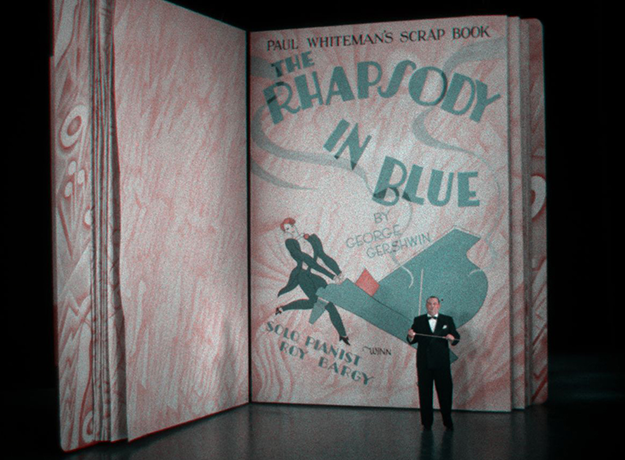

It’s a resurrection that has been a long time coming. King of Jazz fizzled at the box office, had a re-release in a drastically shortened form, then spent more than 30 years out of sight and eventually had to be reassembled, like a dinosaur skeleton, using bits and pieces from multiple sources. I saw it this spring with a capacity crowd at the Museum of Modern Art during the “Junior Laemmle” series, and it’s safe to say that King of Jazz finally got the rapturous reception it was denied for more than 80 years. The MoMA audience (not exactly pushovers) burst into applause for the biggest numbers, such as “Rhapsody in Blue,” in which Whiteman’s orchestra appears in a gigantic piano and silver-and-choral clad chorus girls dance in perfect synchronization. There was no blue to be seen—the early Technicolor rendered it all in teal—but it was splendid, all the same. Other showstoppers included “It Happened in Monterey,” a romantic Mexican number with John Boles and the Russell Markert Dancers (who later became Radio City’s Rockettes); “My Wedding Veil” (far from the most mobile number, but a treat for any student of fashion history); and a delightful, visually sophisticated scene of a giant Whiteman watching a miniature version of his orchestra emerge from a suitcase.

Layton and Pierce start with a primer on Whiteman, the most popular bandleader of the 1920s. Despite his “King of Jazz” sobriquet, Whiteman was not always all that jazzy; he limited improvisation and arranged his numbers in the symphonic style he preferred. “I could never understand why jazz had to be a haphazard thing,” he said. (Whiteman’s cornetist for a time was the great Bix Beiderbecke, but alas, he had departed before the movie was made.) Whiteman played large-scale, easily danceable music that was perfect for the “revue” craze that swept Hollywood in the early talkie era.

Or so it seemed to Universal, which signed Whiteman to a contract in 1928 and put director Wesley Ruggles in charge of draping a movie around the portly star. Whiteman disliked the first script—it was a considerably fictionalized biopic, and the basic problem was, Whiteman didn’t want to act. During the ensuing arguments, Ruggles jumped ship for RKO where, Layton and Pierce write, his film “was shot, cut, and released before any cameras would roll on King of Jazz.” Next up was Paul Fejos, the “Magyar Genius” who had just shot Broadway, put in charge by newly anointed production head Carl Laemmle Jr. Unfortunately Fejos also didn’t have much affinity for the project, although at least he agreed a love story wasn’t the way to go. “But what on earth will you do with him?” Fejos asked about Whiteman. “He’s a man inordinately fat.”

Time ticked on and costs mounted, even after Anderson was brought on to create a revue like the ones that made his theatrical name, Universal having given up on making an actor out of Whiteman. The final film plays like an impossibly huge stage production, complete with humorous “blackout” skits between the production numbers.

The book gives background and brief bios on every performer. Many came from the stage and did numbers that they had honed for years, such as Marion Stadler and Don Rose, who do a rag-doll number that finds Stadler being pushed, pulled, and otherwise contorted into a number of jaw-droppingly flexible positions. “Some scenes may not work as well as others,” admit Layton and Pierce, “but King of Jazz is the sum of all of its parts. The spectacle and the quality of the staging are the star.”

The film comes with some caveats, as Layton and Pierce freely admit. The most obvious problem is that for any modern audience, a film with the word “jazz” in its title simply has no business being this white. The big finale proposes that the music came from the great American melting pot. And thus a succession of Germans in lederhosen, Scots in kilts, Volga boatmen, and various other European nationalities in matching parade costumes come on screen to perform an ethnic number of some sort, after which each group descends into a literal, gigantic, gold-painted pot. Eye-popping spectacle though this is, it is also a dismaying view of jazz, as is the introduction to “Rhapsody in Blue,” when the superb dancer Jacques Cartier does a “primitive” number in head-to-toe black body paint. The authors do a good job of putting this stuff in historical context; they neither condescend nor excuse.

The production delays that Layton and Pierce describe cost the movie more dearly than anyone could have foreseen. By the time King of Jazz made its bow, Hollywood had indulged its eternal tendency to run a trend into the ground, and revues were such a drag on the market that some other musicals were being advertised with taglines like “Positively not a revue!” There was also the little matter of what happened on Wall Street in October 1929. The worst of the Great Depression was in the future, but the effects of the crash were already being felt. Reviews were mostly dismissive, although the frequently dunderheaded Mordaunt Hall of the New York Times liked it, and art director Herman Rosse wound up winning an Oscar for his work. But the wide audience the big budget anticipated simply wasn’t there. Universal didn’t release another musical until the exotically titled Moonlight and Pretzels in 1933.

The revue format did allow Universal to recut the film for foreign markets, splicing in the likes of Bela Lugosi, Swedish-born star Nils Asther, and character actor Tetsu Komai to introduce the numbers for various countries, a process that gets an entire chapter. The movie was surprisingly successful abroad, helping to salvage some of its staggering $2 million cost. In 1933, as Universal’s finances remained precarious, King of Jazz was recut for the American market and re-released, and while it once again failed to set the box office on fire, this time it did turn a profit.

And for many years, that was that. In 1971, Paul Whiteman’s widow, Margaret Livingstone, asked Universal about the status of King of Jazz, and was told they had neither a print nor a printable negative—since the two-color process was obsolete, the fact that they still had the negative didn’t matter. “The eventual rediscovery of the film in the 1960s and 1970s was due to the dedication of archives and individuals,” write the authors, “not the studio itself.” They trace various bits and prints of King of Jazz across Europe and through the holdings of several eccentric collectors, including the legendary Raymond Rohauer. (One of the most important prints, which turned up in the holdings of British late-night film host and historian Philip Jenkinson, may have belonged to Mussolini.) A VHS version was released in the 1980s, but it was missing several sequences, and the degraded color was sad to see.

A movement to name King of Jazz to the National Film Registry, spearheaded by writer and film historian David Stenn and Ron Hutchinson of the Vitaphone Project, finally did the trick. The film’s addition to the registry in 2013 helped justify the expense of a restoration by NBCUniversal, which has over the past few years been paying more attention to its back catalog. And so Layton and Pierce’s book, a micro-history of so many things—popular American jazz, the influence of vaudeville on film, the last years of Laemmle-controlled Universal—ends with a rare look at the magnificent obsessives who often wind up saving films.

Farran Smith Nehme writes about classic film on her blog, Self-Styled Siren, and recently published her first novel, Missing Reels. She is a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.