Interview: Serge Bozon

Always fascinated by the more esoteric corners of genre cinema, critic-turned-filmmaker Serge Bozon has recently taken to the tricky world of comedy. Following the absurdist slapstick riff Tip Top (2013), Bozon has reimagined Robert Louis Stevenson’s gothic parable Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with the help of his longtime screenwriter, Axelle Ropert, who also wrote Bozon’s offbeat musicals La France (2007) and Mods (2002), in addition to directing her own films.

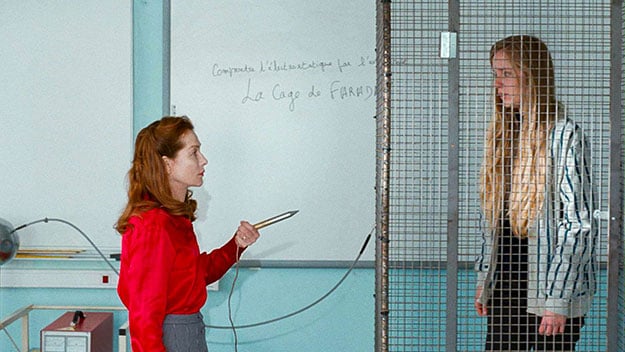

Starring Tip Top’s Isabelle Huppert (winner of the prize for Best Actress at Locarno) as Mrs. Géquil, a long-suffering physics teacher at a technical school for underserved high schoolers, most of them immigrants, Madame Hyde examines urgent social issues through a dual prism of literature and levity. Fed up with her inattentive students and increasingly indifferent to her lovably dopey “househusband” (Jose Garcia), Mrs. Géquil’s frustrations are temporarily eased by the arrival of Malik (Adda Senani), a handicapped student whose inquisitive nature she sees potential in. But when Mrs. Géquil is electrocuted, her daytime struggles become the fuel for a series of nocturnal flights of fiery comeuppance that playfully merge the fatalistic with the fantastic.

Bozon sat down with Film Comment shortly after the premiere of Madame Hyde at the 70th Locarno Festival to discuss his particular approach to comedy, the genre’s capacity for confronting topical subject matter, and the evolution of a filmmaking sensibility that is in increasingly short supply in both America and abroad.

I’m curious about the inception of the project. Was it always conceived as a riff on Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde with a female protagonist, or did that come forward in the process?

It was an idea of Axelle Ropert’s, the screenwriter who I’ve been working with since I started making films. And she had all the details there from the start: a contemporary Dr. Jekyll tale, but with a female in the lead role, who’s also a teacher in the suburbs. It was all planned from the beginning

Do you have any special connection or personal history with the Stevenson story, whether in literature or film?

I was a teacher myself more than 20 years ago in the Paris suburbs—that’s the relation I guess. [Laughs]

Tell me about your ongoing collaboration with Axelle Ropert? Madame Hyde seems to carry a bit of the convivial sensibility seen in some of her comedies, like The Apple of My Eye.

Ah yes, perhaps. It’s hard for me to speak for her, but she has written all my scripts. In the beginning I didn’t write anything—not a single word. But since my previous movie, Tip Top, I have been writing and contributing quite a lot. So we’ve been writing together, but I don’t have much to say about our methodology since it’s a case by case thing, trial and error, a kind of ongoing daily process. Maybe here it does come across, as you say, as a kind of feminine conviviality—a kind of tender touch. At least I hope it does, because there’s an emotion here that wasn’t present in my previous movies. To break it down very simply: I hope the audience will cry at the end. And I would never expect anyone to cry at the end of Tip Top. Or La France, which I thought was moving—I would never expect someone to cry. Perhaps I’m wrong or pretentious for wanting this, but people have told me that they’ve been deeply moved at the end when Isabelle Huppert is destroyed from the inside but still tries to carry on the flame of teaching.

For me, all the scenes at the end of the film are tragic. I don’t think you’d expect, based on the early scenes, which have many light and comical touches, that the film will be so dark or despairing. And I think that comes from the teaching aspects of the story. You have to show what it is to teach, especially for Isabelle’s character who finally manages to do it successfully after 35 years of failure. A kind of seriousness arises from the teaching scenes in the middle of the movie, and gradually something more abstract and more somber comes forward. Perhaps that is a result of Axelle.

You’ve long been interested in genre, but lately you seem particularly fascinated with comedy. Do you find something lacking in modern comedies?

It’s not because I think other comedies are bad, or not as good as mine. I don’t make movies to confront other movies. In the past I confronted them as a writer, through criticism. But not, I hope, as a director. I like a movie to be lively. And where does this lively quality come from? From surprises. There are some directors you can tell from watching their movies what the tone of all the scenes will be, and that’s not lively. The things that make a movie lively is the contrast, the contrast of tones. And there is no better contrast than the one between laughing and crying. So I think for me it’s the pleasure of being surprised and excited. To give a specific example: Howard Hawks, Only Angels Have Wings. What makes this movie so lively is precisely because you move from the laughs to the tears and back again. You cannot anticipate where it will go next. One doesn’t destroy the other. I think they can compete—sometimes a little brutally, but the contrast should exist and not be destroyed in the process.

What I don’t like in French cinema is the distinction between art cinema and commercial cinema. In art cinema you have to have these very long shots, and confront very serious issues where everyone is very sad all the time. And commercial cinema has to all be stupid comedies. I know this sounds very basic but I think it’s very dangerous to make these distinctions because on the commercial side you have a lot of conventions and a lot of leisurely ways of doing the same things. But I don’t think the critics are attentive enough to see that on the art side there are other types of conventions that verge on parody. That’s narrowing the spectrum of what can and should be done. But I like to laugh, and in France when you see films about social issues they are very realist, very victimizing—like the poor Arab guy can’t find a job because of his skin color. Which might be true, but I don’t need to see it in such a conventional movie. And it’s personal: as a spectator I like to see movies with certain contrasts. I’m not a big fan of realist, or naturalist, movies. From Hollywood films to Japanese, Italian, and Russia cinema, what’s always exciting is the relationship between the reality and something much more peculiar, which could be the colors, the music, the art direction, anything to bring out these contrasts.

Is it harder or easier to get these kinds of films funded than a drama?

I’m not really sure, but I do know that the comical aspects of our film weren’t a financial consideration. In fact, the script was much more comical. And I could have made a much more comical film in the edit. I cut a lot of very comical scenes. Not because I didn’t like them—they were quite good—but I thought they were dangerous because if there’s too much comedy in the first and seconds parts of the films it would be too difficult for the audience to be able to accept that change. The end of the film was almost experimental, because originally the change of tone was too radical—too arty even. It was very sudden. But it was also important to maintain this balance for the teaching side, because of the subject of the film: what is it to teach, and is there perhaps a relation between the difficulty of teaching and the importance of teaching? I thought that too many comical scenes could distract from these basic issues. Your schooling might be the most important thing in life, more important than your parents and family even. What makes you what you are when you are growing up is what you’ve learned. And it’s in school where you learn things. Not with your family.

I’m curious if perhaps there’s an unconscious effort on the part of French filmmakers recently to confront certain social issues through genre. I’m thinking specifically of Bruno Dumont’s turn to comedy and musical comedy, as well as Claire Denis, whose new film [Let the Sun Shine In] is something of a sex comedy.

I haven’t the Denis film but I have heard it’s a comedy. I never thought Claire Denis would make a comedy. And 10 years ago I don’t think anyone for one second would have thought Bruno Dumont would make anything related to a comedy. But I’m not sure why there’s been a turn. Those kind of directors can be very extreme, with serious, somber subjects, or tales of redemption, like in Life of Jesus or Humanité. It can be a joke, but it plays into what I was saying before: these filmmakers go to festivals, and those are the types of films that are bought and that you see at the major festivals. You know, the two-and-half-hour, serious [films]… by Haneke, Ulrich Seidl, Carlos Reygadas, or whoever. Maybe Dumont and Denis wanted to bring a little more life to these festivals. Again, I haven’t seen the Denis, but perhaps there is something to the turn. I read an interview recently with Olivier Assayas where he referred to Clouds of Sils Maria as a comedy [laughs], and said that his next film will be even more on the comical side. So we’ll see.

Can you talk about your appreciation for comedy as a genre at different points in your life—growing up, as a critic, and now as a filmmaker—and how it might have changed over time?

That’s a huge question. I do of course watch a lot of recent movies, but I think my taste by now is a little fixed, like the history of cinema is fixed. Except perhaps if you’re crazy, no one would dare to say that American movies of the last ten years are better than those from the ’40s or ’50s. For me, those movies are immortal—there were masterpieces coming one after the other. Now there are perhaps two or three good American movies per year. And I don’t mean that to sound disparaging. I think most people would agree there aren’t many good American films nowadays, especially from the studios.

I do watch a lot of recent comedies. Apatow, for example. But my favorite is still Lubitsch. Not even Apatow thinks he’s better Lubitsch. Nobody’s that pretentious. And the same holds for me. That doesn’t mean we stop making movies, or say, “Well there’s nothing left to do in comedy.” We shouldn’t assume we’re footnotes. Perhaps I’m wrong, but I hope my film doesn’t look or play like a revision or a revival—no one should look at it and say, “Oh that’s very Hawksian.” I’m not trying to imitate the masters. I actually don’t think my movies are very classical. They’re quite strange, even disruptive. So my taste are fixed, but not my methods.

Other than through genre, was there a certain approach you were hoping to take to these social issues?

In France we have a lot of racism. And the majority political party is right-wing… [Pauses] Let me use an American example. There’s this Clint Eastwood movie [Gran Torino] where he plays one of the last white men living in an Asian part of town. For me Eastwood sometimes has a heavy touch, like in Mystic River, concerning big problems, like pedophilia or whatever. But in Gran Torino, because of this racial disparity, he uses a kind of humor and lightness. Especially in the collective scenes, the family situations, where he’s the minority. And it’s not only in the social aspects. There’s also a palpable pleasure on the part of Eastwood that exudes something fresh. Eastwood’s recent movies are not usually very fresh. There’s something much more immediate to that film.

For my film, to have Isabelle Huppert confront an almost totally non-white class generates a new way of interacting. A lot of things the young people say in the classroom scenes were improvised by them, and their words, even though they’re harsh and can be anti-Semitic, are very funny. I never would have thought of these jokes—this is humor straight from the French suburbs. When you watch a movie what’s exciting is seeing someone change. If you’re teacher in an upper-class, white high school in the center of Paris, if one of your pupils becomes genuinely interested in what you say, perhaps that’s a victory—but it’s not a huge victory. In my movie, it’s a worst case scenario: you’re in the suburbs, with bad teachers and students who aren’t dedicated enough to stay in a regular high school. It’s like a war movie or an action movie: the more powerful the thing is that you’re confronting, the more valuable your victory will be in the end. The scene with Isabelle and Malik in the laboratory is a good example. She’s trying to explain a proof, and he finally becomes interested in science and she, for the first time in her life, is able to successfully teach something.

What I don’t like about films about school in France is that they don’t concentrate on the teaching, and if they do it’s comprised of two lines of dialogue and then it’s on to another thing. If you’re going to make a film about the difficulties of teaching, you must have scenes with someone teaching! Like in The Wild Child, by Truffaut, it tries to say something about the difficulties of teaching, perhaps the most extreme difficulty of teaching someone who’s been living in the wilderness. In my movie, Malik is able to speak, he’s able to read, and he’s able to write. What he’s missing is the reasoning, the critical thinking, when you can insert a “therefore” between sentences, or a “thus,” or an “I conclude that” to finish an argument. Not only saying things one after the other, but finding deductive relationships between sentences—the verse of logic.

Your editing style fascinates me. Scenes often times seem to linger a beat or two after jokes, or sometimes cut off quicker than expected, holding back potential laughs.

Yes, that’s true. I’m very sensitive to the rhythm of the film, but I’m not trying to make something fluid. For example, I love Jacques Tourneur movies. But he has a very sweet and soft style—there’s an almost grayness to the editing, where you don’t feel the punch of the cuts. I’m looking, again, for something more contrasting and disruptive. A calm shot with an abrupt cut can offer an adrenaline rush. But I try not to approach it in a systematic and thus boring way. I’m trying to find a musical flow between shots, to keep it exciting without sacrificing quiet moments, or pauses. In Tip Top it was quite different, more erratic, more in your face, leaning on the cuts. In the third part of this film I tried to have very short, almost sketches of scenes, and in between have these huge blocks, like the long teaching scene with Isabelle toward the end, which is like 10 minutes long, whereas the scenes before and after are like one minute.

But it can be risky. Even my producer was scared it was unbelievably boring to hear her at the end of the film giving a very abstract lesson on interaction. But this scene for me is not like the laboratory scene. Because here the pupils don’t understand. What’s essential is that she conveys that she cannot continue, and that what she says moves the young people. What I hope is that the audience is also moved by the end of the scene, even with the aridity that precedes. So the emotion you end up getting is not soft, tender, or melancholic—even the emotion has an aridity to it. I hope you’re moved, especially when the student cries, but because of this long speech I hope that the emotion is arid, direct, and dry. You know what I mean? [Punches hand in the air] Severe emotion.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs the experimental screening series Acropolis Cinema and is co-artistic director of the Locarno in Los Angeles Film Festival.