Interview: Ruth Beckermann

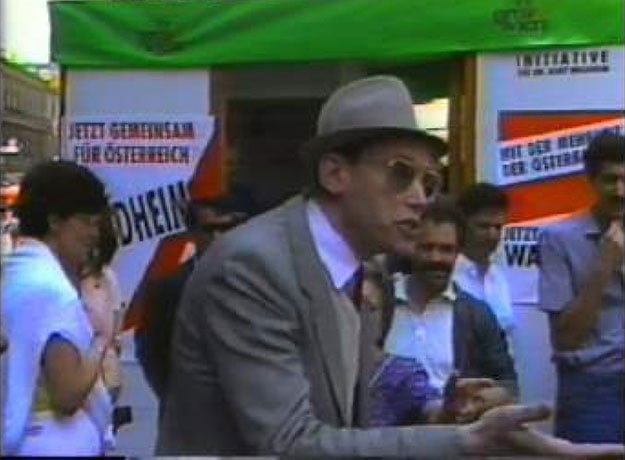

Following a nine-year stint as Secretary-General of the United Nations, Kurt Waldheim ran for President of Austria in 1986. During the fraught campaign, in what’s come to be known as the “Waldheim affair,” journalists started to question Waldheim about a curious seven-year gap in his autobiography, during which it was rumored that he served as both a member of the SA and an ordinance officer in the Nazi Army—facts that Waldheim spent the next several years of his life initially dodging, and soon enough outright denying.

In her work over the last three decades, Austrian filmmaker Ruth Beckermann (recognized most recently for the luminous epistolary drama The Dreamed Ones) has consistently merged the personal and the political through a variety of docu-fiction devices. Beckermann not only lived through the Waldheim affair, but captured much of the ensuing protests as a young radical with an interest in then-nascent video recording technology. Returning to this footage thirty years later, Beckermann was struck by its modern day parallels, not only with the current Freedom Party of Austria–Austrian People’s Party alliance, but also its larger resonances with the rise of nationalism, “alternative facts,” and the Donald Trump administration.

Combining this first-person footage with archival material drawn from the internet, court hearings, press conferences, local and international television coverage, and voiceover from Beckermann herself, The Waldheim Waltz is a striking, occasionally shocking, and all-too-familiar document of a powerful man using the media and the power of influence to his own selfish ends. Functioning like a ticking-clock thriller despite the well-established facts of the matter, Beckermann’s film is a coup of personal-political archeology. As a call-to-arms for anyone with a recording device to take to the streets and document history as in it unfolds, her film succeeds as a reminder that the resurgent right (in Austria and elsewhere) would rather sweep such atrocities under the rug of history than confront the repercussions. As a weaponized piece of nonfiction storytelling, it restores attention to an era that, as seen in other recent feats of cinematic excavation such as Sergei Loznitsa’s The Event (2015) and Andrei Ujică’s The Autobiography of The Autobiography of Nicolae Ceausescu (2010), carries disheartening yet crucial similarities with our own current climate.

Following The Waldheim Waltz’s premiere in the Forum section at the 68th Berlinale, Beckermann sat down with Film Comment to discuss the project’s protracted gestation, her family history and personal relationship with the politics of the era, and the process of familiarizing yourself and connecting with footage you didn’t shoot yourself. The film is currently available to stream on Festival Scope for free, and the Arsenal in Berlin screens a Beckermann retrospective April 19 to 27.

Can you take us back before the events depicted in the film. Do you recall your first memories of Waldheim as a politician, and how he was perceived during his tenure as Secretary General?

Very superficially I simply perceived him as Secretary General of the UN. As I was born into a Jewish family, my parents didn’t like his politics—and the politics of the UN were not his politics. At that time I became very critical towards the Jewish community and my parents and became quite an activist: I was politically interested in the case of the PLO, and in the reconciliation between Israel and Palestine. At the time I thought the politics of the UN were quite okay—but everything’s complicated! [Laughs] But I didn’t perceive Waldheim as a particularly interesting personality at all. He was always a functionary. But what was terrible was the way he reacted to the Entebbe case in Uganda [in 1976], when Palestinian terrorists hijacked an Air France plane [and the Israeli Defense Force proceeded to free the passengers]. He said something like it’s not okay to intervene in a foreign country.

But [by the time he was running for President of Austria] it was obvious he would win the election. The socialist party didn’t even want to come up with another candidate, since he had been Secretary General and he was so well known—“the man we trust,” and so on. So even before the delegations it was clear he would be the winner, and he was in the end.

You lived much of this story, documenting many of the events we see in the film. What was your original intention for documenting the protests, and what was your plan for the footage?

This was the beginning of video, and someone I knew had this camera and so I started documenting it for us. But I did have a reason and that was because the state TV didn’t document us, the people, at all. They ignored us. So it was very important to film from our perspective. But I had no intention to make a film.

Was your mindset to document this moment for historical purposes?

We didn’t really think like that. It was just to document. But I did use some of the footage in another film of mine. At the time of the Waldheim affair I was in the editing room for a film, [The Paper Bridge], about Austrians and Jews, and Jewish identity, which was not at all about the affair. But as it occurred I put a couple of minutes of this footage into the film, like a break, as if to say, “It’s still going on today,” this outbreak of anti-Semitism. This was in 1987, a year after the Waldheim affair. At this time the Waldheim news was all over the United States, so I toured with this film all around U.S. universities and cinemas.

What was the impetus behind revisiting and compiling the footage for a film now?

Well I started to work on this project in 2013. I’m not sure why. I just took out these VHS cassettes and started to look at them…

And you hadn’t looked at them since?

I had no reason to! [Laughs] But as I looked at some of it with my assistant at the time, we said to each other, “This is really shocking.” It was more shocking than it was at the time. Then we found on YouTube other footage of Waldheim and the affair and we edited together something like 20 minutes and showed it to my son and some of his friends—other young people in their twenties. And they were so interested in it. They said, “Make a film, make a film of this!” But I thought, “Why should I make a film? I was part of it. I know it. It’s boring for me.” [Laughs] It’s interesting: when you’re a part of something like this, you’re only a small slice of the cake. But to watch this international footage and see the different angles and perspectives and put it in a larger context was good for me.

Other than the footage you shot yourself at the time, and what you found on the internet, how did you go about finding and compiling the material we see? And how did you go about structuring the film?

The internet was only the beginning. At first I worked a lot in the Austrian archives, because it was the easiest and they had the most material. And I saw a lot—I can’t tell you how many hours. I think it was four months of just going to the archives. And I selected a lot of interesting stuff. But then I took a break and made another film, The Dreamed Ones. It wasn’t until 2016 that I continued with this project. And from there I ordered footage from the state, and went to the BBC. The French archive is actually online—it’s great. You can watch everything online. But just the footage I ordered was something like 200 hours. Throughout the summer of 2016 we watched all this and began to reduce it. But from the beginning it was clear to me that I didn’t want to use interviews, or shoot [new footage] myself. It was only then that I began to come to this chronology of the three months leading up to the election—which is kind of a mechanical device that allows to have associations and excursions, and to still come back easily.

The time-based structure seems to add a bit of suspense to the film, even though the outcome is preordained.

Yes, that’s so interesting, because at the premiere here [in Berlin], I’m sure that most people knew the outcome. But when they read the last title card, saying Waldheim won, there was a big gasp, “Ohhhhh!” And then a sigh, like, “He really won.” [laughs] It’s interesting the effect that movies have, even if you know everything [about a subject], you still hope there will be a happy ending.

Was there any footage you came across that surprised you?

I wasn’t surprised about him, because I remembered well that he never really said anything [to indict himself]. But for instance in the British footage where he beats his fists on the table and they show this close up—that was shocking. I had never seen this footage before. That interview made him become very emotional. The interesting thing to me was how the different television stations approached him. Austria protected him. You see these Austrian journalists who are more than polite. But what really surprised me and that I’m really happy that I found was this footage of Waldheim’s son at his hearing. Usually they only keep what’s related to the subject, which means you have to work with very short clips. But in this case they kept the whole hearing.

How do you feel about his son? At that hearing he’s obviously defending his father, but at that point we’re well past the point of believing everything we hear.

I’m not sure. What do you think?

I’m not sure either, but it seems to me he probably knows more than he’s willing to let on to protect his father and his family.

Everyone in his family is so different. I think he believes his father. I don’t know if he would be able to defend him if he had doubts. For me it’s strange that he doesn’t have doubts!

He wants to believe him, that’s for sure.

Yes, definitely. There’s even a moment when I felt pity for the son, because he’s so devoted to his father, and this congressman really attacks him. But it’s his fault: why did he defend his father in that way, when nobody asked him!

What was Waldheim’s eventual administration like? What happens after the film?

Not much. [laughs] He wasn’t invited to any Western countries. He went to the Vatican, to the Pope, and to some Arab countries, but that was it. He wasn’t visited by any Western chiefs of state. He sat in his villa for five years. Very strange. For Austria the affair was very good, because so many discussions then went on, and Austria’s image of itself changed—its attitude toward Waldheim’s past changed. Suddenly this taboo was broken, this taboo of officially telling the world that they were the first victims of the German Nazis. And always with this wink of the eye, saying, “We know that it’s not true.” That was my childhood.

At one point in the film you say in voiceover that you can’t protest and document at the same time; you have to choose one or the other. Is this film an attempt to reconcile that notion? There are certainly contemporary resonances to the story.

Waldheim was avant-garde for his time. Mr. Trump should see this film. But he’s a very different personality to Waldheim. I think the psyche of Trump is very easy to understand compared to Waldheim. If Waldheim had said, “I’m sorry I omitted these years from my autobiography,” I think people would have understood. But he was unable to do that. It’s an enigma for me why. I think he was such a stiff character, and so stubborn.

How did it feel to see footage you shot so long ago that you might have never seen again?

Shocking. But I was proud of myself as a camerawoman, shooting right in the middle of all those people. There’s this moment where everyone is shouting, “Waldheim, no! Waldheim, no!” and all of a sudden I make this pan to a guy who says, “Waldhem, yes!” This was a good move! [Laughs]

But it was the found footage that was most difficult. It’s so different than working with footage you’ve shot yourself. It took me a long time to connect with this footage. You don’t know who shot it, who were the journalists, who were the editors. It’s very anonymous. It takes time to take to make it your own.

Jordan Cronk is a critic and programmer based in Los Angeles. He runs Acropolis Cinema, a screening series for experimental and undistributed films, and is co-director of the Locarno in Los Angeles film festival.