Interview: Paul Harrill

Paul Harrill makes films for adults. Over nearly 20 years, Harrill has written and directed a handful of shorts and a pair of features—his latest, Light From Light, premieres this week at the Sundance Film Festival—that aren’t what we typically associate with “adult entertainment” anymore; the films have no nudity or graphic violence, and rarely even a curse word. Instead, his work is genuinely mature, exhibiting a sensitivity to character and emotional intelligence that’s increasingly rare in American independent cinema.

Harrill’s return to Sundance has been a long time in the making. After his first short, Gina, An Actress, Age 29, won the festival’s top prize in 2001, Harrill honed his craft on additional short projects—including Quick Hands, Soft Feet (2008), featuring one of Greta Gerwig’s first performances—and spent time teaching film (at Temple, Virginia Tech, and now University of Tennessee, Knoxville) and programming (at Knoxville’s Public Cinema). Of particular interest to Harrill is the rich tradition of regional cinema in the U.S.—narrative films made between the coasts with small crews about the lives of people ignored by the mainstream. At Knoxville’s Big Ears festival last year, he curated “A Sense of Place,” a retrospective of American regional film that included hallmarks like Herk Harvey’s Carnival of Souls (1962) and rediscoveries like Penny Allen’s Property (1978).

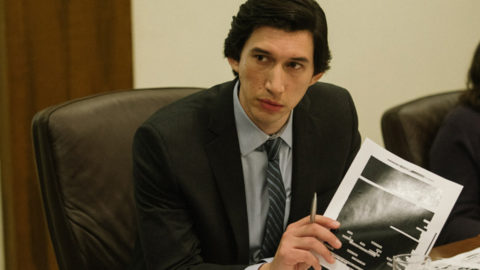

His two features—2014’s Something, Anything and now Light From Light—engage directly with this tradition. They’re sister films, both shot on location in East Tennessee and about “ordinary” women who find themselves in spiritual crisis, caught in lives that lack something intangible. Whereas Something, Anything’s Peggy turns toward a monastic lifestyle, Light From Light’s Shelia (Marin Ireland) is a single mother who moonlights as a freelance paranormal investigator. She meets recent widower Richard (Jim Gaffigan), and tries to help identify whether his late wife may be haunting his farmhouse. When attempting to contact the spirit, Shelia intones, “If you wish to communicate, let yourself be known”—and that is the chief subject of Harrill’s cinema: people who struggle to let themselves be known.

A movie of great intimacy and mystery, Light From Light is a remarkable achievement. On the occasion of its debut, I spoke with Harrill about the responsibilities of the regional filmmaker, engagement with the supernatural, and crafting non-romantic love stories.

Light From Light (2019)

The history of American regional cinema is important to you, as a filmmaker, a teacher, and a programmer. Can you talk about your first encounters with films in this mode? Which have become particular favorites and inspirations?

Probably the earliest encounter would be Tender Mercies. I think I first saw it in high school on VHS. What struck me about it was that the pacing felt real to me. It had a pacing that I associated with real life. But my interest in regional cinema really deepened after I moved away from the South for the first time, when I moved to Philadelphia for film school. The interest probably came out of two things—one being a kind of homesickness, the other being a desire to process what it was like growing up in the South, to understand what made it different. Because it had always just been the thing I knew. So it’s around that time that I discovered films like A Flash of Green and David Williams’s Thirteen, which is one of the great forgotten films of the ’90s. It wasn’t until a little later—with restorations or so on—that I got turned onto some of the films we think of as landmarks like The Whole Shootin’ Match, One Potato, Two Potato, Northern Lights, and others.

A hallmark common to many of those films is non-professional actors, but with Marin Ireland and Jim Gaffigan, you’re working with trained performers. How do you go about integrating them into this specific world?

There are great regional films who have used professional actors. I mentioned A Flash of Green, and Ed Harris is fantastic in that. Or Tender Mercies, which is one of Robert Duvall’s greatest films. But when I first started making films as a student, I wanted to work with nonprofessional actors. As I grew as a writer, I came to this crossroads: I either needed to start working with performers who had training, or I needed to scale back what I was asking of the non-professional performers in the writing. So I made a choice, and that was to start working with professionals.

When I’m considering an actor for a role, it’s ultimately a gut thing. The test is really: would I believe this person as this character, and in this world? It helps when the performer sometimes has a connection in their own life that extends to the material—whether it’s where they grew up, or the way their own family situation connects to the character’s, or maybe it’s even that a loss or challenge in their own life is similar to what a character has been facing. If you can find a talented actor with that kind of connection to the material, it’s the best of both worlds. You have someone with the range and ability you expect from someone with training, but you also get some of the actuality that a non-professional might have brought to the character.

It’s delicate, and the decisions have to be very precise.

It is. Casting took some time with this film, and that’s because we had to get it just right. And I was lucky to be working with producers who understood and supported that. In fact, it was Elisabeth Moss who first suggested I consider looking at Marin’s work.

One other thing that is maybe worth noting, with regards to the regional stuff, is that we made a decision early on: we’re not going to do accents. There are different East Tennessee accents—some are really specific and hard to pull off, and then some people don’t even have a strong accent. But more importantly, an accent, to me, is not the marker of authenticity of a performance in a story that is regionally specific. The accent is not the thing. I’d rather have an actor not try to do an accent than for them to get it wrong. Because then it’s, “oh, they’re acting. They’re trying to play someone from the region.” You can see the mask.

Light From Light (2019)

There are almost two strands in regional filmmaking: movies made inside the community, but also carpetbagger filmmaking, for lack of a better term. I love many of those movies—I’m thinking of something like The Last Picture Show—but it’s a very different method.

That’s the funny thing about Tender Mercies: it was directed by an Australian. I don’t think a filmmaker has to be from the place, live in the place, to tell a story that’s compelling and respectful about a place. As a director, you’re always trying to find a way into the material—there are just different ways to do that. I don’t have an axe to grind with movies that take that approach

It raises questions about who a film is for.

I definitely am thinking about an audience, or audiences, as I make the work. People who are interested in art films, in the broadest sense of that term, are one audience. But I also want to make a film that people in my family would watch. If you’re making a film about a region, I think it’s important that that film can connect with people who live there, or live in other areas that are similarly underrepresented in movies. I’d like to think that the movies I make would appeal to people like the characters I’m telling the story about. These aren’t folks that art films are marketed to. And that’s because marketers and distributors make assumptions about people because of where they live, their class, their education, and so on. I know my films aren’t for everyone, but I want people with different backgrounds and interests to find them approachable. That’s something I think about a lot in the writing, and definitely a lot in the edit.

That sense of place is very important, but it’s often established through the subtlest and most efficient of means: less through panoramic establishing shots than specific choices in the dialogue, the production design, the costuming. What’s the process of culling and presenting those details?

I’m glad that comes through. With regards to production design or costuming, that may come out of the fact that I always take little notes about things I notice in life—an object, something I see someone wearing, or whatever—that could maybe help reveal character or be part of a story. Then, when I’m working on a script, or if I’m in pre-production, if one of those details seems relevant or organic, it’ll work its way into the story. And of course the people I’m collaborating with bring their own ideas to the conversation once we’re in pre-production. In this way, it’s helpful to work with people that know the region—or areas like it—because they want to get those details right. And like me, those details come from personal observations, not things they see in other movies.

With dialogue, I don’t sit down and think, “I need try to write dialogue that sounds true to East Tennessee.” I work a lot on the dialogue to make it sound real, to have rhythms that sound like conversation. But I’m not consciously thinking about it as a regional thing. I’ve spent a long time in that region—so a lot of it’s just the way I talk or the way my friends and family members talk. So I have a self-awareness that that’s going to come out, but it’s not explicitly self-conscious.

Light From Light is in dialogue with genre cinema—it’s literally a ghost story—but really just uses those elements as a means to arrive at other interests and ideas. I’d like to hear about that balance, for example, if there were versions of this story that had more (or less) engagement with the supernatural.

“Ghost story” so often means “horror film” and I knew from the beginning I wasn’t interested in doing that. There was never a version that ventured into that territory. One friend who’s a big genre and horror fan was so angry after reading an early draft of the script because he felt like I left all these chips on the table. In terms of the supernatural, it was something I thought about a lot when I was taking notes for the script. Part of my writing process is jotting lines of dialogue, or even conversations, even before I understand who’s saying the line and what the context is. There were a couple of lines that became ways into the film. One was, “People think ghosts are scary. I think it’d be wonderful if they were real.” And then another was when the radio interviewer asks Shelia, “Are you a believer or a skeptic?” And Shelia ultimately says, “I don’t know what I am.”

When I uncovered who was saying those lines and in what context, that’s when I first started finding the balance of the human story with genre and the supernatural elements. The story is about two characters that are trying to figure out what to believe and how to live with their pain, their loss, their fears, and their regrets. The supernatural is part of that. But it also extends beyond that. So it began with the writing, but it was a continual process during filming and editing, during the sound design and scoring, of trying to find the balance I was after.

Something, Anything (2014)

Instead of horror, I think it’s closer in spirit to several films you’ve cited as major influences, like Love Affair or I Know Where I’m Going! or Borzage’s work. Something, Anything and Light From Light have an intensity of feeling similar to those films but aren’t about romantic love per se.

Those movies are really important to me. I’d argue that both of my features are about love, just not necessarily romantic love. They’re about connection. And they’re about loneliness. I think that’s at the heart of those films you’re mentioning. In Love Affair, the separation that’s happening in that movie and the sense of disappointment in that movie is very strong, and I really respond to that. Something, Anything and Light From Light are—to me, at least—movies about people who, by the end of the film, are ready to love and be loved. Who’ve grown in the way they can give love. They’re films about people that have processed the loss of love. So in that sense, I think they’re very much love stories.

They’re also both about seekers, women who find themselves in spiritual crises and search for answers or solace. How do you go about figuring out a character who doesn’t have herself figured out?

For both films, people I know served as inspirations. But it’s never one person. With Something, Anything, it was some specific women I grew up with, and maybe a couple of students I’d taught. In the case of Shelia, it was a few different women I know, who have raised kids on their own. And one who has explored, in her own way, some of the same questions Shelia has. But there’s a lot of me in these characters, too. I’m certainly someone who has unanswered questions, someone who has felt lost, someone who hasn’t found, as you say, solace. So I connect with Shelia at a pretty deep place, even if she and I may live out our questions in different ways.

But I don’t claim to know everything about the characters. The deeper you get to know someone in real life, the more they also grow in their mystery to you—at least sometimes. It should be that way with fictional characters, too.

C. Mason Wells is the Director of Programming for New York’s Quad Cinema.