Interview: Laurie Anderson

Loss and grief were a running theme at this year’s New York Film Festival, not least because of Chantal Akerman’s untimely passing. Laurie Anderson’s Heart of a Dog broaches these topics—as well as terrorism, surveillance, creativity, technology, Anderson’s childhood in Illinois, and the act of storytelling—in the artist’s characteristically vernacular, eccentric style. Rather than offering up pointed lessons learned after the deaths of her mother Mary Louise, pet rat terrier Lolabelle, and husband Lou Reed, Anderson instead reflects on mortality through personal stories that are never over-sentimental. A true multimedia artist, Anderson incorporates a variety of film formats and digital effects to take the audience to places that are otherworldly yet familiar.

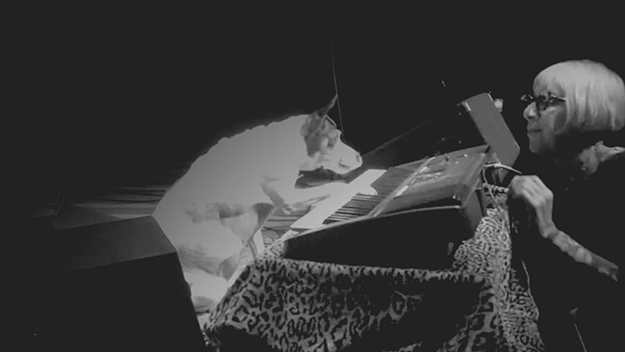

Heart of a Dog opens October 21 at Film Forum, following its screening at the New York Film Festival and a few weeks after Habeas Corpus at the Park Avenue Armory. FILM COMMENT’s Violet Lucca spoke with Anderson on the grass lawn that overlooks Lincoln Center’s Hearst Plaza, during magic hour. “I’m glad I’m not a Juilliard student,” the award-winning artist mused on her surroundings, with her customary empathy. “They’re worried, you know? There’s a lot of pressure.” The same didn’t hold at all for her regarding the interview: “I love talking about the film because I’ve learnt a lot of stuff that way.”

As an artist who has worked in so many different mediums, why did you choose to make this into a film?

You know, it hadn’t even occurred to me until a guy from Art in America got in touch with me and said, can you make a film about your philosophy of life? I said, no way! He came to a show about my dog—I started there. I worked on the film. I stopped for a year. I went back to it and turned it into short stories. I expanded it. Contracted it. And this is a film about my philosophy of life, in the end. They tricked me into this!

That was the show with Lolabelle in the Bardo? [Forty-Nine Days in the Bardo, which premiered at The Fabric Workshop in October 2011.]

No. It was a show called… let me think. Boy, I hate titles. I hate coming up with them and I hate living with them. Anyway, it was a collection of stories about… stories about stories, in a funny way. And that was how this project began. Because I started thinking, how are they constructed? And who’s talking to who? And why are they telling that story? For example, I ask you what you were like as a kid and you tell me a story of “I was shy” or “I was…” How are you framing that? What function does it have in terms of your own identity? Is it even true? I guess the only person who wants a longer answer when they ask you to talk about your childhood is a shrink. And then you really do get a chance to go “Who am I?” But mostly, we use [stories] as shorthand. No one really wants to know how your day was. No one actually wants to know. It’s fortunate because it would take all day to do that kind of exchange.

Anyway, in the middle of this film is something called “A Story About a Story” and it is one of the childhood stories that I had about breaking my back and what happened and how I remembered it as a punk and then one day remembered it through a hallucination of sound, almost. I was trying to describe the experience to someone of being in the hospital with a lot of kids dying and I suddenly remembered it through sound. I remembered it through how the hospital sounded. And I was like, ah! And it was breathtaking because I’d forgotten it. That was a situation in which the more I told the story, the less real it had become. When I remembered it through hearing, I thought, oh, whoa this is like what the book that is at the center of this movie, The Tibetan Book of Dead, called the great liberation through hearing. You need your full set of senses to figure out who you are and where you come from, and I don’t know if I can figure out where you’re going, probably not.

Did you refer to any particular texts besides The Tibetan Book of the Dead while you were coming up with the structure of the film? All of your work is based around language and telling stories.

It’s really a collection of short stories, is what it is. There are stories about surveillance culture, some of them, and there are stories about my past: some about the things I observed around me, and some are made-up scenes. I ask a lot of the viewer in this. You’re not gluing to a hero, and identification isn’t really what this is about. It’s almost about quite the opposite. You’re asked to see something through a dog’s eyes and then through the lens of a surveillance camera and then you’re floating around bodiless in the Bardo. Who… what are you doing here? So I do in a sense ask for a lot of flexibility from the viewer. It’s a really challenging movie to see from that point of view.

I also hope that some people who can get into that groove are fine with it. And other people are like, “What’s the story? Is this a shaggy dog story?” And most of the stuff that I’m doing is “Oh and that reminds me of this…” However, the construction is that these stories have ways of illuminating each other, and they develop and spiral out from each other through various themes of how we see, how we hear, how we remember, and seeing all of those scenes through the filters of love and fear.

Sometimes I wish I would stop talking… It’s just going to sound so ponderous, stories about my dog. My favorite things about it are things that are almost like paintings, with rain sliding down a surface, and I also like the things that are, in a way, real, like the street scenes and the things we got to shoot. We shot most of this within a block or two of where I live. So it was sort of satisfying in that way too.

Goya’s The Dog

There are lot of digital effects in the film—I’m thinking of the gold pattern that’s reminiscent of Goya’s The Dog, the painting you mention in the film, and then also the weather effects, because it gives the image a kind of texture. Where did that imagery come from, in both senses?

When I was in Venice, I realized where the gold came from, because I went to the Doge’s Palace and saw all these medieval paintings, and the sky was gold. It was the color of the infinite. I mean, they just also liked working with gold because it made these paintings more expensive and they could charge more. I started as a painter, and this is like painting. So, of course I had to add the Goya painting because it’s one of my favorites. Boy, he’s one of my favorite artists! I have ended music tours in Madrid so that I could spend a week by myself at the Prado, just going from room to room, and the Goya rooms were my favorite. But this is a crazy one because it relates more to his architectural, decorative work, when he would have dogs and lions and things curling around panels and making kind of trompe l’oeils.

But I don’t know what the meaning of the dog is. For a lot of scholars it’s very mysterious. Who is this dog? Is he running behind a hill? Is he drowning in a brown wave? Where is he? I just love this little animal and, of course, I chose dogs, not just because I love them, but also because they have the skill of empathy, which I wanted to make that a big part of this film. They like to study people. We’re their food supply, so they have a good reason to study us. But I think they also admire us. I think one of the biggest reasons is because we invented cars. I think they really can relate to that. Sticking their head out of the window, the wind blowing through the ears. They love speed—it’s awesome, man. And so they stick with us. And they’re like “Okay.” So I like that attitude.

I like liking things. I like liking people. I like trusting them and trying to find something that is pure in them. Because I do believe we all have that. I was having a conversation with Louis CK last night, and he said that when he meets people who are mean to him, he realizes how sad they are. He said: “I’m really nice to people when I’m in a good mood, and when I’m not, I’m not nice to people. And so I just try to make them laugh.” What a wonderful thing, to try and get beyond their misery or their perceived misery, which is the same thing.

The snow and the rain are another piece of beautiful imagery in the film.

With the snow and rain, I wanted to make a barrier in the middle of the film that was another world, one that we can’t quite reach. This was the description of the Bardo, the 49-day period that Tibetans believe happens after death. They describe it as the period during which your consciousness dissipates. Your energy is the same, but it turns into another kind of living form. It’s just like the law of physics that states that energy can’t dissipate. So you’re still alive, just in a different form. I thought that is really fascinating. But it’s so outside our realm. So I put it in a box in the middle of the film behind glass and water and light and said, here’s an idea that Tibetans believe could happen after this brief experience that we’re having here.

[A girl nearby on the lawn begins singing.]

See? Juilliard student.

You gotta love them.

Speaking of music, how did you make decisions about the music that you included?

I had more or less finished the film as a pretty good rough cut, and it was only voiceover. I screened it for some people and they said, “Don’t put music on this! This is perfect like this. It’s so hard core. No music! Don’t try to play those cards!” And I was convinced of that for a while. Then I was at a place in February where I had some time and I thought I’m just gonna put this up and play violin along with it and see what happens. I mean, I’m a musician, so I thought, I can always take it off! It doesn’t hurt to just try. I tried and I liked it. It’s just another voice. I like the polyphony against the rhythms of language. It’s non-stop talking. There’s only a few seconds when this person stops talking! So for some people that’s like, it’s a lot of words.

There’s so much bad autobiography out there right now—or at least I feel that there is. How do you know which parts of your life to include, and when do you know when a piece is finished?

This is not really autobiography, although there are things about myself. It’s not a film about “I want you know how I am.” You don’t need to know. These are stories about how we move through time, really. So I used my own experience in that way, but it’s more to create a kind of conversation than to say, “Look at me! It’s not about Look at me and who I am.” So I hope that gets absorbed in all the questions that are here. Because the film is full of questions. The main one being: “What do you want?” and “Where are you going? Is there something you’re going toward? Is it a pilgrimage? Toward what?” So it leaves you with that.

It’s the questions that are on my mind all the time. And I don’t have the answers, and I wouldn’t want to put them on other people. One has their own way of going through time, and when you think about it in certain ways, all of those big questions are things that religions are trying to answer and try to explain. Not so much God as Time. Where do we come from? Where do we go? How does that work? What is infinite? What is eternal? This is a secular version of asking those questions. I don’t have an axe to grind. I don’t have a thing that I’m selling. In that sense it is more investigative of how all those stories get told. Even the really big stories we all sort of live by. One of the big stories now is that the world will get hotter and hotter and then we’ll drown. Or: technology is gonna save us and we’re all gonna be robots really soon. You know? In a way you take those stories for granted and you start filling them in. And those are really interesting to me, so I try to look at that.

In the Nineties, there was a vogue for artists doing CD-ROMs, and you did Puppet Hotel, which was a great one.

It’s coming out as an app! It’s not graphically refined enough to come out in a bigger format, but it looks good in the iPhone. And it’s fun. It’s really fun.

Do you have a desire to explore that medium?

I do, absolutely. I geek out in a lot of things. I really enjoy technology. But it’s not at the top of my list right now. The top of my list right now is to do big landscape paintings. I just need to go into a more bucolic thing that doesn’t involve any buttons.

I don’t trust technology particularly. It’s all just a tool for me. I don’t think art is better if it uses technology at all. You can do super-dangerous things with a pencil. And super-idiotic things with massive amounts of information you’re tossing around and it’s just a waste of time. In fact, a lot of that stuff is just a machine going through their paces. And, I mean, I know machines are fast, thank you very much. Good for you.

What is, at present, your favorite technical tool to use?

I’ve been having a lot of fun with clay lately. But you asked technical… so: scalpels. Clay scalpels. They’re pretty technical. They’re tools. In terms of technological stuff, we did something at the Park Avenue Armory the last few days and that was super-fun, very challenging technology, making a three-dimensional film and screening it live over continents and then crunching the numbers to wrap it onto another surface. We geeked out in that, for sure. It was fun to try and make that work. I really enjoyed that from a technical point of view.

The text that appears on screen in Heart of a Dog is from your diary during Lolabelle’s 49 days in the Bardo, correct?

Yes. It’s a program I invented called Erst. I was working with the Kronos Quartet and they said: “We want to tell stories.” And I was like: “Why? You’re such great musicians. Why don’t you just play?” But then I thought: “Why am I saying they shouldn’t do that?” So I said: “Why don’t I invent something so you could tell stories with your instruments?” And they were like, yeah, great. And then I was like: “I don’t know how to do that.” But I worked with a designer and we came up with something that triggers words really fast. Generally, subtitles are super slow. When you’re looking at words versus images it’s a very different tempo. You see the words “She ran on the road.” And then it takes about 30 bars to sing that [singing] “Sheeeee…raaaannn…” and you’re like: “What is the relationship between the word and the note?” Not to mention the action on the stage—like when they do subtitles on operas, for example. And so I thought maybe I could find a new way to relate to an image to the tempo of the film [by making text appear on-screen, triggered by voice and music]. Do language like the way we think language. I wanted to try to imagine unvoiced language. What is language that is running through your mind? Looped words. That’s how I wrote that stuff [in my diary]. Almost unconsciously writing as fast as I could and then seeing what’d come out and then actually playing that with a violin and into the text machine, so that’s why it’s paced like that. So it’s like blahladadeddlydah.

What’s really fun is when you say one thing and read another. When you trigger it with vocals, when you trigger it with words. It’s beyond fun. Because you’re doing what you’re doing all the time in life: you’re having a conversation but you’re thinking of something else, and you’re looking at your phone and you’re doing a lot of other stuff. So you’re asked to process what you’re hearing and what you’re reading, and it splits your brain in half in a really interesting way. I try to do that live sometimes. But in the film, of course, it seems like it’s probably edited but it’s actually triggered [by my voice and with the music].

I read that one of your siblings had found a lot of 8mm home movies, which are presented in the film in a dreamlike and distorted fashion. What did you do to achieve that effect?

I slowed it down. That’s all I did to that thing. What happens when a film has been in a box for decades is that it starts warping and gluing together, and you start to see all the cuts and all of those artifacts, which when they are slowed are so impossibly beautiful. I just looked at them and went, oh my God! It looks to me like the background of a Bruegel painting or something. It’s so fuzzy and blown out and dreamy that it becomes a world where you can kind of… well, the relationship of text to image in this film is interesting because a lot of times when the voice goes on and on and on all you see are tree branches or telephone poles. But the story in the film is about a guy who lives in the trees [and works on telephone lines] and how people in that small [Illinois] town treated him. But you’re never seeing anyone. What I love about that is freeing people’s imaginations to build that person themselves. That’s why when I use imagery in live shows I try to keep it down. Not to the point of wallpaper, because every musician now has to use video and it’s just wallpaper, which can also be very beautiful and you can make anything work, but a lot of the wallpaper stuff is kind of meaningless stuff kind of back there for reasons I could never figure out. So I like to use it for counterpoint.

When I did put the music on, it was all strings because the producer of the film, Dan Janvey, said: “Don’t do any beats. Do strings.” And I was like, okay. But then I realized why movies are mostly orchestras, mostly string stuff. Because as soon as you put a beat in, you start relating it to the cut, and when you have strings oozing over the cuts, streaming over it in this free way, your eyes are freer to be rhythmic. You look around the frame in different ways. You relate to the cut in a different way. It’s fascinating to me. As soon as I put a beat in, it looked like a music video. I was like, “Get that beat out of there!” Too tyrannical.

I watched Home of the Brave again recently. It’s funny because you get the feeling that whoever funded Home of the Brave thought it was going to be another Stop Making Sense, but it’s so much more avant-garde, a lot bolder.

It’s weirder. They’re very different. David and Jonathan’s film is a really great concert film. And they’re not trying to do anything except show the joy and beauty of people moving and singing. I love that. It’s a really successful film. And Home of the Brave was just a different animal. Our music are different animals anyways. And that’s the great thing: there’s so much room for individuals to make different-looking and -sounding things.

The other thing about [Heart of a Dog] is unlike films from that era where you needed big crews, you can make a movie all by yourself now. My little movie was in the Venice Film Festival, and it was probably less than lunch budget for one day of any of the other films. I’m not trying to say that makes it any better or worse—it just makes it different. It does mean however that you can make a film for next to nothing. So it opens the field. It’s not like it was in the Eighties when you had to get a director and a camera crew and lights… Now you can go out with your iPhone. You can go out with your 5D and you can make a movie. And people will accept it as a movie.

On the other hand, when the sound is a little funky it’s a little frustrating. The picture can be a little funky… I don’t know why that is the rule. But for me that is the rule. If you can’t understand what they’re saying, the lo-res isn’t working in your favor sometimes. That’s not always true, because lo-fi stuff is incredibly beautiful. I love when sound is falling apart. You know, every time I make a statement of what works and what doesn’t work, I realize, that’s not true—I don’t even know why I’m saying that!

Some of the most empathetic or interesting parts of Heart of a Dog are the GoPro and iPhone footage.

We shot a lot of stuff with drones in this. I had five drones. I was using it for concerts, to have them fly around musicians and stuff. There are no laws about drones in New York City. Up and down… It’s just fantastic. You can’t do a lot of stuff, but you can do that. You can spy [with a] drone, or you can irritate people. It’s amazing. So we did a lot of that, but the footage was not very good. The cameras in front were so-so and the ones underneath the drone are very lo-res. I did use the lo-res stuff a lot, in other things that aren’t necessarily the drone shots. I used it as basis for the stuff that’s supposed to represent the phosphenes of things when you close your eyes. That’s the underbody camera on a drone looking at shadows in a big studio going up and down in colored light. In the end, the drone footage got in there in crazy ways, in the level of abstraction. But I didn’t use it for other things.

There are many shots of the West Side Highway, when the movie is talking about surveillance and you’re zooming in on a lot of cars. How did you get those?

Oh, I just went across the street from my place. A lot of that is down on the bridge by Chambers Street. It’s very local, this film. The farthest place was California. I happened to be there. It’s funny, I wasn’t gonna use a stand-in for Lolabelle, but I was in a café in San Francisco, and we were gonna go shoot some hills. And I thought, “Oh, I’ll just do some voiceover in the hills,” and there was a rat terrier at the café named Archie. I said: “Wow, I know this is a weird request, but do you think Archie could come up to the hills and do a little shooting with us?” “Yeah, sure, when?” “Well, now.” “Sure!” “Well, it might take all day.” And they said: “That’s fine.” And I said: “Well, we might even be shooting tomorrow.” “Good!” I was like, oh my God. People in California have time on their hands! And it was great. They were just so loose. So Archie is a stand-in for Lolabelle because he happened to be at a cafe.

And he was laid back?

He was super California laid back.