Interview: Julie Dash

It’s been 25 years since the theatrical release of Julie Dash’s Daughters of the Dust, which had a week-long run at Film Forum in 1991. Dash’s groundbreaking film follows the Peazant family in the early 20th century, as the younger generation is about to leave their Gullah-Geechee community off the coast of South Carolina and head up north and onto the mainland. Seeking to take advantage of “civilized” society and opportunity, they prepare to leave behind their matriarch, Nana Peazant, who holds fiercely onto her roots and insists that her children and grandchildren do the same.

Daughters of the Dust was originally met with confusion about its portrayal of a part of African American history that was, up to that point, unrecognized in the mainstream. The film’s focus lies firmly on the lives of the Peazant women, interweaving narratives of the past, present, and future and using two narrators (Nana and “the Unborn Child”). Its images are as immersive as they are elusive, with bodies always carefully situated in relation to each other as generations intermingle, conflict, and ultimately make their peace. Tableaux of the Peazant women show them as they dance, eat, argue, dream, grieve, and reminisce.

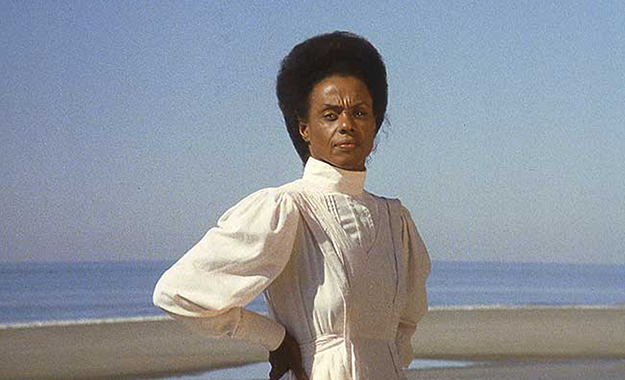

The entire film takes place outdoors, in the woods and on the beach, as black history from West Africa to South Carolina is relived through its physical marks on the present. Cinematographer Arthur Jafa brings out both the boldness and softness of blues and browns, and the dulled whites of turn-of-the-century Victorian dress, worn down by their constant exposure to nature. In this way, the keen attention given to composition, framing, texture, and hue is crucial as Daughters conceives of new symbols for black American struggle and resilience. For example, rather than whip marks, indigo-stained hands are the scars of slavery. Indelibility—physical, filial, and historical—rings throughout an unforgettable film that imagines blackness in America as legacy rather than as a story of destruction.

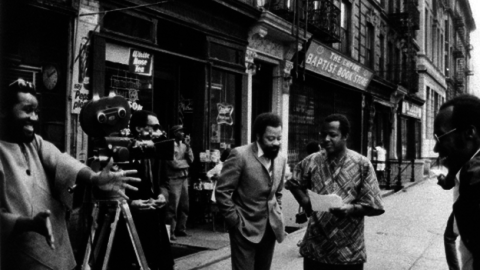

Daughters of the Dust was the first feature film by an African American woman to have a theatrical release, and has since been widely written about by academics, critics, and filmmakers. FILM COMMENT spoke with Dash, who teaches at Morehouse College, about making the film, its legacy, and what the past 25 years have been like for her as a working director. Cohen Media Group and UCLA have been restoring Daughters of the Dust under the supervision of Dash and Jafa, with a re-release slated for the Wexner Center for the Arts at the Ohio State University in May and a home video release by Cohen.

Daughters of the Dust

I spoke to Chris Horak [director of the UCLA Film & Television Archive] about how the new restoration is going to change how we see the film, and bring all these new layers of the images to light.

They did a terrific job. I was stunned. I hadn’t seen the film look like that since we edited it on film. And I remember, you just get used to what it is—it wasn’t fully color-corrected because at the time it was very expensive to go to the studio and get a better print. After that, we were out of money, so we just had to go ahead and release it, but it wasn’t there yet. But now it is. And it’s like whoa, you can see the people’s faces!

I was reading the book you wrote about the making of Daughters, and in the interview with bell hooks, you talked about how men would “fly out of the theater” seeing the lives of black women portrayed.

[Laughs] They’d be in the back of the theater and come rushing up the aisles! They either needed to go to the bathroom really badly or they were just like “I’m getting out of here because where’s the men?”

And now you’re teaching cinema at Morehouse, an all-men’s college!

Well, this is two generations later—they weren’t even born yet. Plus, I don’t know how many of them have seen Daughters. They’ve seen some of my other work like Love Song [00] or The Rosa Parks Story [02]. But one of the classes I’m teaching is called Black Women Filmmakers. And we say “black women” rather than “African American women” because I’m including filmmakers from all over the African diaspora like Euzhan Palcy and Sarah Maldoror, all of our great filmmakers. And they’re all in the class saying: “I’ve never heard of her, I’ve never heard of her.” Of course you haven’t, but now you have—enjoy! Yvonne Welbon, all these people.

I’m just contracted for this year, 2015-2016. It’s a good thing because it puts me on the East Coast—I’m working on Travel Notes of a Geechee Girl, and everyone I’m working with is on the East Coast.

It’s been 25 years since Daughters came out, but press reports usually make it sound as if you haven’t been doing anything in all that time when you really have been.

They don’t mention anything but Daughters of the Dust. And the public tends to believe I haven’t done anything, and then they start making these lists, and they say, well, list the black filmmakers, and I never make that list because it always has that little caveat “working within the last 10 years.” And it’s like, oh really? That’s the way you’re going to list things? But do they know about the commercials I do? I did a couple of Coca-Cola commercials last summer. I do car commercials. I do TV. I have never stopped working. It’s just that I’m not in the public eye that way. I had a good run with being highly visible, and now it’s time for other people to be highly visible—I have no problem with that. Let me just support them, and let me just keep doing what I’m doing, because at the end of the day it’s about the work.

Daughters of the Dust

I wanted to talk to you about Daughters both in terms of the film itself, but also in terms of what it’s generated over the past several years since its release. You were inspired by novels by Toni Morrison, for example, and also by foreign films in creating a narrative structure that actually speaks to the ways that stories are told within the diaspora and not adhering to A-to-B-to-C narrative.

Right! Binary narrative. In the culture we’re not binary, we speak in rhythms and sensibilities, we’re circular. We’re agrarian, we do improvisation, and movement and dance and speech and art and design, and it’s possible to communicate in these ways through cinema too.

And you brought together so many artists to do this. In reading the book you wrote about Daughters, the entire production sounded like a truly collaborative experience, people pitching in in all these different ways. I know people talk a lot about film being a collaborative experience, but the idea seemed to be taken to heart.

It was collaborative. And back then, Arthur Jafa talked about it as a jazz band, like a jazz orchestra out there. Working with [production designer] Kerry James Marshall and [art director] Michael Kelly Williams and the costume designers—it just started flowing. It was a huge production for an independent film. We had these big warehouses where we had the costumes stored, where they were being dyed. The art department had their warehouse where Michael Kelly Williams was making the chair and he and Kerry were making the tombstones and the figureheads. It was a museum, if you will, walking through the art department.

And it started even before we got down there. With Kerry, we were pulling images as references for the indigo plantation flashback scene, and Kerry actually built those indigo dyeing mounds, all based upon what we could find or pull together or read about about how they did it in West Africa as the foundation for what was done here. I believe we were the very first ever to have indigo as a visual theme or motif that went throughout the story. I decided, instead of showing the form of enslaved people with whip marks or scars of slavery, their scars would be the permanent blue hands from working the indigo fields, and that’s how you could tell who was a former enslaved person of the elders.

Some responses to the film were incredulous that you would dare to imagine anything through a fiction narrative rather than construct a biographical or documentary-style feature.

Yeah, and I thought about [doing] that at first and then was like, well, why do I have to? It’s cheeky to say that—that of course I have to tell you what you don’t know first and then I can do it as a drama? Come on.

Daughters of the Dust

That’s why I think the film was so ahead of its time and continues to resonate. It imagines so many things instead of just trying to tell people who they were, and it was as much about the people who made it as it was about the history, which is such a difficult thing to do in your first feature—to put so much of your imagination in a history-referencing narrative without adhering to any sort of template.

It was my first feature, but I had done quite a few shorts. I had pretty much done the same thing in—well, I got hit in the head for doing Illusions [82]. At the time, people were saying “How dare you? Isn’t that just like Imitation of Life or Pinky?” and I was like, no, it’s totally different. Like, how dare I deal with the color caste when black filmmakers weren’t doing that then. Because I made that in ’82. And with Illusions, I remember being in Rennes, France, at a black film festival, and some people, black French people, got up and walked out of the screening because they weren’t getting the full translation and simply thought I was doing Pinky or Imitation of Life, a black woman ashamed of passing for white. But I was using passing for white as in, she was like a guerilla fighter. But they couldn’t grasp that because all they could think of was the 1930s or 1950s Douglas Sirk. So I’ve been creating new realities for a long long time.

Daughters had a theatrical release, so you see so many more people coming into contact with it and it had the ability to surprise them. But that was the way your career was setting up to go, because you had been making that kind of work already, pushing boundaries.

I also think independent filmmakers, black or white, at that time we were exploring new ways of telling the stories that we already knew. We were re-framing it. Hollywood had framed things a certain way—the baseline Southern historical film was Gone with the Wind. So everyone wanted to do something that was not that. It’s amazing because now I still get screenplays sent to me with that same Gone with the Wind aesthetic. And I see it on TV all the time. That’s a false notion of the antebellum South and the postwar South. It’s still false, but people are still going with it. It’s all cotton picking when cotton wasn’t the only thing—it’s indigo, it’s tobacco, it’s all kinds of things. And then there were the enslaved people who lived, for instance, in Charleston. In the city, where my people are from, they didn’t work plantations, they were craftspeople. No one really showed that type of slavery because it doesn’t depict the aesthetic frame that’s been established with Gone with the Wind with picking cotton. They’d put on their metal badge and get up in the morning and go to work making shoes in a factory, but we’re not allowed to see that. In Philadelphia they worked in mines—in the coal mines. You never see that.

Can we change up now? It’s been 60, 75 years of the same thing over and over again. And I just turn on television now and it’s that same old antebellum farce that we’re seeing with Mammy in the kitchen who’s overweight. And scholars have already come up and said that that’s not true at all. She wasn’t fat, she was the sexual toy of the master of the house—but they create that Mammy because that image becomes the beard, it’s the cover story because no one would think that the master of the house is going down every night to sleep with Mammy because she’s big and fat. That’s been disproven. But every film you see comes up with that one. I don’t want to operate within the same frames of what’s been said.

It’s this idea that white imagination is more honest or truthful or valuable than how black people imagine their own lives. And that’s why your bringing so much of the complexity of diaspora into Daughters was so important because even now black people working in film can still feel constrained in their efforts to portray unexpected elements of black life.

But those unexpected things have resonance and they are actually a visible delight, metaphorically, emotionally. It’s just like an awakening when you’re watching a film and you go, oh, okay, wow! And I think that’s why I like foreign films so much: I’m learning, I’m seeing something new. It’s the same genres and dramas that we’re familiar with, but you see them through fresh eyes, through new voices. It’s an experience. It’s the way cinema is supposed to be.

![]()

The Rosa Parks Story

But what can also happen is that when you are that new voice and you’re telling a new story, on the flip side, you’re asked to become a spokesperson for that perspective, a token, and you’re expected to do the same kind of work over and over again. Did you feel that pressure after Daughters?

Yes. That’s why I think people can’t really understand how I did Love Song, Funny Valentines [99], Incognito [99], The Rosa Parks Story. They’re all very different types of films, different genres. But they just don’t mention it because they think, she does historical dramas, she can’t do something like a Love Song, a romantic comedy, so we won’t even mention it.

It seems as if this idea of a black filmmaker having to “break out” is less about their finally making a strong film, and more about being able to push past (or even align with) the “expectations” of their audiences.

And things have not really changed that much. I saw this film on TV—you know, because it’s black history month, and there are all these black films on TV—and it’s got the same Jane Pittman ending! That movie must have come out 40 years ago, when I was in the eighth grade, The Autobiography of Miss Jane Pittman. It’s the same old thing, but you’re supposed to be happy because now it’s a digital production.

Love Song to me feels like a precursor to a wave of black romantic comedies that I think now have been getting theatrical screen time. It’s one of the films that pushed toward this idea of showing the modern lives of young black people.

A film about a group of black women who are not talking about race. Trying to get through their daily lives without trying to be Atlanta housewives.

I haven’t seen Daughters be put into conversation much with other films. It definitely stands on its own as a piece of work that’s incredibly unique, but at the same time, this idea that people hadn’t seen this type story before or were surprised by it really prevented people outside of academia from engaging with it as a film that’s in conversation with other films.

It’s funny how it plays outside of the country without people saying it’s complex or anything. There was a retrospective of it in Taiwan in 2009. It’s played in India, all across Asia, Poland, Germany, and no one ever says anything about it being slow or difficult to follow. Nothing like that. And I think, I have to return to those places with the film. It’s always been received differently outside the country because they don’t have the same expectations of, when you say “a black historical film” and people think, oh, I know the story, roll the film. And when they’re not seeing what they expect to see, then there’s some kind of resistance.

Love Song

Daughters plays with this notion of time not as a linear thing, but as something that is interwoven and overlapping—from the grandmother to the mother to the daughter to the daughter’s daughter.

I think people can see now, and people weren’t able to understand before, but it’s sci-fi, it’s a special fiction. And people said, oh, no, it’s a historical film. It’s a meditation—it’s a cinema of ideas and what-ifs and how-sos. It’s a conversation.

After Daughters, what were your ideas about moving forward, and how did you envision the next steps of your career?

I was sure I was going to be able to move right from there to make some more theatrical films. I wrote, I had a ton of screenplays and ideas, and I was taking meetings everywhere. And that’s when I hit that glass ceiling. Bang! I went to ICM first, and then I went to CAA, and they kept throwing stories to me about the Klu Klux Klan. They had a stack of old screenplays and they were just sending them. And that’s just not what I was trying to make films about, and I would tell them about the African American women who served overseas during World War II or the Colored Conjurers, about a family of magicians—and they said, “Oh, musicians?” and I said, “No, magicians.” “Oh, I’ve never heard of that.” And if they’d never heard of that, they’d shut down. They weren’t interested in the women who were the black soldiers who served overseas, they weren’t interested in my story Digital Diva, about a black woman who was an encryption specialist. All the studios kept telling me no, but now you have all these encryption stories, Mr. Robot.

All of those sound like films I would have loved to see and would still love to see.

They were running it through their own filters. They were only interested in me doing their existing scripts that they had already paid for. And it wasn’t just the issue of race over the years, it was also an issue of gender. I was supposed to be a black woman filmmaker and I was supposed to make the films they wanted me to make. And they couldn’t see anything beyond that.

Daughters of the Dust

That’s also one thing bell hooks really hit on in that conversation. You say earlier in the book, “I realized early on that even a lot of my own people sometimes would be against me”—this idea that it was white men, then white women, then black men, and after all of that…

I even spoke to a lot of black women film executives and they had a lot of the same reactions as white men because their jobs were to be white men. So that’s why I realized it’s not just race, it’s bigger than that—it’s race and gender. And the systemic racism—those black women executives have to hold a line so that they can keep their positions. It was interesting to learn and I’m glad that there’s now movement forward with Ava [DuVernay], with Dee [Rees], and with Gina Prince-Bythewood—that they’re able to make films and have more traction.

So how did you move forward from that?

It hasn’t stopped me from working in the independent sector. I was working for Disney, Imagineering, designing multimedia pavilions. I worked for the National Underground Railroad Freedom Center museum making a $1.5 million film that plays there continually. I’m still writing and I’m still making films. I’ve never stopped. That’s the thing that some people don’t understand. They think that if you don’t get a Hollywood film you just stop in your tracks and become a nurse. I’m a filmmaker, I was a filmmaker long before those people were in the studios, probably, and I think it’s a little bit too late to turn and run now. This is what I do: I make a film, and if I can’t make a film, I teach, or I teach while I make it. I will always be a writer. Filmmaking is filmmaking. I tell stories, I like to take an idea and turn it into something visual that’s compelling, exciting, meaningful. And that’s the task at hand no matter whether it’s a five-minute-30-second commercial spot or a feature film. That’s what I enjoy doing and that’s what I have been doing.