Film of the Week: One Sings, the Other Doesn't

Happy Birthday, Agnès Varda, who turned 90 this week. Her capacity for adventure, curiosity and self-reinvention continues undimmed—as witness last year’s Faces Places, a travelogue film of encounters with French working people and their environments, made in collaboration with an artist from another generation, photographer JR. Although she has never stopped being active in both fiction and documentary spheres, Varda’s latter-day renaissance began, for all intents and purposes, with her 2000 docu-essay The Gleaners and I. This was a sort of manifesto film in which she explored the culture of artistic and ecological gleaning, or recycling, and proposed herself as a “gleaner” of images, thanks to her discovery of the new portable DV technologies then becoming widely available. She also launched a successful new career as a video and installation artist—her 2006 show at Paris’s Fondation Cartier, inspired by her holiday retreat on the island of Noirmoutier, remains one of the most memorable and enjoyable shows of its kind that I’ve seen. And Varda began to delight in promoting her own eccentric persona, in her autobiographical film The Beaches of Agnès (2008) playing a larger-than-life character with a cartoon alter ego; she turned up at this year’s Oscar nominees lunch in the form of a cardboard cutout, and can be seen in The Beaches attending an art fair dressed as a potato.

Varda has always had a sense of fun, which has often served her well in getting her serious points across. The performance-art/roadshow aspect of Faces Places comes to mind when looking at the wanderings of Pauline, aka. Pomme (Valérie Mairesse), one of the two heroines of Varda’s newly restored and re-released One Sings, the Other Doesn’t (1977). Throughout the film, Pomme—the one who sings—tours France as part of consciousness-raising feminist performance group Orchidée (meaning Orchid), singing folk numbers with lyrics written by Varda herself. In scenes that bring the film a quasi-documentary dimension, Orchidée are seen playing in various theatres and village squares, to usually small, mixed, sometimes delighted, sometimes manifestly bewildered provincial audiences. To 21st-century ears, the songs sound uncomfortably twee and on-the-nose. “I am woman . . . Not goddess, not demoness, not weakness,” sings Pomme (the rhymes work better in French); at its best, Orchidée’s music achieves a Swingle Singers sweetness that is a little too saccharine today, even if you have a very retro ear. But what counts is the intention and the insistence of the delivery; Pomme and her band may seem to be pushing a hard agitprop line, but we see them doing their stuff, apparently for real, and their message needed to be conveyed in France in 1977, where it still represented a radical proposition.

Varda described One Sings, the Other Doesn’t as a musical, although it’s much less convincing in those terms than her 1962 feature Cléo from 5 to 7, which featured the heroine singing to piano accompaniment from Michel Legrand. One Sings, the Other Doesn’t really feels more like a chronicle, a novelistic mini-saga that follows two women living their lives in parallel but sometimes coming together, from 1962 to an epilogue set 14 years later. When the film starts, in 1962 (Varda, working on a restricted budget, pointedly refuses to offer a literal reconstruction of the period’s look), Pauline is a teenager, first seen wandering into an art gallery run by photographer Jérôme (Robert Dadies), who has mounted an exhibition of his portraits of women. Pauline gives the show an appraising once-over, then asks why these austerely depicted women, some with children, all look so glum. Varda’s film has its dark moments, but overall offers itself as a militant refusal of glumness. It is intensely optimistic, even utopian—a word that the film periodically uses unashamedly, indeed with pride.

Jérôme’s partner is a former neighbor of Pauline, named Suzanne (Thérèse Liotard). Already a mother, she’s pregnant again and feeling neglected by the moody Jérôme—who indeed soon departs the household by hanging himself. Varda doesn’t make it clear how well Pauline already knows Suzanne, but right from the start, she’s moved by empathy and the prerogative of female solidarity to help Suzanne get an abortion—illegal in France at the time—by tricking her highly traditional parents into giving her money. This gesture cements the pair’s friendship, and comes to define both women’s roles in society over the next decade—making her way in the world as a single mother, Suzanne runs a family planning center, while Pauline, soon renamed Pomme, becomes an activist and consciousness raiser.

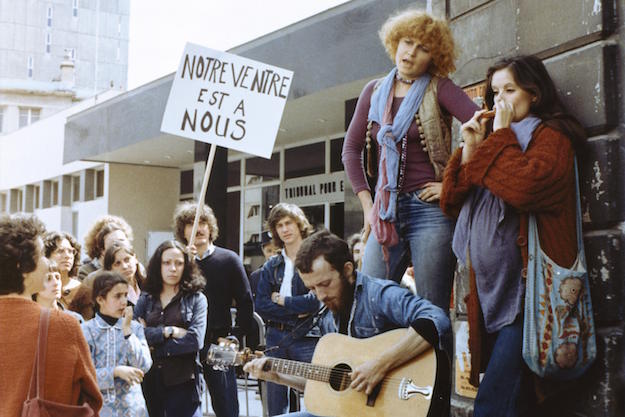

The action jumps to 1972, and an abortion rights demonstration in Paris. This episode is central to the film’s rootedness in real-life struggles. Varda herself was one of the signatories of 1971’s “Manifesto of the 343,” published in the left-wing magazine Le Nouvel Observateur and signed by women who had themselves had abortions. They included actors (Jeanne Moreau, Catherine Deneuve, Delphine Seyrig), writers (Françoise Sagan, Monique Wittig, Marguerite Duras), and other cultural figures (theatre director Ariane Mnouchkine, singer Brigitte Fontaine, designer Sonia Rykiel). Another was the lawyer Gisèle Halimi, who founded the feminist group Choisir (To Choose) to protect the signatories, and who appears as herself in One Sings, the Other Doesn’t, intervening with police at the demo. This context makes it clear what kind of film this is: not just a work of fiction set against a contemporary background, but an active engagement with that background. Some of the documentary moments are when One Sings, the Other Doesn’t most comes alive: for example in the faces of women waiting for abortions in Amsterdam, or the apparently real spontaneous intervention by a woman who objects that Pomme’s song “The Bubble Woman,” hymning the experience of pregnancy, could be taken as anti-choice propaganda.

You might call One Sings, the Other Doesn’t a women’s buddy movie or a female romance, although its terms of reference are specifically heterosexual. Its baseline is the friendship between Pomme and Suzanne, although they’re rarely together during the film: their stories alternate, as they travel through life separately but in parallel, communicating largely through postcards, intermittently narrating their lives in voiceover. They’re a yin-yang duo. Pomme is a young Paris bourgeoise, sloughing off her repressive upbringing to discover the realities of a wider world; Suzanne is from the country, and one of the film’s most memorable sequences, and arguably one of its most durably cinematic, shows her back on her parents’ austere farm, doing daily tasks under their bleakly disapproving gaze. One of Varda’s most felicitous devices is counterintuitive casting: Suzanne the paysanne is played by Liotard, whose soigné beauty would more conventionally suggest cosmopolitan sophistication, whereas Mairesse is robustly boisterous. It’s Mairesse who proves the more striking presence, with a punkish defiance beneath the Botticelli halo of ginger hair; Liotard’s Suzanne is often melancholically contemplative, but not a great performer, her moment of tearful high drama in the first act nearly scuppering the movie from the start.

Suzanne’s story is partly about the meetings she holds about contraception and child-raising, partly about her intermittent love life as an independent, but sometimes isolated woman. We only hear about an affair with a mainly absent naval officer, while her friendship-cum-romance with an amicable and feminist-friendly, but initially married, male doctor is a slow-burning theme in the film’s later sections. Varda generally seems a lot more interested in Pomme, who—being an artist—is effectively her alter ego. Pomme’s story centers around romance, then marriage, with an Iranian man, Darius (Ali Rafie), a dashing and promisingly right-on type.

Pomme accompanies Darius to Iran, on a journey that’s very much flagged up as a touristic illusion: the first shot from it, showing the couple at a beautiful historic site, is shot symmetrically to suggest one of her postcards. But returning home has brought the traditional macho out in Darius; the couple decide to raise two children apart, in their own countries, and Pomme returns home. This goes in tandem with her discovery of a real, harsher Iran, with drab vistas shot in a more unforgiving documentary style. But the Iran section proves to be the film’s blind spot. We see images of Iranian women, Pomme blending into the crowd, all wearing veils; but we learn nothing about their lives, and their presence remains merely local color. Was Varda not interested in them, or somehow unable to meet and talk with them? It seems a very strange omission, given her credentials as a cinematic traveller fascinated by other cultures (her documentary work includes portraits of Cuba and of the Black Panthers in Oakland in 1968), but this framing of the Iranian picture as strictly a French woman’s experience abroad severely limits the film’s possibilities.

Ending in 1976, the film follows its characters’ lives through to a happy present, with signs pointing to a hopeful future. A new generation is represented by Suzanne’s daughter Rosalie (played in the final section by the director’s daughter Rosalie Varda), who as a teenager tells an insistent older boyfriend that the whole “romantic walk home” scenario is the oldest cliché in the book, and that if she sleeps with him, it’ll be on her terms and in her own time.

Varda’s versatility, longevity and cheerful matriarch image have made her cinema’s most distinctive feminist role model, and the time is clearly right to rediscover different achievements of feminist history, meaning that One Sings, the Other Doesn’t couldn’t be more timely a re-release. But despite its historical importance and its relevance to contemporary debate, it hasn’t, in itself, dated well. That couldn’t be said of the vigor and stylishness of Cléo from 5 to 7, which just seems to grow in freshness, while a more confrontational statement such as Chantal Akerman’s Jeanne Dielman…, from 1975, has a rigor that’s much more attuned to today’s tastes.

The intimate dramas of One Sings, the Other Doesn’t feel less interesting than the wider social dramas they are sketched against, and while Mairesse’s own vital character emerges from the restrictions of the diagrammatic heroine that Pomme becomes, Liotard’s Suzanne rarely imposes herself with much force, coming across in her private moments as a contemplatively doleful observer of her own story. Modern viewers will also have to take the somewhat precious carnival aspect of Pomme’s shows with a pinch of salt, along with the film’s residual flower-child fuzziness in general (France’s hippie, or baba cool, culture was still deeply entrenched at this point: hard to imagine that just across the Channel, punk culture was already in full blast). When characters show up such as a soft, sensitive, flute-playing single dad, with a little son named Zorro (the director’s son Mathieu Demy), you wish the Slits’ tour bus would hove into view, blasting dub reggae and blowing the cheesecloth and satin away.

One Sings, the Other Doesn’t opens June 1 at BAMcinématek.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.