Film of the Week: A Ciambra

Italian neorealism is alive and well in the hands of writer-director Jonas Carpignano—a fairly textbook version of neorealism, at that. In his second feature A Ciambra, which lists Martin Scorsese as an executive producer, Carpignano has cast unknowns: a Roma family named Amato, who are apparently playing versions of themselves, their characters sharing their real names. The setting is the port community of Gioia Tauro in southwestern Italy, the dialogue is largely in Calabrian dialect, and the drama, as far as one can tell, seems to emerge organically from the kind of situations that Amato family members might actually find themselves in.

A Ciambra, in other words, descends in a direct line from Visconti’s La Terra Trema and, in some ways, offers few surprises: given Carpignano’s subjects and the life they lead, this is in many ways exactly the kind of film you would expect to emerge. The narrative is a coming-of-age story culminating in one character’s rite of passage in the form of a stark moral dilemma, and the outcome feels a little neat; it should be noted that Carpignano’s film, which made its debut last year in Cannes’ Directors’ Fortnight, has been through development at the Sundance Lab. Then again, having contrived, even schematic story-lines never spoiled Vittorio De Sica’s best work.

Still, the measure of the success of a film like A Ciambra isn’t necessarily that it departs from a historically successful aesthetic program; it’s perhaps more to do with the degree to which a filmmaker undertakes to become embedded in the world that’s being explored. In Carpignano’s case, that embedding seems absolute and very intense. Brought up in the U.S., Carpignano moved to Gioia Tauro to embark on a projected trilogy of features set in the town. The first was Mediterranea (2015), about the exodus from Africa of those migrants whose arrival has made Italian Mediterranean culture newly complex in ways that cinema hasn’t been able to ignore (from its being the central theme of Gianfranco Rosi’s Fire at Sea to its awkward sidebar status in Luca Guadagnino’s A Bigger Splash).

The immigrants from Mediterranea are still on the scene in A Ciambra, now eking out a harsh, precarious existence in a refugee camp; one character from that film, Ayiva from Burkina Faso, played by Koudous Seihon, again plays a major role. But this time the focus shifts to another marginal community, with its own history of severance from its roots. Those roots are hinted at in the film’s opening images: a young man in a hat, gazing at a horse on a hillside. We’re in the past, in the youth of Roma patriarch Emiliano: a glimpse which serves to remind us how far the Amatos have come from the old nomadic traditions. Today the family lives claustrophobically on the edge of Gioia, in a run-down community—Carpignano has referred to it as a favela—called A Ciambra. There, father Rocco runs a chop shop, dismantling stolen cars for the local Calabrian hoods (referred to simply as “the Italians”) to whom the Amatos are reluctantly in thrall.

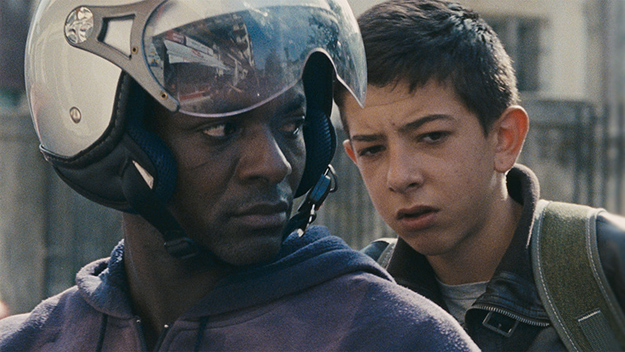

The clan is large and sprawling, and initially it’s hard to work out who belongs to which generation: 14-year-old Pio (Pio Amato, previously seen in Mediterranea) appears to have several younger siblings, although some turn out to be his nephews and nieces, while pugnacious matriarch Iolanda (Iolanda Amato), who looks as if she might be Pio’s grandmother, is in fact his mother. Oh, and Pio’s older brother Cosimo is played by Damiano Amato: there is in fact a Cosimo Amato, who played his own part in a 2014 Carpignano short, also called A Ciambra, but his twin Damiano plays the part here.

At any rate, we get to unpack the relationships at our leisure. The film makes us the feel the way we do when we spend time with a large family we don’t know; we gradually figure out who’s who as we listen to the children throw taunts at each other (“I’m gonna piss in your mouth,” a pre-teen tyke sneers at his older sister), or just take in everyone’s rapport over long, chaotic dinner scenes. These have the same kind of free-flowing intimacy and comfortable agitation we saw in Abdellatif Kechiche’s Couscous—only more so, because in this case, these people have actually been dining together their entire lives.

At the center of this permanent family hurricane is Pio; he sets the pace for the film’s energy, with Tim Curtin’s camera tending to pelt after him at the kid’s own breakneck speed. At the start of the film, it’s clear that hanging out with his juniors is beginning to cramp Pio’s style: raging with impatience, he takes off after Cosimo, keen to make a short cut to manhood and to get in on the business of his elders. At a club where Pio hangs out with Ayiva, it’s clear that manhood will at some point involve women. There’s a girl that Pio is shyly keen on, but the older males want him to do things the approved ritual way, putting him on the dance floor with a young woman of their choice. Pio’s nervous grins make it clear he’s not ready for that stage of initiation yet; young Amato’s candor couldn’t be more transparently affecting in this scene.

A more direct and perilous path to male graduation begins when “the Italians” drop by at the house, treated by the family with the wary respect due to dangerous overlords. The Italians are angry, and go into conference with Cosimo and Rocco about a car theft that wasn’t authorized; there’s work to do to make up for this, and Pio, who’s spying, wants in. Before long, he not only finds work but shows he has initiative to spare (what’s the Calabrian for chutzpah?): when the carabinieri show up, he steals their car, and when entrusted with returning a stolen Fiat to its owner, for a price, he arranges himself a handsome commission.

Pio seems set on a path to local glory. In one scene, he delivers a TV to a gathering of Africans so that they can watch a football match. He becomes the toast of the evening, fussed over by a young African woman—the film is good on Gioia’s different communities: the crowd is mainly Ghanaian, but the woman points out that she’s Nigerian, and so an outsider, while Ayiva is very much attached to his homeland, Burkina Faso.

As in so many family dramas, especially when there’s crime involved, it’s an outsider who gives the best advice, and with whom Pio forms one of his closest bonds: surrogate big brother Ayiva, who lives outside the law but knows it’s wisest not to step too far beyond it. He doesn’t want to go to jail or back to Burkina Faso, and counsels Pio to watch his step. Of course, the kid does anything but. He shows his ability to hold the fort when both his brother and father get arrested, but ends up committing one of those crazy acts of youthful hubris that invariably trigger calamity in stories like these (see another recent Calabrian drama, Francesco Munzi’s 2014 Black Hearts). There’s a chance of redemption, but it inevitably means an act of betrayal. And that, the film ruefully concludes, is what adulthood so often proves to be about.

A Ciambra is a film of ferocious energy and observational keenness that, despite eventually smacking of over-contrivance, feels as if it’s genuinely letting the characters and their energy dictate the pace and the direction of things. Some lovely contradictions emerge in Pio’s character, possibly a reflection of his real-life nature. He’s terrified of lifts, and has a phobia about the speed of the trains he steals luggage on, which makes him reluctant to ride them, yet he seems more than comfortable on the back of a speeding motorbike. The film also brings us close to its characters, even makes us love them, while at the same time we’re shocked by the degree of racism that they show—which, of course, as Roma, they’re themselves subject to.

On the minus side, while the film doesn’t necessarily feel over-long at 118 minutes, it does sometimes lack shape. The course of events feels baggy and repetitive—we keep going back to the club and to the train—and you wish things had been tightened up a bit, with perhaps a little less incident, to give the family itself room to breathe a little more. It would have been good to see something more of father Rocco, who takes a bit of a backseat, and a lot more of the formidable Iolanda, who seizes the camera’s attention and grips onto it with indomitable ferocity. The one really awkward touch is the use of grandfather Emiliano to show how the Roma life has changed: the glimpse of his past, and a photo of his young self on the wall, are quite enough, but we could have done without his portentous declaration, “Once we were always on the road . . . We answered to no one . . . Remember, it’s us against the world.” Pio doesn’t need to be told that, and I’m not sure that we needed to see a hallucinatory invocation of that past, involving a wall of flame and a ghostly horse wandering free.

As usual, when an outsider decides to offer a fictionalized depiction of the lives of real people, there’s an ethical question at stake—especially when the subjects are economically disadvantaged or socially marginalized, and even more so when their existence is involved with criminality. A filmmaker may undertake to represent a community, or a portion thereof, but we may always question whether the subjects want, or need, or benefit from being represented in the first place. With films like A Ciambra, the outcome may be that some people who rarely leave their place of origin might find themselves standing on a festival red carpet or two for a brief heady period, but there’s no way of knowing what effect that will have on their lives. Some, including notable Ken Loach discoveries, have become professional actors; others, notably Fernando Ramos da Silva, the lead in Hector Babenco’s Pixote, find their on-screen selves, and the disrepute that often attaches to them, very hard to throw off.

Judging from interviews, Carpignano seems well aware of the dangers, and what’s striking is that, while they’re enacting a story of criminal life, the Amatos don’t seem remotely self-conscious. Pio Amato is entirely unlike the young Neapolitan characters of Matteo Garrone’s considerably more stylized crime story Gomorrah, who are acutely and awkwardly aware of playing at gangster roles in the style of Scarface’s Tony Montana; there’s certainly none of the grotesquerie of Gomorrah here. Pio the movie character doesn’t seem to want to be anyone except Pio Amato, and that’s a role that the real-life Pio shows he’s supremely, and with a magnificent lack of self-consciousness, qualified to play.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.