Film of the Week: Bohemian Rhapsody

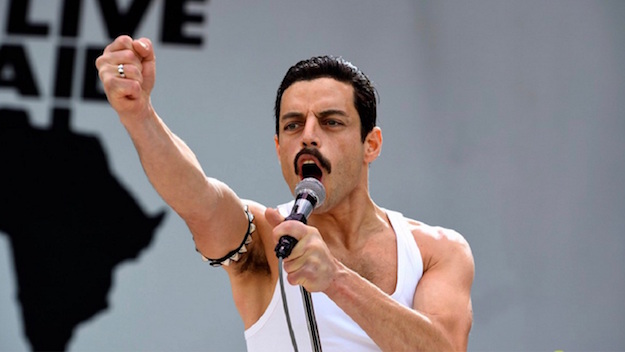

There are two magnificent flourishes in Bohemian Rhapsody, the long-awaited Queen biopic. One is the playful transformation of the familiar opening 20th Century Fox fanfare, brass replaced by the band’s trademark sound of gnarly guitars and choral falsettos. The other is the entirety of Rami Malek’s performance as the band’s singer Freddie Mercury—pretty much the only reason to see the film. As for the rest… mamma mia, mamma mia!

Once referring to a specific Eastern European kingdom, the word “bohemian” came to refer to anyone who had an artistic, marginal lifestyle, and was regarded by those to whom it was applied as a badge of honor. By the 1970s in Britain, however, when this film begins, the word was thoroughly debased, and effectively denoted anyone who occasionally ate salads or wore a velvet jacket at weekends—and that’s pretty much the flaccid sense of the word that comes to mind when watching the film.

A troubled production, with Sacha Baron Cohen leaving early on, Bohemian Rhapsody is scripted by Anthony McCarten, with the direction credit going to Bryan Singer—although he too left the project mid-shoot, with Dexter Fletcher stepping into the breach. You could say that the film’s lukewarm quality is true to the band itself: Queen come to mind as bohemian only in a very adulterated sense, in that superficially the band had all the trappings of glam rock’s sexual ambivalence, yet came to embody the “classic rock” tradition at its most macho and heterosexual. Born Farrokh Bulsara, the son of Parsi immigrants from Zanzibar, Mercury invented himself wholesale out of a British tradition of West End theatricality, raffish music-hall comedy, and hippie preciousness, creating a persona that started off as a flouncy frills-and-scarves flamboyance, later switching to a cartoon version of sex-club queerness.

Yet you rarely hear of gay fans claiming that they were liberated by his persona in the way that so many were in the ’70s by Bowie, Lou Reed, and others. Mercury’s camp performance style and lyrical repertoire were really homeopathic in the context of the band: a little dose of harmless pantomime fun that leavened the galumphing heaviness of what became one of the ultimate blokes’ bands, and corporate dinosaurs, in 20th-century pop. There’s a fascinating story to be told about how Mercury’s identity, both as an Asian immigrant and a gay man, was subsumed by the normative mainstream of British culture. And to its credit, the film does more or less attempt this—but it does so wearing hob-nailed workboots, rather than the satin slippers required by such a delicate dance.

The film opens in 1985, with Freddie in his luxury home, draped in a silk dressing gown, alone but for his cats and a print of Marlene Dietrich—establishing a theme of the lonely, doomed gay man, which the film milks persistently as if it had actually been made in 1971 or thereabouts. We then flash back to 1970, with Bulsara seen working as a baggage handler at Heathrow and at home with his worried, highly traditional parents, telling them, “It’s Freddie now.” His dad ruefully shakes his head—“You can’t get anywhere pretending to be someone you’re not”—showing a fundamental misunderstanding of showbiz.

Freddie goes off to a gig by a band named Smile, who are temporarily on the skids, as their singer is leaving to join a band with better prospects, called Humpy Bong (believe it or not, this is actually true). Freddie offers to step into the breach, but the band members don’t think he has what it takes to be a singer because of those extraordinary teeth—although he explains that his four extra incisors increase his range. Then he blasts them with an impromptu demonstration. He baffles these stolid hippie lads with his new name for the band—“As in Royal Highness—and because it’s outrageous”—and the rest is history.

The actual story of Queen’s progress and development as outré and wildly versatile hit-makers is rather laboriously charted—not least because of the production involvement by other band members and their manager Jim Beach. There are some delightfully leaden “inspiration” moments—as when Freddie idly plays the familiar piano intro to “Bohemian Rhapsody,” and says he’ll get round to using it in a song one day. The recording of “Rhapsody” itself, in joyless rural environs, is an amusing romp, with drummer Roger Taylor (Ben Hardy) cheerfully hitting the high notes on the chorus (did he really say, “Who even is Galileo anyway?” I mean, even by the standards of jokes about rock drummers…). There’s much larking around with that familiar folk demon of music bios, the blinkered record company executive who just can’t see the brilliance. He’s played here, in fake stubble and a Hawaiian shirt, by none other than Mike Myers, a nice bit of novelty casting for the generation who discovered “Rhapsody” through the joyous in-car karaoke of Wayne’s World. Sure enough, the man from EMI proves wrong—as do those joyless fiends the critics, to whom the film sends a bit of a screw-you by plastering the screen with quotes from historic bad reviews of the record. Cut to a concert crowd ecstatic at the song—because the people understand!

Alongside the career stuff, which is done in serviceable comic strip style, the film attempts a rather earnest psychological portrait of Mercury himself, centered on his troubled love life and what is presented here as an agonizingly closeted sexuality. Early on, he meets Mary Austin (Lucy Boynton) after an exchange of flirtatious looks, then visits her at the clothes shop where she works—Biba, a place where in the early ’70s, many a London boy went to experiment with being a bit more female (the New York Dolls famously did a gig there in 1973). She puts a scarf and eye-liner on him—“You have such an exotic look . . . I think we should all take more risks.” They move in together, and are absolute soul mates—but why does Freddie feel so… strange… while gazing at a passing trucker on a U.S. tour?

Soon after, Freddie is nervous when made a pass at by Paul Prenter (Allen Leech), who’s part of his management team—shown as a thoroughly bad influence who encourages him to go solo, then whisks him off to seclusion in Frankfurt, where his house is quickly filled with bad company—a very out gay circle, or “these people” as Mary puts it, before she saves Freddie from himself. Prenter is that hoary stereotype, the predatory gay man, as well as a Machiavellian evil genius and a betrayer, who goes on TV to spill the beans on Freddie’s “countless lovers” and “wild, drug-fuelled sex parties.”

Gay Freddie may be, but it’s clear that Mary’s the one that he’s always loved—the faithful girl at home with the sofa and cats, a quite colorless figure here. There’s an extraordinary coming out scene which has the ring of a ’70s daytime soap. If the film were directed with any grace, you could almost believe it was aiming for knowing laughs, with a wink to lovers of the Mommie Dearest school of biopic: “Freddie, what’s wrong?” worries Mary. “Something’s been wrong for a while now.” Subsequently, the lonely Freddie (“You’ve got children, wives—what have I got?”) is never shown as remotely comfortable with a gay identity or lifestyle—or ever as actually having, let alone enjoying, any of those “countless lovers.” He’s even given a pious little lesson in self-respect by a waiter at a party—a supposedly wild bash that the other members leave in embarrassment, but that’s as outré as a Halloween tea dance at the vicarage. The waiter, Jim Hutton, resists a pass Freddie makes, but will eventually become his partner: “I like you too, Freddie. Come and find me when you decide you like yourself.”

While Freddie walks alone in life, on stage his greatness is seen as the ability to unite multitudes—and this film certainly celebrates the audience as a roaring crowd, almost in militant opposition to the idea of the individual. The scene in which guitarist Brian May (Gwilym Lee) devises the bullish thump of “We Will Rock You” is especially horrifying—he imagines thousands of people stomping along in unison, which suggests a grimly totalitarian image of stadium rock. The film suggests that Queen’s ultimate achievement can be summed up by swooping shots of CGI-generated thousands at the Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium in 1985. There’s a nastier political edge to the film: a scene in which journalists at a press conference quiz Freddie on his sexuality, their icy, cruel faces shown in extreme close-up through distorting lenses. True, the British tabloid papers have always been notoriously feral, but now is not a time in history when it’s wise or helpful to perpetuate the image of the press as a seething mass of satanic malefactors.

The film’s final act is a melancholy aria, as Freddie faces the reality of AIDS-related illness (he died in 1991, aged 45). There’s one brief, sweet sentimental moment to suggest his solidarity with a community—a gentle exchange of his trademark “Ay-oh!” with an ill boy in a hospital corridor. Bohemian Rhapsody ends ludicrously as Freddie has a reconciliatory meeting with his family before telling them he’s off to Live Aid: “We’re all doing our bit for the starving children of Africa.” In this moment of apotheosis, he declares, “I’m going to be what I was born to be—a performer, who gives the people what they want.” Which is great—unless you’re more inclined to admire those artists who give the people what they don’t yet know they want, something that the inventive Mercury was actually rather good at.

What saves the film throughout is Rami Malek’s performance, which is at once sweetly earnest and knowing in its magnificent, self-mocking ludicrousness—a mesmerizing evocation of a man for whom self-mocking ludicrousness was his absolute forte. McCarten writes some highly juicy repartee for Malek to savor through those exaggerated incisors—“My throat feels like a vulture’s crotch,” “Get out, you treacherous pissflap.” Shorter than Mercury, and with the big eyes of a child in an adult’s body, Malek plays Mercury as a man who’s not so much drunk on life as enjoyably, saucily tipsy on it, and a little star-struck with himself. The throaty mock-posh voice is wonderfully ripe too, suggestive of permanent epicure relish, as though Malek were forever chomping a big chunk of richly scented Turkish delight. His ripeness is of course accentuated by having the rest of the band played (unfairly? who knows?) as ponderous suburban dullards, but the swagger pays off even at such clunky moments as when Mary says, “You’re burning the candle at both ends,” and Freddie replies, “Yes, but the glow is so divine!” Overall, apart from a few larky comic moments, the glow in the film is entirely Malek’s.

It’s hard to imagine that Dexter Fletcher—who, after all, got his start in film acting for Derek Jarman—could be partly responsible for so thoroughly a de-queering of a showbiz legend. Bohemian Rhapsody proceeds as if Velvet Goldmine never happened (or even punk, for that matter). It’s not unenjoyable as somewhat sitcom-like entertainment, but it takes a very complex, troubled life and flattens it out cartoonishly—and whether you care for Freddie Mercury’s music or not, it does him a terrible disservice. This is not the biopic he deserved—spare him his life from this mon-strosity!

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.