Film of the Week: Santiago, Italia

Images from Santiago, Italia (Nanni Moretti, 2019)

One thing we learn from his new documentary Santiago, Italia is that Nanni Moretti is not a bad interviewer, and that he’s also modest. This comes as a surprise because the Italian filmmaker and actor has long been renowned as one of the foremost comic narcissists of contemporary cinema, pursuing his wry self-portraiture from the mid-’70s on, most famously in his ’90s breakthrough films Caro Diario and April. Given his patented persona—a cantankerous, disillusioned left-wing cinephile—it seemed unlikely that Moretti would keep himself out of a documentary about Italy’s relation to the advent of the Pinochet dictatorship in Chile, and yet he does. We hear his off-screen questions only sporadically during the film, but when we do, they’re concise, relevant, and scrupulously impersonal: a stark contrast with, say, Werner Herzog’s fawning and uninformative questioning of Mikhail Gorbachev in his recent portrait of the world leader. In fact, we only see Moretti on camera once during the film, an appearance entirely germane to what he’s setting out to show.

Equally, Santiago, Italia—now streaming in Film at Lincoln Center’s Virtual Cinema program—suggests that Moretti is not the most inspired documentarist, although his 2003 documentary short The Last Customer was much praised. But then the new film doesn’t set out to be ground-breaking or stylistically distinctive. It’s a straight talking-heads account of the overthrow of the Allende government and the military coup of September 1973, as told by those whose lives were permanently changed by it. In particular, the film is about those—some 250 of them, according to accounts, adults, and children—who found shelter in the Italian embassy in Chile’s capital Santiago, before moving to Italy as refugees.

However, the film takes a while getting to this. For its first 45 minutes or so, Moretti covers the background to this story. The film begins with the election in 1970 of Socialist president Salvador Allende, seen in archive footage alongside eminent supporters like poet Pablo Neruda. Among a host of interviewees who lived through the period, the best-known to cinephiles will be the filmmakers Miguel Littín (The Jackal of Nahueltoro, Alsino and the Condor) and Patricio Guzmán, whose own career has been dedicated to documenting Chilean history since the ’70s. Littín and Guzmán recall the euphoria that attended Allende’s triumph, and the genuine sense that his government would be able to fulfill its vision of overcoming poverty. The story of what happened next is only too familiar, and disheartening: a hostile response from the right-wing press, which systematically promoted the idea of mismanagement on the part of Allende’s government; U.S. support for Allende’s opponents; market manipulation from the right resulting in consumer goods becoming inaccessible; and so forth. The most painful moment in this section of the film is of Allende declaring, “I have no vocation to be a martyr”—which is precisely what he became.

The emblematic nightmare image of the coup comes in footage of the national air force bombing Santiago’s presidential palace La Moneda; one woman, then aged 7, remembers the planes flying especially low over the city, and you can well imagine this memory haunting her nightmares ever since. Littín remembers hearing of Allende’s death (unlike some, he is convinced that the deposed president was murdered, rather than killing himself) and recalls a soldier, when the news was announced, taking off his helmet and saying, “Shit, what are we doing?” An Italian diplomat remembers visiting the football stadium where masses of Chilean citizens were forcibly interned, and feeling he had suddenly wandered into “a B-movie with Nazis.”

All this is familiar, not least from Guzman’s own films: his imprisonment in the stadium was touched on in his recent essay film The Cordillera of Dreams. Things get more revealing when Moretti talks to people on the other side, like military man Guillermo Garín, a former close associate of Pinochet. Garín insists that the coup was a good and necessary thing, because Allende’s system would have led to totalitarianism: “We were the true defenders of democracy.” Moretti, off-screen, coolly questions Garín, but you sense an edge of irascible disbelief in his voice.

The denial by Pinochet loyalists becomes even more disturbing in an interview with Raúl Eduardo Iturriaga, currently in prison for his actions; although not identified on screen as such, he is an army general and former deputy director of the Chilean secret police, the DINA. Iturriaga reels out a string of clichés, grimly echoing other historical atrocities: “The army are professional people who followed orders,” he says. What he and his peers did, he insists, they did in the correct manner, to people who had been duly condemned by court martial—although yes, he concedes, “There were some cases handled in an irregular manner.” Besides, “people on the other side also killed people.” And besides, a lot more such cases happened in Argentina. The sequence ends with a shot of Moretti and his interviewee standing face to face, the only time the director is seen in the film. Iturriaga tells Moretti that the reason he agreed to appear in the film was because he had been told by a third party that it would be impartial. There’s the briefest pause, then Moretti replies, “I’m not impartial.”

As for the victims of people like Iturriaga, there’s a devastating sequence that begins when artist Victoria Sáez, whose own name was given to authorities by a comrade under torture, says that she personally cannot blame those people who were induced to speak because she doesn’t believe that anyone can resist torture. However, a journalist named Marcia Scantlebury did resist. Locked in the secret police’s Villa Grimaldi for 45 days, she says that she and her peers will openly talk about what happened to them, because it’s a way of exorcising the horror. She contributes a devastating touch of abyss-black humor, recalling the adhesive tapes over prisoners’ eyes, which ripped out their eyelashes when torn off. “They’ll kill us,” Scantlebury remembers saying, “but I want to die with my eyelashes.”

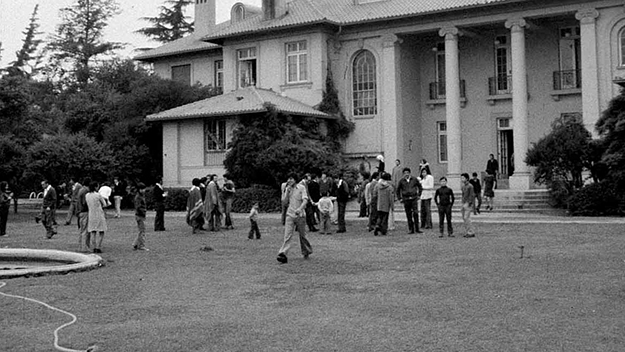

The film’s original insights start coming around 45 minutes in—that is, just over halfway—as we learn about the Italian embassy, then the only one in Santiago still open and accepting refugees. You got in over the wall, which was slightly lower in one place; one man remembers getting into practice to climb over, and wishing that he had listened to the schoolteacher who told him that gymnastic skills would one day come in useful. We hear stories from people who made it over the wall and were surprised to find a swimming pool in the garden, and people sunbathing around it; or who found safety and comfort sleeping in one of the Embassy’s luxurious bathtubs. Alonso Sotomayor remembers being one of 30 or 40 children there, whose daily game was “cops and robbers” adapted into “cops and refugees.” There was comedy: one woman, recalling how “we were pure Stalinists,” remembers a man being expelled from his particular party for refusing to peel potatoes. But there was also horror: at one point, the dead body of a young woman named Luni, a member of the MIR (Revolutionary Left Party), was thrown over the wall as a scare tactic by police, who spread the claim that she had been killed in an orgy; we see a grim archive clip documenting this episode.

Moretti’s film is a testament to the moral decency of the Italian embassy in welcoming all these refugees, but it doesn’t glorify his nation’s government at the time. An embassy official says that people were fleeing Pinochet’s Chile “like people flee Africa now”; but similarly making a bleak connection with our own era, diplomat Enrico Calamai notes that Italy’s foreign ministry then was reluctant to grant visas to asylum seekers, because it was worried about what is known today as the “pull factor”: in other words, that others might be encouraged.

Chileans did make it to Italy, though, as seen in the film’s final chapter, and their memories could not be more positive—or more of a reproach to Italy now. People recall getting work in industry and agriculture, thanks to solidarity from a welcoming socialist society: the region of Emilia Romagna called itself “Red Emilia” and declared, “Emilia Rossa has work for Chileans.” One woman says that Chile had treated her “like a wicked stepfather,” Italy “like a mother.”

Another woman got a specialized post training people to work with disabled children, and remembers, “Never once did an Italian say, ‘Why her? She’s a foreigner.’” The implication is that that would never happen today. We have become used to a world in which governments bridle at the prospect of extending refuge to immigrants in need: Italy’s role in this world picture has been a consistent theme of its national cinema for years now. “I’d arrived in a country that resembled Allende’s dream,” recalls one refugee. “[Today] it increasingly resembles the worst aspects of Chile.”

At its best, Santiago, Italia is lucid and informative, although it takes its time getting into gear, suggesting perhaps that Moretti didn’t have enough material covering the embassy or the migration, and was therefore obliged to cover familiar ground in the lead-up. He could presumably have gleaned more information about the heightened conditions of life in in the embassy, and—whether or not more archive footage was available—have contrived to bring this specially intense period more fully alive through varied and detailed testimony. And he could have done more to examine questions of life and identity raised by those Chileans who became Italian after they emigrated. The film ends with a rousing performance by brass band Banda la Marimorena, representing a younger generation of Chilean-Italians. It leaves you on a high note, and somewhat intensely frustrated at the thought of what this film could have been. Still, Santiago, Italia is not a Nanni Moretti Film in the upper-case sense, and it didn’t need to be, and you can’t help being glad that it wasn’t.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes the Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.