Film of the Week: Lords of Chaos

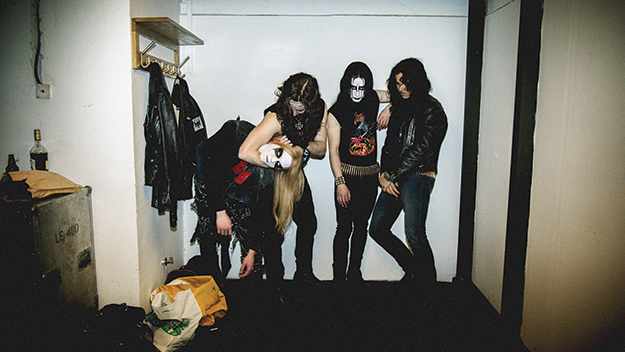

The young men of Lords of Chaos have faces white as funeral ash, clothes black, black as the abyss; they also sometimes wear stonewashed denim and sturdy Nordic jumpers. These are the denizens of the black metal scene, kids from nice Norwegian middle-class homes who dedicate themselves to a singularly gloomy form of reaction against suburban conformity. It’s the old story of bourgeois rock ’n’ roll revolt, but with a singularly bleak edge. In this story, it’s all preposterous, it’s all posing—until they prove they mean it.

Based on the nonfiction book by Michael Moynihan and Didrik Søderlind, Lords of Chaos traces certain notorious events in the Norwegian black metal scene in the late ’80s and early ’90s. It’s co-scripted (with Dennis Magnusson) and directed by Jonas Åkerlund, who brings an insider familiarity to the story; he started out as drummer in Swedish black metal band Bathory, before becoming a video director for such stygian deathgods as the Scissor Sisters, Madonna, and Roxette. As a filmmaker, Åkerlund is best known for 2002’s manic Spun, while his latest film is Mads Mikkelsen thriller Polar, now on Netflix. The English-language, largely American-cast Lords of Chaos is perhaps best described as true-crime horror farce: it’s a chronicle of murder, suicide, madness and music scene machismo at its worst, and it starts with the caption, “Based on truth… lies and what actually happened” (these days, we seem to be getting a lot of these facetious get-out clauses for films with a somewhat freewheeling attitude to poetic license).

The film is narrated by one Øystein Aarseth (Rory Culkin), a young Norwegian guitarist who in the ’80s reinvented himself as Euronymous, mainstay of a black metal band named Mayhem. There’s much humor from the start about the clash between Euronymous’s satanic persona and the mundane reality. “We are Mayhem!” he declaims at a band rehearsal, in a pit-of-hell (pit-of-the-stomach) roar; his preteen sister, bopping in the doorway, weighs in: “You guys suck!” Euronymous and his bandmates continue to look fairly dorky: running away from the police early on, they look like Wayne and Garth and their buddies. Euronymous tries out what will become his trademark stage makeup, basically a lugubrious, super-simplified retread of KISS black and white. “Do I look evil?” he asks Sis. “I like it!” she perkily replies.

We go further into the preposterous when Mayhem acquire a new singer, Pelle from Sweden (a very amusing Jack Kilmer), who goes by the name of “Dead” and takes his morbidity very seriously indeed: his bandmates know he’s the real thing when he insists they stop their car so that he can get out and sniff a dead fox, inhaling its effluvia like an appreciative sommelier. He sleeps in a coffin, and tends to go into catatonic stupors—often standing upright—from which he can only be roused by the thought of killing cats. Mayhem hate non-depressive competitors—“All they do is celebrate life and party”—and go about their own performances with a certain gusto. Pelle slices his arm onstage, bandaging himself with gaffer tape afterwards, while fans heartily chomp on pig’s heads thrown into the crowd. It’s all played for Åkerland for jovial fun—we all did crazy things in our youth, right?—with Culkin’s Euronymous intermittently offering a breathlessly bemused voiceover on the band’s rise to infamy.

The moment at which Åkerland’s narrative tone really comes unstuck is when something truly dreadful happens. Pelle shows he’s not just kidding about depression, and kills himself in a feat of spectacular morbid showmanship—at least, that’s how Åkerlund presents it, macabre special effects and all. Blundering onto the scene, a confused Øystein runs in horror, then comes back to take photos that, he’s convinced, will be the band’s golden ticket to legend. It’s a scene of absolute horror that’s played as a gorehound production number, and the fact that Øystein is behaving either like a sociopath or merely a callous opportunist seems beside the point for the movie: it’s a scene that would take real chilly delicacy to carry off, or a truly bleak sense of nightmare black comedy, but Åkerlund treats it as just a lurid highlight in Mayhem’s gonzo legend.

The next figure to enter the story is a shy young man from Bergen, called Kristian (Emory Cohen), later known as Varg, the Count, or Greifi Grishnackh, a proper catarrhal throat-clearer of a name. At their first meeting, Euronymous shames Kristian for wearing a patch on his denim jacket celebrating mainstream metal veterans Scorpions: like many a kid shamed at a tender age by music snobs, Kristian will never get over it. He returns later, when Euronymous is lording it over his own dad-funded record store and label, and shocks him with a self-made demo tape that shows Varg, recording as Burzum, to be the real thing. The two become both rivals and bandmates, Varg joining Mayhem as bassist; much of the ensuing comedy involves gauche Kristian outstripping his erstwhile mentor and tormentor as a dark idol of the Norwegian metal scene. He also becomes a world-class dickhead, an arrogant strutting local genius and priapic lunk (“His creativity was exploding,” marvels Euronymous. “He fucked everything that moved”).

There’s some prime comic idiocy which Åkerlund treats fairly amusingly. Decking his squeaky-clean white apartment with swastikas and demonic accoutrements to welcome the press, Varg bumps his head on an uncomfortably placed goat’s skull. “Pagan, Satanist, Nazi—that’s a pretty broad belief system,” a journalist comments, before Varg’s sidekick comes in with refreshments: “Tea, anyone?”

A series of horrors then ensues, however, which Åkerlund really doesn’t know how to handle. Varg and Euronymous go on a spree of burning down churches because the Church, as they see it, is a baleful influence on Norwegian society, “oppressing us with their kindness and their goodness” (their supposedly Satanic inversion of the common worldview comes across more like the Addams Family, beaming with relief when rainclouds gather). Varg has a time bomb ready for one of the attacks (“10, 9, 8, 7, 6, 6, 6…”). The arson is treated as a music-video production number (did Åkerlund really need that photogenic raven in front of the flames?); it’s only after a moment that you notice that the film hasn’t told us whether anyone was killed or injured in the process.

Maybe to have such qualms is to take their terrorism too literally, when here it’s being presented more or less as an expression of radical showmanship. But there are other things that the film really doesn’t have a handle on, like the neo-Nazi badinage among some of the characters; it’s very hard to care about characters, even when they’re depicted as born-again bad ’uns, when they’re cracking jokes about gas chambers. And there’s one moment that’s really handled with utter ineptitude: a scene in which one of the circle, “Faust” (Valter Skårsgard), is subject to a clumsy gay pick-up and reacts with shocking violence.

It’s whenever things get real—nastily, depressingly real—that the film is most out of its depth. Faust is forever seen watching gruesome horror movies on TV, and the actual killings in the film are lavish with scarlet blood, in a retro video-slasher style, as if to alert us to the discrepancy between death fantasy and things getting real. But these moments only make it feel as if Lords of Chaos is concealing real horror, and the moral vacuity that’s at the heart of this story, behind a reassuring veneer of genre sensationalism.

What makes the film watchable is the acting, which at times has a real comic edge, plus a touch of poignancy. The principal characters all have delusions of grandeur, and banal realities to offset them, and Cohen’s Kristian is defined quite touchingly by the clash between his chubby-faced sneer and the silken L’Oréal locks that frame it. Rory Culkin is saddled with some shockingly clunky voiceover lines—“Everything was taken to a new level. This is not what I signed up for”—but he generally offers a sweet, comic, and rather touching depiction of a young man caught between his death-eater delusions and his nebbishy true self. It’s a pleasure watching his Øystein/Euronymous get increasingly flustered and out of his depth, especially when he’s gabbling away nervously in his sensible little spectacles, or with a feeble little moustache bristling. Singer-scenester Sky Ferreira is in here too as Øystein’s girlfriend, basically on hand to raise a skeptical eyebrow, and to undress sporadically: it’s a derisory role, which only underlines that the relationship between Euronymous and Varg is a frustrated male love affair, of the sort which—among hyper-macho, right-wing homophobes—is likely to end badly.

Lords of Chaos comes across increasingly like a teenage “moral panic” exploiter of the ’50s, at once reveling in the excess and waving a teacherly warning finger. It could almost be telling us, Stop dressing in black, kids, and try listening to something more wholesome—Roxette, perhaps.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes its Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.