Film of the Week: A White, White Day

A White, White Day (Hlynur Pálmason, 2019)

Hlynur Pálmason’s Icelandic drama A White, White Day is a stark, controlled psychological thriller that unpicks its hero’s troubled soul with forensic coolness. Yet at the same time, it’s also an exercise in highly stylized film language that every now and then makes you sit up in amazement at the boldness of the directorial flourishes. In theory, this shouldn’t work: what Pálmason does ought to “take you out of the story,” as the phrase goes. What it does, rather, is “put you into the film”– that is, deeper into the filmmaking. We tend not to worry about style being disruptive in written fiction—at least, we don’t if we’ve learned any of the lessons of literary modernism—so why should we in cinema? But Pálmason, I think, wants us to worry, and the anxiety we feel about whether A White, White Day is telling its story properly—whether it’s efficiently bringing us closer to its protagonist without inappropriate detour—is all part of the strategy of this bold, troubling drama.

Writer-director Pálmason—following up his 2017 debut Winter Brothers—knows how to get a tight grip on the viewer’s nerves right from the start, although in a sense he’s dealing with obvious material. As the camera follows a car on a winding road, deep in white winter fog, of course it’s a given that something drastic will happen—and of course our nails will be digging into the front of our seats as we watch. A tension-building shot like this is in one sense facile—yet it’s the patience with which Pálmason keeps us waiting, then delivers the shot’s payoff just when the tension is intolerable, that show his command.

That absolute assurance continues to be evident in the way Pálmason keeps us waiting for an explanation of what we’ve just seen. Instead, he gives us the first of a number of montages, using jump cuts to show us a house shot by a locked camera in a rural landscape across a stretch of time. It’s hard to tell whether we’re skipping weeks, seasons, years even, as we watch a large industrial-looking building undergo a series of changes, some sort of renovation process, as the mountains in the background are obscured by mist then abruptly return; snow covers the landscape then departs in a split second, horses and cars appear, vanish, reappear.

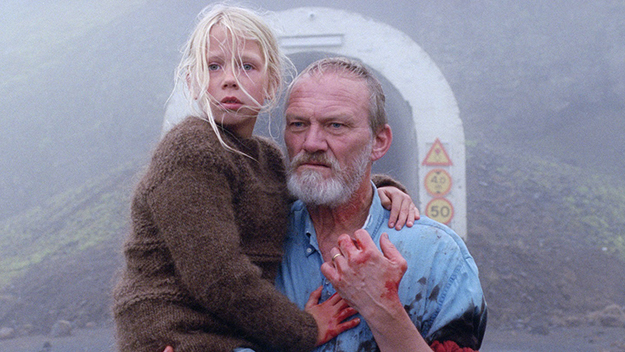

Pálmason starts giving us narrative landmarks gradually, as we meet the inhabitants of the house: a sturdy man in late middle-age named Ingimundur (Ingvar Sigurdsson) and a little girl named Salka, his 8-year-old granddaughter (played by the director’s daughter Ída Mekkin Hlynsdóttir), who occasionally lives with him in the house. Eventually, we gather that Ingimundur is the police chief in a small Icelandic rural community, currently on leave and traumatized by grief since his wife’s death in a car crash. He’s now renovating the building on family land, and occasionally visiting a local therapist—although the taciturn Ingimundur isn’t really playing. Instead, the absurdly voluble shrink constantly fires questions at him, but only gets an answer when he asks, “What do you want? Ingimundur replies, “To build a house.” “What don’t you want?” the shrink asks. Ingimundur: “To stop building it.”

Ingimundur’s work in constant progress is about constructing a physical shell that complements his psychic exoskeleton. But the crumbling of his defenses begins when he finds a library book and some photos among his slate wife’s effects, and starts to suspect that she was having an affair. Ingmundir becomes obsessed with finding out the truth, and starts to stalk his neighbor Olgeir (Hilmir Snær Guðnason), the suspected lover.

Things stay quietly on an even keel for a long time, as if the film and its protagonist’s emotions were suspended in deep freeze; the solemn, near-silent Ingimundur seems almost a parody of all our stereotypes of chilly Nordic masculinity. Sigurdsson, whose Icelandic films include Of Horses and Men and Jar City, somewhat resembles the younger Richard Harris or ’60s British stalwart Harry Andrews; he looks rather as if he’s been hewn out of the inert solidity of the local rock-faces, and he’s cast brilliantly to this effect. Eventually, however, Ingimundur’s dam of welled-up emotions bursts, to explosive but somewhat comic effect. There’s another scene with the therapist, who hasn’t been able to attend his consulting room, so instead speaks over a screen with a faulty connection, firing questions at his patient, but not registering his response, and Ingimundur’s patience finally snaps, spectacularly—something that will be more than understandable to anyone who’s spent a lot of the lockdown period on Zoom. Pálmason and DP Maria von Hausswolff also make unsettling use of screens as a leitmotif: police surveillance shots of the local roads, as well as windows, frames, all kinds of rectangles signifying separation, enclosure, anxiety-inducing containment.

Ingimundur then throws his weight around at the police station, showing his colleagues who’s still boss: a key takeaway of this scene being that you should never pull out a Mace spray unless you know absolutely how to use it. The drama heads right on to not one but two absolutely nerve-racking confrontation scenes—the second an alarming turning of tables—and then to a payoff in a long single take in almost total darkness, involving a simple but hugely resonant act of redemption.

You could easily imagine a version of this film in which Pálmason had decided simply to tell the story with no directorial frills, and it would be still be extremely strong, just some seven or eight minutes shorter. But include his digressions and you get something really quite extraordinary: along with those jump-cut sequences on the house, a montage of “portrait” shots of key and minor players all gazing at the camera; a set of close-ups of miscellaneous objects and details that all play a key part, narratively or (perhaps) symbolically; and an absolutely remarkable episode involving a rock. The boulder has fallen downhill in a landslide and is lying in the middle of the road: Ingimundur picks it up and tosses it away; in a series of shots, we see it roll down the hillside, down further still, fly off a cliff edge into the sea… and down through the water, until it lands softly on the seabed. There’s no obvious narrative purpose to this sequence, but it’s immensely arresting, and it’s up to us to decide what we want to do with it: whether to read it as a metaphor for what’s happening emotionally to Ingimundur, or for the way that things and actions in their concreteness entail irreversible consequences, or to see it simply as an exuberant touch by a director injecting a gratuitous flourish of stylistic rhetoric into an otherwise functional narrative. However you read it, it’s an intensely audacious and original touch—although “touch” would suggest that it’s merely a superfluous add-on, when really it’s integral to the film’s very distinctive grammar.

Another thing that’s original is the way the film treats childhood, which to say altogether unsentimentally. As Salka, young Hlynsdóttir gives one of the most striking child performances I’ve seen recently, one that doesn’t allow her character either to be treated as adorable nor fetishized as a precociously knowing “wise child”; instead, Hlynsdóttir’s solemn, serious demeanor (when she’s not laughing or smiling, that is) makes Salka come across at once as a real vulnerable child, but also as an embodiment of her grandfather’s pitiless conscience. There’s an extraordinary moment when the old man—loving but with not an iota of softness about him—makes the girl cry, then looks at her as if he never knew that 8-year-olds did that sort of thing.

Hlynsdóttir is particularly good—and brilliantly directed by her dad—in a scene in which Salka asks her granddad to tell her a scary bedtime story. He obliges by spinning a ghastly tale of grave-robbing and cannibalism, as the camera pushes in on the child’s face, her eyes opening wider and wider. You think this must surely be the worst episode of misguided child-minding in cinema since Michael Powell played with lizards in Peeping Tom—until Salka snaps furiously at Ingimundur, then bursts out laughing, and you realize that this is simply one way of teaching children to deal with fear (and before the end of the film, Salka will need to know how to deal with it).

This is a small but intensely idiosyncratic film, and only possibly makes a false move in the very final sequence. Even then, it wins back points here by using a Leonard Cohen song, and while that has become a terrible cliché in recent years (most egregiously in Elia Suleiman’s recent It Must Be Heaven), Pálmason goes for a decidedly off-kilter choice, the ’50s-styled “Memories” from Death of a Ladies Man. A White, White Day is now showing online in FLC’s Virtual Cinema program, and it will bring you a bracing chill in this strangest of springtimes.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes the Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.