Film of the Week: 63 Up

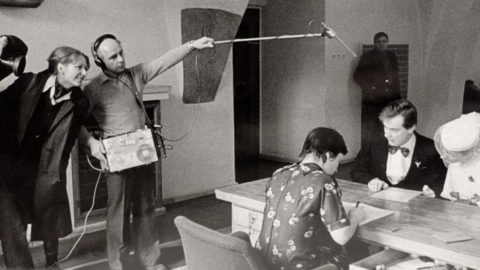

63 Up is the latest episode of the most extraordinary sustained experiment in documentary history. In 1964, director Paul Almond profiled a group of fourteen 7-year-old British children from diverse backgrounds in a program for U.K.’s Granada Television called 7 Up. Since then, 7 Up’s researcher, Michael Apted—who also went on to carve out an eminent career as a transatlantic feature director—has continued to film the subjects every seven years, in a series of avidly followed programs that have allowed British society to watch itself change over decades.

With 63 Up, you wonder whether you’re seeing simply the latest episode in the series, or its culmination: some of the original subjects have dropped out, one has died, all are at an age when they are beginning seriously to contemplate their mortality. One man, facing serious illness, notes that these days he is only focusing on “short-term futures”—by contrast with their younger selves for whom, in varying degrees, infinite possibilities seemed to beckon. Because of this sense of an approaching end—in a world which, in any case, is tending to see the future in apocalyptic terms—63 Up may be the most revealing episode yet. It is certainly the most moving—especially if, like this viewer, you happen to be closer to the age of the subjects than is strictly comfortable. When one subject comments today that the series is the story of Everyman, he’s not kidding—but it’s even more so, now that Everyman’s story is nearing its inevitable conclusion.

Shown on British TV earlier this year in three hour-long episodes, 63 Up is now released in the U.S. as a 140-minute feature. It consists of separate sections on 13 of the original subjects: one, Charles Furneaux, who himself became a documentary film-maker, dropped out after 21 Up, while Suzy Lusk, very briefly profiled here, declined to take part in this episode, which recaps her life up to age 56. In the case of Lynn Johnson, we follow her progress as a librarian and committed educationalist up to the age of 56, and we’re eager to find out what happened next to the woman who comes across as the most passionately socially committed of the group; we then learn that she died in 2013, and see her family members reminisce about her and her legacy.

The recurrent theme in Apted’s voiceover, and the series’ leitmotif since it began, is a variant on the Jesuits’ motto: here, it becomes, “Show me the child at 7 and I will show you the man.” In many cases, the men and women of today not only recognize themselves in their 7-year-old selves, but feel that their whole character, and even their future, are already inscribed in the children in seed form.

The other key is class. The subjects were originally chosen partly with a view to illustrating the British class system. There were a number of working-class children, some from a school in London’s East End, plus two boys from a children’s home; some whose background could be considered more middle-class; and some whose childhood manner shocks today in terms of the assumptions of privilege that some ostentatiously display even at 7. One lad, knowing he’s destined for the exclusive English public school system (not public schools in the U.S. sense, but expensive fee-paying private schools), confidently asserts that he’ll attend Charterhouse School, then the Cambridge college Trinity Hall: he did indeed become a successful lawyer. John Brisby is an outrageously opinionated sexist at 7, and a terrible snob: he believes that schools should be fee-paying, because otherwise “they would be so nasty and crowded.” At 14, he declares ambitions to “political power.” At 21, he’s a cocky lounge lizard in a three-piece suit, lounging in a manner reminiscent of the vile Conservative mandarin Jacob Rees-Mogg. Today, however, after a successful law career, he seems a much more humble, compassionate person, more complex than those earlier images suggest: he reminds us that his mother was Bulgarian, his grandfather was “a revolutionary,” and he has long been engaged in humanitarian work. Altogether likeable now, he feels that the program used him to represent the “posh boy” archetype. Whether or not he was accurately represented back then, John seen at 63 offers a reminder that it may take most of us a lifetime to really accumulate nuance of character.

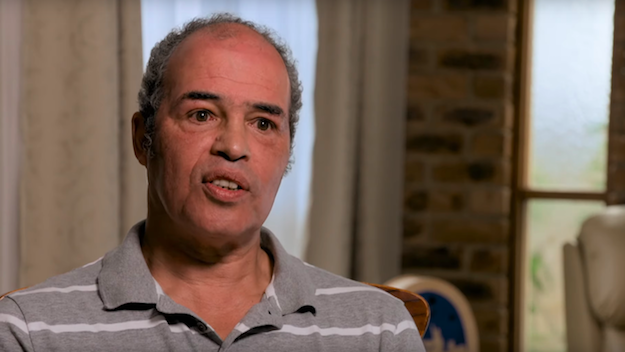

It’s by no means certain that all the posh kids had it easy, although some seem to have glided through life and career smoothly. Bruce Balden, a serious, quiet man, now stout and badger-like, is seen at 7 at his public school; he later recalls being beaten regularly, and not always knowing why. As a result, he says, he learned to live with what he calls a “restricted emotional state.” His experience chimes with that of two boys who were first filmed in a children’s home—Paul Kilgerman, who eventually emigrated to Australia, and Symon Basterfield. Symon is mixed-race and the program’s only non-white subject, something which says more about the original film’s assumptions than it does about the make-up of early ’60s Britain. Their experience of the home, one of them says, was that it was “regimented,” although what it seems to have left the pair with, in the short term at least, was not emotional restriction but a lack of confidence and self-worth. At 21, Symon worked in a meat freezing facility; Apted is heard asking whether he doesn’t consider himself worth more. As Symon matures, his movie star enduring robustly, he at last finds his distinctive calling as a dedicated foster parent, committed to giving the children in his care the support he was himself denied.

While some subjects come across as characters, and well aware of it, others are less magnetic, their lives perhaps lacking in what we’d consider Narrative—although you consistently ask what dramas are happening in the gaps between episodes, in the secret moments of their lives that they perhaps prefer not to confide to the camera. One of the characters, capital C, is cheerfully pugnacious East End boy Tony Walker. His personality and his progress leave him open to a degree of caricature as a loveable rogue, which he’s only too happy to play up to (“I was a cheeky chappie and I’ll accept that”). As a boy he dreamed of being a jockey, and competed at Kempton Park racetrack alongside the legendary Lester Piggott; soon after, he became a cab driver. Today, he has a sideline playing bit parts in movies, and grins about the fellow cabbie who once wanted his autograph rather than Buzz Aldrin’s. Tony seems steeped in self-awareness, rather than necessarily self-knowledge—or perhaps he’s just supremely talented at presenting himself to the camera. Of all the subjects, he seems the most aware of his public image—although there’s something significantly different between the experiences of these people growing up under serious-minded, sustained and intermittent, quasi-sociological scrutiny, and the generations of reality TV subjects who have become abruptly exposed to intense pseudo-fame, then suddenly dropped.

Who knows whether the program itself, and the ensuing public scrutiny, caused damage to any of the participants. Peter Davies talks about being caricatured by the right-wing British press as “an angry young Red”; he dropped out of the series for years, but returned at 56, and is now seen happily pursuing his part-time career as a folk artist, working on a novel, and still expressing political anger. It’s harder to gauge the series’ effect on Neil Hughes, who over the years has intensely captured the audience’s imagination and empathy. At 7 and 14, this Liverpool boy, who dreamed of being an astronaut was the brightest, most articulate, most charismatic of the lot; the future was clearly his, not by class entitlement but by dint of the energy and hope he radiated. At 21, he had dropped out of university and worked on a building site; at 28, he was homeless in Scotland. Eventually he came to London, became a Liberal Democrat councilor, and has been politically active ever since; he now lives much of the time in France and practices as a lay minister. In some ways, life worked out for him, in others not: he has coped with depression and mental illness for most of his life. Already at 42, he has the stark, agonized manner of a Dostoevsky character; today, he blames his problems partly on parents who were unable to give him, as he said at 21, “any policy for living.”

Neil’s experience will be a Rorschach test for viewers: some will see it as a terrible story of disappointment and lost possibilities; I prefer to read it as one of tenacious realism and survival against brutal odds. Some of these people’s stories come across as CVs, family chronicles, or chains of unconnected anecdote; Neil’s is the one that truly comes across like a novel, perhaps an exemplary one that we can all learn from.

We also learn a lot from East End girl Jackie Bassett, whom we follow through motherhood, family tragedy, illness today, and an earlier succession of Princess Di hairdos. She’s a fantastically strong presence, the most rebellious of the group; at 21, she talked determinedly about not wanting a sedate, servile marriage, and she stuck to her guns. She’s the one who challenges Apted on his assumptions—as she has done for years— asking him today why he quizzed the girls about marriage and men rather than politics: “But the time we hit 21, I thought you’d have a better idea of how the world works, you still asked us the most mundane domestic questions.” It’s a credit to Apted’s nerve that he includes her sharp criticism.

The series’ initial assumptions about gender, class, privilege, and race have become more pressing over the years; 63 Up’s revelations about class and privilege are particularly acute today, now that we’re becoming aware that the old system remains horribly entrenched in the form of Boris Johnson, David Cameron, and co., and the grip they still exert on the U.K.’s psyche. 63 Up is also eloquent about—and is perhaps a last survivor of—a time when British television documentary had serious aspirations to explore and illuminate, rather than being forced by commissioners to simply expose for entertainment value (even that most destructively rule-changing TV confection Big Brother originally claimed ambitions to sociological insight).

Now that it has run its course, or almost, the series also begs questions in terms of its assumptions, and ours, about what we can learn from children, about the way we read them as revealing mirrors of the future. The overall project has arguably raised more questions about society, and about life, than any other undertaking in TV history—and one imagines that, if we get to follow these people into their seventies, the insights will become still more profound and more moving. Hearing these stories of bereavement, illness, personal catastrophe, and endurance, seeing the lines written on these once fresh faces, you might see 63 Up as a terrible reminder of mortality; but in their own ways, these cases all are stories of endurance, survival, strength. Gaining in depth with every episode, the 7 Up project has become not a memento mori, but its opposite—a memento vitae.

Jonathan Romney is a contributing editor to Film Comment and writes the Film of the Week column. He is a member of the London Film Critics Circle.