Festivals: Wavelengths at TIFF

What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?

For the past 12 or so years, fall has offered the opportunity to binge-watch experimental film. I used to cram it all in at the New York Film Festival’s Projections (né Views from the Avant-Garde and its sister program Walking Picture Palace), but in recent years I’ve spread it out a bit with a headstart at Wavelengths in the Toronto International Film Festival. I’ve glazed over while watching too many movies on my laptop only to be stunned by a later theatrical viewing, to miss a chance to see this work on the big screen. I’d come to view this tradition as a necessary evil. Watching eight hours of experimental films in a day is arguably the worst way to do it. I found myself walking away from a day of screenings despairing over prevailing trends, riled up about unfortunate programmatic juxtapositions, or just plain confused. I’d often go back to a film months later and realize I hadn’t given it a fair shake or had no memory of it at all. Luckily, the context in which I was programming allowed me to sit with the films, to see what I was still thinking about months later and to revisit with fresh eyes. Which is all to say, writing an immediate wrap-up of this year’s Wavelengths is completely at odds with how I’ve learned to digest the program.

The prospect of assessing Roberto Minervini’s new film in this context seemed especially daunting. I can’t think of many other filmmakers that I approach with such equal measures of skepticism and admiration. On first viewing, I admit I can’t quite get my head around how all the pieces are working together in What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire?. This may have to do with the presence of Judy Hill, a supernova, whose radical openness and empathy dominated my first viewing. In the past I have found the access Minervini gains from his subjects unnerving and possibly untoward, but in Hill he’s found a true collaborator with the self-possession to be an endlessly dynamic transformative force.

In my corner of the world, What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? seemed like one of the films of the festival, topping everyone’s list of priority viewing and dominating small talk along with the new Claire Denis or Peter Farrelly. This was the first time that I’d ever limited myself to a single section at a festival and it made me acutely aware of the arbitrariness of some of the slotting. While I’ve always viewed selection for Wavelengths as a seal of approval, I suppose it could also serve as a word of warning for some audiences. In the case of both What You Gonna Do When the World’s on Fire? or Igor Drljača’s excellent documentary debut The Stone Speakers, exclusion from the documentary main slate serves to focus attention on that section’s conservative bent. There were certain narrative headscratchers in Wavelengths as well: why weren’t Bi Gan’s virtuosic Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Ulrich Kohler’s keen In My Room (both genre-adjacent films by up-and coming directors, Cannes-approved, widely lauded…) screening alongside more mainstream world cinematic fare?

Maybe it’s naive to assume thematics come into play when sectioning at a festival as large and commercially minded as TIFF, but I was grateful to have seen Kohler’s end-of-the-world relationship parable alongside Helena Wittmann’s Ada Kaleh and Beatrice Gibson’s I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead, two revelatory short films dealing with apocalypse-era domesticity. Named for a lost island in the Danube, an Ottoman Turkish enclave in Romania that changed hands many times throughout the 19th and 20th century before being submerged, Ada Kalah observes an urban apartment as street sounds signal the passage of an indeterminate amount of time. The structure is simple and hypnotic: Wittmann pans across an apartment, catching a changing roster of inhabitants in conversation, in repose, at work, and in absentia, forever in a even, idyllic afternoon light. Prefaced with polyglot narration about an unsteady world, Wittmann captures young bohemia in suffocating amber. Perhaps they would benefit from the shot in the arm of Gibson’s I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead. A departure for Gibson, I Hope I’m Loud When I’m Dead was one of the bracing surprises of this year’s program. It flirts with cliches which it immediately upends (or earns), careens in new directions, and ultimately delivers true catharsis. It’s a film that makes the case for art being alive and essential in a world that is relentlessly deadening.

Polly One

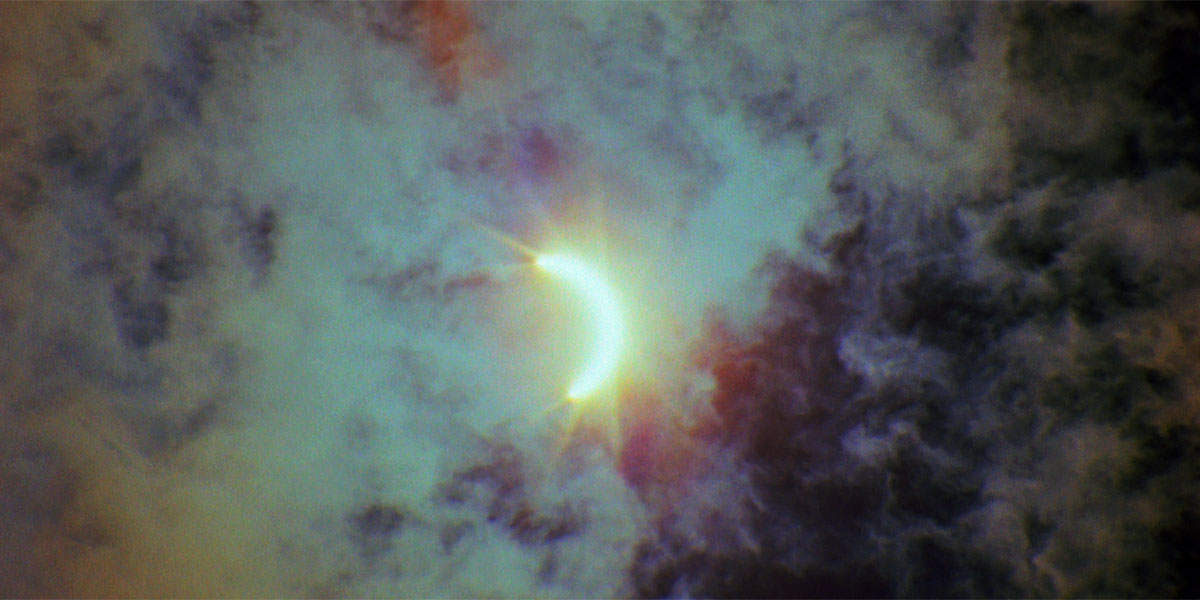

Gibson’s essay on motherhood, political engagement, art, and community capped off a program that included two restorations of obscure feminist romps: Lisa Baumgardner’s Girl Pack, a No Wave–era portrait of punk girls in the East Village in the vein of Vivienne Dick, and Maria Lassnig’s Alice, a hilarious paean to a young libertine. Programmers Andrea Picard and Jesse Cummings should be commended for carefully calibrating the shorts programs around resonances without bulldozing the audience with overwrought theses. Inspired groupings like the one mentioned above, or Kevin Jerome Everson’s eclipse film Polly One (a study in color and movement around a shared cosmic event) with Sky Hopinka’s Fainting Spells (an evocation of landscape and myth across corporeal and spiritual planes) or Simon Liu’s Fallen Arches (a diaristic travelogue, temporally flattened though superimposition) with Karissa Hahn’s Please Step Out of the Frame (a mise-en-abyme self-portrait mediated through analog, digital, and the limitations of proprietary software) felt generative to the work and generous to the artists.

Perhaps it was my own shifted perspective, but this year’s program seemed especially vital, as if some of the ruts of the past few years have finally been shaken loose. Jodie Mack’s Hoarders Without Borders injected life into the stale avant-garde microgenre of archival materials presented in pleasing arrays (usually interrogating a political history). In Mack’s hands, the work of creating these tableaus is laid bare. A time-lapse reveals arms swarming around a pedestal as a blur of objects are laid out for documentation; the image moves into focus as trays slide into their drawers and out of focus again. As many films in this mode tell us more didactically, institutions have the power to illuminate but also the power to obscure.

Nellie Killian is a film programmer based in New York.