Festivals: Sundance 2017

78/52

The essential statistics: I spent nine days at the Sundance Film Festival, averaged about 3.33 feature films a day with panels and VR “experiences” crammed in the interstices, trudged through approximately 10 feet of accumulated snow, banged up two elbows, bravely overcame one head cold (which was going around) and one hangover (ditto), tied for third in bar trivia, made tentative plans with several dozen people and carried out maybe three, and answered the question “How’s your festival?” 300,000 times.

So how was it? Oh, you know, about how they always are. There were a great many “sympathetic” movies sunk by ineptitude whose names it’s best not to mention, and a few unsympathetic ones overburdened by vapid virtuosity—by the way, did you hear that Thoroughbred, the touted first feature of playwright Cory Finley starring Anya Taylor-Joy and Olivia Cooke as two posh Connecticut teens who team to pull off the perfect murder, went to Focus Features for a cool $5 million? (Presumably they’re banking on its being a modern-day Heathers, though for this viewer it functioned as a reminder that all I want is cool movies like it out of my life.) As for out-of-the-blue windfalls, well, Alexandre O. Philippe’s making-of documentary 78/52, caught at a time-killing press-and-industry screening, gets more juice than anyone might reasonably expect out of a worked-over topic like Alfred Hitchcock—specifically, the shower murder in Psycho. It’s refreshingly light on the pseudo-sociology and heavy on the nuts-and-bolts shop talk, the interviewees being mostly editors, sound designers, and—sure, why not?—Elijah Wood, breaking down the scrupulous detailing and patterning built into Hitchcock’s movie, all of which can be found in miniature in its central setpiece. I left thoroughly convinced that, yes, Hitch was very good at doing that sort of thing, and then set out to be reminded over and over again that such master-builder intelligence is pretty thin on the ground.

Much as I would like to report on the utterly unexpected discoveries, new beginnings, and great leaps forward that I experienced at Sundance, the truth of the matter is that I mostly enjoyed the films that I had some expectation of enjoying, and that at least a handful of these were made by people with whom I am passing friendly from New York City. It’s a fact that NYC generally, and the borough of Brooklyn specifically, were proportionately overrepresented at Sundance, as they are in popular culture as a whole. I saw more brownstones during eight days in Park City than I do living a month in unfashionable vinyl-siding Queens.

Golden Exits

Alex Ross Perry’s Golden Exits is so New York that it features pillow shots of the Gowanus Canal and Adam “Ad-Rock” Horovitz noshing on a side order of pickles while taking a non-break lunch break hunched at his desk. Horovitz is at the center of a roundelay of variously personally and emotionally thwarted New Yorkers in Golden Exits, an exercise in the network narrative—a form whose great potential has unfortunately been overshadowed by various truly abominable “We are all connected” movies in still-recent memory, and which has been redeemed by the attention of bona fide artists like Kelly Reichardt in her Certain Women, a Sundance standout last year. The dramatis personae of Perry’s movie are mostly professionals in their mid-thirties and older. Horovitz plays Nick, a crabbed, antisocial archivist currently cataloguing the effects of a deceased publisher who happens to be the father of his wife (Chloë Sevigny), the project overseen by her hostile older sister (Mary-Louise Parker). This trio is matched by another: a recording studio owner, Buddy (Jason Schwartzman); his business partner and wife (Analeigh Tipton); and her sister (Lily Rabe). The destabilizing element in all of this is Naomi (Emily Browning), a 25-year-old Australian in town to work with Nick, and introduced in a lovely overture singing an a cappella rendition of Hello/Ace Frehley’s “New York Groove.”

Young and unattached, Naomi poses a threat to this small community of people who are neither, exactly, and Golden Exits explores the fragility of the house-of-cards lives built by these loosely tethered, childless adults—women in well-worn patterns of merciless self-analysis, men who get an illicit thrill from testing the breaking points of their fidelity. Both Nick and Buddy entertain their private fantasies about Naomi while only glancingly crossing paths and never knowing of the other’s designs—pointedly, everything doesn’t connect here, and the film’s structure is something like an unclosed circle. It’s a movie of things unspoken and desires suppressed, but happily free of self-effacing style, dignifying these non-happenings with a treatment worthy of high melodrama. Perry’s dialogue is declamatory and ice-water crisp; there’s a key scene late in the film that makes use of a splash of light reflected through stained glass on the wall above a stairwell that, in palette and staging, feels almost Sirkian; and Keegan DeWitt’s score is burrowing and richly insinuating.

The other network exercise of note this year was Dustin Guy Defa’s Person to Person, which likewise made a point of not connecting all of its dots—narratively, at least. The film is comprised of five distinct story strands, two braided together, the extra one flapping in the breeze, and all of them placed in intercut conversation with one another. Record collector Bene (Bene Coopersmith, star of Defa’s previous short of the same name) goes on the hunt for a rare edition of Bird Blows the Blues while his despondent roommate (George Sample III) handles the fallout of an impulsive, uncharacteristic venture into revenge-porn. Meanwhile, across town, tabloid veteran (Michael Cera) leads a cub reporter (Abbi Jacobson) in an investigation of a suspicious suicide, sniffing around for clues at a Chinatown clock repair shop that acts more like a hang-out for proprietor Jimmy (Philip Baker Hall) and his elderly pals. Finally, we have a Manhattan high schooler, Wendy (Tavi Gevinson), who, during a day of playing hookie, is working through typical high schooler issues—deciding if she prefers sex with boys or girls, or if she’s capable absorb the incredible richness of the passing moment without smothering the experience, you know, things like that.

Beach Rats

Odd to say of a movie that dedicates a fair amount of its runtime to loafing around during the mid-afternoon and shooting the shit, but there’s a real sense of urgency about Person to Person, a plenitude that is very winning, and the film contains a couple of close-ups—of Sample, destitute and begging forgiveness, of Gevinson suddenly aflutter and overwhelmed during an awkward make-out—that access surprising depths of feeling. Defa resembles Perry in his interest in experimentation with the network narrative form, and he’s likewise drawn to the milieu of small business concerns, but the worldviews expressed in their films couldn’t be more starkly contrasted. Perry’s series of studies in quiet desperation ends with an image of upper middle-class isolation and the dolorous question “Is that all there is?”, while Defa’s movie ends on a spontaneous eruption of friendship and a dance party.

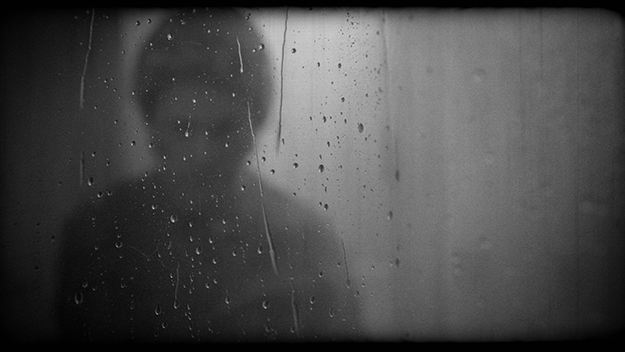

Eliza Hittman’s Beach Rats, rounding out the New York contingent, concludes on a far more ambivalent note, ambivalence being something like the movie’s presiding tone. The film’s protagonist, Frankie (Harris Dickinson), spends his empty days halfheartedly cruising chicks for form’s sake on Sheepshead Bay and Gerritsen Beach with his friends, a great gallery of hard cases plucked from the city’s handball courts, and his nights basking in the attention he finds in gay chatrooms where, when a potential partner asks what he’s into, he replies quite candidly, “I don’t know what I like.” Beach Rats is the follow-up to Hittman’s 2013 It Felt Like Love, a study in (premature) female sexual awakening in the director’s native country, the tidewater precincts of ungentrified Brooklyn, and like that film, practices a curious, caressing cinematographic style which renders the environment as a sensorial midway. (The use of boardwalk fireworks cleaves close to cliché, but the poetic possibilities of vaping have never been explored quite so well as they are here.) It’s a low-light, largely nocturnal movie, and the 16mm cinematography by Hélène Louvart, whose credits include Larry Clark’s high masterpiece The Smell of Us, hovers on the edge of darkness, bringing out an appropriately sandy grit. A last-act turn takes things in a squeamish direction, almost as uncomfortable as the post-screening Q&A, which involved the director facing a litany of what was essentially the same question: how did she, a woman, justify herself in telling a gay man’s story? This continued after Hittman quite reasonably answered that many of her favorite movies about women were directed by men, which you might think would’ve put rest to the thing, but… O brave new era of rigid essentialism in the arts, where creative license and artistic empathy doesn’t extend a centimeter outside of the creator’s given identity!

And while such fine points were being debated in Park City, the Republic burned. A certain air of foreboding was added to this edition of the festival by the fact that the inauguration of Donald John Trump, who’d cruised to victory on a ticket of “refreshing” straight-talk boorishness, took place on its first full day, while I was mucking about at the press preview of the New Horizons virtual reality section. (This, incidentally, supported a long-standing hunch of mine, that VR technology and artificial immersive environments are being developed in response to an inchoate psychic need to escape a world rendered increasingly unlivable.) Away from the action in Park City, some marched, and some filed dispatches from the scene fretted over how the films at Sundance could operate as an avenue for effective resistance—which, of course, it was taken for granted that they could do.

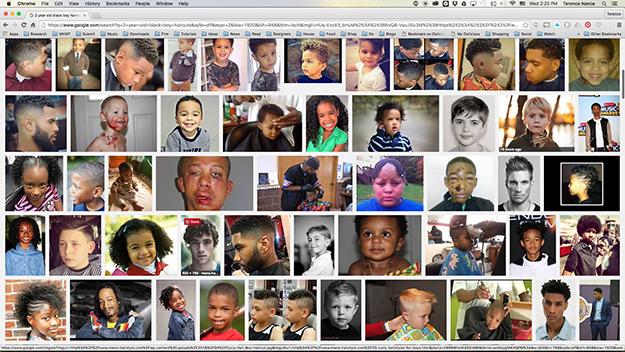

18 Black Girls / Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and Are Thus Spiritual Machines: $X in an Edition of $97 Quadrillion

Amid all of this I was grateful to encounter Terence Nance’s web-browsing-as-performance piece 18 Black Girls / Boys Ages 1-18 Who Have Arrived at the Singularity and Are Thus Spiritual Machines: $X in an Edition of $97 Quadrillion. Nance is perhaps best known for his 2012 feature An Oversimplification of Her Beauty, a dissection of a 2006 student short wallowing in unreciprocated romance and an exegesis of the motives for its creation, attempted from the vantage of some years down the line. That movie is a literally unrepeatable act, and Nance wisely hasn’t sought to repeat it, instead launching off into a half-dozen different directions at once, his practice encompassing short films, gestating features, a proposed TV pilot, and now web browsing-as-public-performance. With laptop desktop projected for an audience to see, Nance, using a search engine, enters the prompt “One-year-old black boy” (or girl, depending on the performance), from there counting up chronologically to “eighteen-year-old black boy,” and along the way clicking hither and tither through the autocomplete fills and top results. The resulting narrative moves from the precious to the petrifying, from a “Juju on that Beat” dance on the Ellen Show and a reading of Countee Cullen’s “Hey, Black Child” to Tamir Rice and “16-Year Old Black Trump Supporter Schools Black Lives Mater Moron,” and as Nance surfs, his brother, a beatmaker who performs as Norvis Jr., accompanies him, creating an improvised soundscape from loops and distortion of YouTube audio and text-to-speech. To this combination, which discourses on blackness as seen through the scrim of an algorithm, still another wrinkle was added by a chat sidebar with a visitor who identified himself as “Ta-Nehisi,” who traded thoughts with Nance about the possible pornography of police shooting videos before offering pragmatic advice about artistic resistance (“You not gonna save the world. You just ain’t.”).

Jem Cohen’s World Without End (No Reported Incidents), somewhat curiously slotted into the New Horizons section, certainly has no such pretentions. Coming in a bit short of an hour, it’s a portrait of the cities of the Thames estuary, including Southend-on-Sea, created through the accumulation of street scenes and long digressions on the subject of Baker Boy caps and the brief post-glam, pre-punk popularity of pub rock, and inasmuch as it has a political program, it’s on the side of the small and specific as opposed to the big and broad. The same might be said of Laura Dunn and Jef Sewell’s Look & See: A Portrait of Wendell Berry, which allows a soapbox for the 82-year-old Kentuckian agrarian theorist and poet Berry, who provides the film its eloquent narration but is otherwise something of a structuring absence, appearing on screen only in archival photographs and footage, including his 1977 debates with agribusiness-friendly Secretary of Agriculture Earl Butz. This was the year of Berry’s seminal The Unsettling of America: Culture and Agriculture, and more than 40 years before Anno 1 Era MAGA, Berry spoke to the decimation of rural America, offering a loving, holistic counterprogram for its renewal. The film’s evident reverence for its subject is contagious, and Berry himself is a calmly persuasive presence. His refusal to be photographed for the film stems, we’re told, from a basic mistrust of the medium of motion pictures, one point on which I’d have to part company—most of the time, at least.

Nick Pinkerton is a regular contributor to Film Comment and a member of the New York Film Critics Circle.