Festivals: Il Cinema Ritrovato

State Fair (Henry King, 1933)

For many years, Bologna’s Il Cinema Ritrovato has presented films with a legitimate sense of discovery and urgency, avoiding the common completist tendency toward the obscure. Rather than scraping the proverbial bottom of the barrel, every year this internationalist festival reiterates the historical necessity to question canons by bringing to light forgotten, underrated, vanished, or poetically exiled films and filmmakers. This year’s unanimously acclaimed surprise was the retrospective curated by the Iranian architect, jazz critic, and festival co-director Ehsan Khoshbakht dedicated to American filmmaker Henry King.

This decidedly lesser known director worked and lived through the passage from silent cinema to sound, converted to Catholicism while shooting on location in Italy (1924’s Romola), and made close to 120 films from 1915 to 1962. With the advent of sound, King signed with Fox and was, at least according to his own testimony in the 1978 documentary King of the Movies, the first filmmaker in the studio to secure final cut by contract. That would account for the singular and uncompromising vision of King’s films, which while adhering to the iconographic precepts of classical Hollywood bring to the fore the ambiguities and imperfections that happy endings usually leave out. Yet there is no polemical, let alone ideological intent in the cinema of Henry King. If outlaw directors from Fred Zinnemann to Allan Dwan, Nicholas Ray to John Huston, had consecrated their craft to the deconstruction of Hollywood mythology, King’s films are devoid of any confrontational aspect. If anything, they simply do not buy into the unrealistic optimism that continues to define the American spirit and are instead populated by fallible characters. Here are men and women who do not master their destiny but are mere victims of its cruel whims and cannot do much but accept the ethical impurity of life on earth.

In State Fair (1933) the director stages at once the genuine enthusiasm with which happiness is pursued and the existential void that its attainment can bring. The deceptively linear film follows the Frakes, a farming family, as they gear up to attend the Iowa state fair. Their trip is triumphant—Mr. Frake wins first prize for the biggest hog, Mrs. Frake is awarded the culinary prize—yet their joy and pride feels haunted by a sinister specter. Both their daughter and son have romantic affairs, which they dutifully decide to abandon out of Calvinist self-denial; Arthur Schopenhauer is even quoted by one character to evoke his idea of happiness as “mere relief” from the constant dissatisfaction of life. Beyond the microcosmic allegory of the state fair, a celebration of man’s earthly achievements, the director peeks into the desolation that lurks behind the protestant work ethic. For if the latter postulates that anything can be accomplished through hard work, in Henry King’s films the agency and determination of men is barely enough. In the 1937 disaster movie In Old Chicago the O’Leary family arrives in the titular city after having lost their father in an accident just before entering. In the promised land of opportunities, the O’Learys end up making it big and yet even their business empire won’t survive the 1871 fire that ravaged Chicago, taking 300 lives and destroying two million dollars’ worth of property. The final 30 minutes of the film are an operatic feast of destruction choreographed with spellbinding dexterity, the mythical parable from rags to riches pulverized into ashes. King’s clear-eyed vision of humans continued to the final years of his career, exploring moral righteousness and the arbitrariness of justice in the gothic Western The Bravados (1958): Gregory Peck stars as a man on a vengeful killing spree—the only problem being that the men he murders aren’t responsible for the crime he is convinced they have committed. After realizing it, he is provided with all the moral justification he needs by a priest, before walking into one of the most ambiguous happy endings in the history of cinema.

Ouaga, Capitale du Cinéma (Mohamed Challouf, 2000)

To celebrate 50 years of FESPACO, the first film festival ever to be organized in sub-Saharan Africa, Il Cinema Ritrovato curated a program dedicated more to its spirit than its cinematic output alone. From its very inception in fact, FESPACO’s significance was never limited to what appeared on screens. Born at the crest of the long wave of anti-colonial struggles that had liberated most of the African continent from European rule, the festival immediately incarnated the pan-African hope of a self-determined continent in which culture was to play a primary role. Aside from offering an overview of the festival’s roots and political essence, the beautiful documentary Ouaga, Capitale du Cinéma (2000) by Mohamed Challouf highlights its second renaissance under the revolutionary auspices of Thomas Sankara, president of Burkina Faso, the host country, from 1983 to 1987. Shot in 1999 on the occasion of FESPACO’s 30th anniversary, Challouf’s documentary weighs in on the significant changes that followed Sanakara’s assassination and the subsequent death of his pan-African, anti-imperialist utopia, which led directors like Haile Gerima to boycott the festival. Also included in the program was yet another gem from the late Med Hondo, undoubtedly one of the great modernists of world cinema: Les Bicots-nègres, vos voisins (“Arabs and Niggers, Your Neighbors,” 1974). Tragically relevant, especially in relation to the festival’s host country and its relapse into overt fascism, Hondo’s film farcically stages a very topical issue: the division along ethnic lines of the working class. The film is divided into multiple vignettes on the conditions of migrant workers in France, which the director never pities or idolizes, with African filmmakers featured discussing how to liberate their practice from the neocolonial nature of the film industry. Though set in France in the mid-’70s, the film’s lucid analyses, never burdened by a didactical tone, couldn’t feel timelier now that identitarian nationalism has toxically infiltrated mainstream political thought once again. But Les Bicots-nègres’ brilliance is not limited to its political dimension (which includes a thoughtful dissection of the political economy of African cinema and its subordination), and its multifaceted nature still stuns the spectator after almost half a century later.

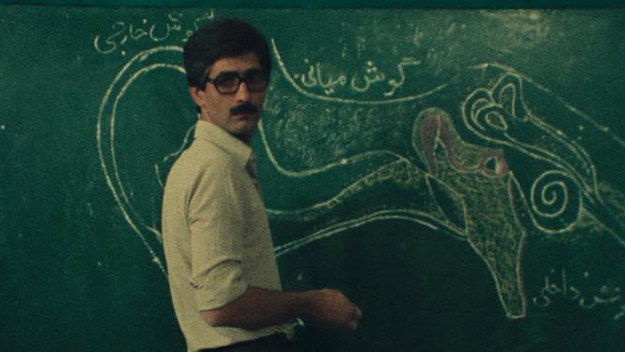

Much publicized on the eve of its projection, the long-banned and rarely seen Abbas Kiarostami film First Case, Second Case (1979) lived up to the understandable hype. A work of subtle political intelligence, this cinematic ruse explores the contradictory nuances of the Iranian Revolution without ever addressing the subject directly. The narrative pretext for Kiarostami’s reflection is provided by a classroom incident in which a teacher expels a whole row of students after they refuse to name the culprit behind a recurring prank. The events are then presented to the school children’s parents and a series of notables (including the spokespersons for the Jewish and Christian communities) for their evaluation. The director asks each person whether it is fair to expel a group of children and allow them back only on the condition that they name the person responsible for the prank. Should they, in the name of order and collective discipline, give their classmate away or remain silent? From their answers the Iranian director fashions a nuanced commentary on the dynamics of a revolution that was literally unfolding as the film was being shot—a revolution animated by different political currents and yet soon to be monopolized by clerical hardliners. As always, Kiarostami explores the layered complexity of the human condition and its endeavors with disarming simplicity and a profound sensitivity which needs no additional explanation.

First Case, Second Case ( Abbas Kiarostami, 1979)

Auteurist infatuations aside, Il Cinema Ritrovato again showed that the role that cinema can and did play in history is reason enough to deliver it from the neglect and condescension of posterity. The program “‘We Are the Natives of the Trizonia’: Inventing West German Cinema, 1945–49” offered a fascinating insight into how the collective (un)consciousness of the recently defunct Third Reich dealt with its own legacy. Unlike their former allies south of the Alps who cleansed their dirty consciences through Neorealism, Germans have admittedly faced, if not the roots, at least the legacy of the horror they collectively contributed to, either passively or proactively. The revived films constituted a first look at the country’s long process of reckoning with Nazism and taking responsibility, which has partly degenerated into a cultivation of guilt and in turn been followed by counterreactions. Right from the very beginning, the national stance on this history was anything but unanimous. Two films incarnate this split attitude: Helmut Käutner’s In Jenen Tagen (Seven Journeys, 1947) and Josef von Báky’s Der Ruf (The Last Illusion, 1949). The former, narrated by a talking car wreck that reminisces about wartime through a voiceover, illustrates the preposterous audacity with which sections of the German population looked back in awe and surprise at the unspeakable crimes of Nazism which had apparently occurred unbeknownst to them. The latter instead denounces a phenomenon little known outside of Germany: the abominable way in which German Jews were “welcomed back” from their exile. A film of profound intellectual honesty (the likes of which Italian directors have never produced after World War II), Josef von Báky’s film is a painful reminder of the difficulties in eradicating what was until a few years earlier the institutional norm.