Festivals: Chicago

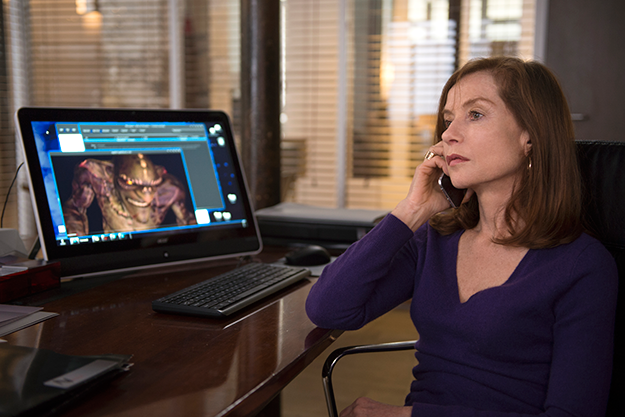

Elle

At the exact midpoint of this year’s Chicago International Film Festival, Paul Verhoeven’s Elle played to a sold-out theater in one of the largest of seven screens the festival commands for two weeks in the downtown AMC complex. Two-thirds of the folks in those seats seemed to anticipate the kind of hard-charging yet sophisticated provocation one might expect from Verhoeven and Isabelle Huppert. This crowd traded favorite extracts from Cannes reviews before the lights went down and debated how self-aware Showgirls really was.

The remainder of the audience comprised the kind of well-dressed enthusiasts who come every year to CIFF (as we locals call it), less versed in auteurist legacies but committed to supporting the arts, broadening cultural horizons, and sustaining Windy City institutions. Some of these patrons, convinced they were seeing a film called Ellie, were all the more shocked by the brutal opening scenes but remained palpably transfixed for the next 130 minutes—zero walkouts. One such viewer, a handsome woman of about 70, sat five seats down from me, laughing as nervously and gasping as loudly as I was. When the first end credit appeared onscreen in the dark auditorium, and with a look of rapt, thoughtful astonishment still on her face, she pulled an iPhone from an expensively lined pocket, opened a browser window, and stage whispered to the entire theater, “In case you’re wondering, the Cubs just won!” It wasn’t even the World Series yet. A few outraged aesthetes turned up their noses. Most people just clapped.

Much about this episode encapsulates my 11 years of attending CIFF, the oldest competitive film festival in North America but disappointingly underreported beyond Lake Michigan. Audiences turn up ready for challenges and pledged to an ethos of internationalism and imaginative daring. They don’t stop being Chicagoans, however, with some of the attendant hometown obsessions, and often a Midwestern skepticism about slow cinema or movies that feel “too weird.” Still, even the most outré titles play to packed houses, with patrons who never heard of Film Comment often taking more chances on less heralded titles and directors than the cinephiles rhapsodizing over Criterion’s new Dekalog set. People of all stripes crave early glimpses at Jackie or Moonlight or A Quiet Passion or I, Daniel Blake, the former two showing with their directors in attendance. Just as many, though, are excited to pick between two Polish musicals, Agnieszka Glinska’s Game On (16) or Janusz Majewski’s The Eccentrics (16); or to support the Chicago actors and artists who made the offbeat caper comedy Imperfections (16), which had its world premiere in the U.S. Indies section; or to gamble on whatever Finnish, Egyptian, or Filipino movie happens to be playing down the hall from The Accountant and looks 20 times more interesting.

Sieranevada

Beyond luring different types of viewers, CIFF works hard to ensure that the program—141 features and 45 shorts this year, from 50 countries—is truly designed for them. Every October, CIFF stitches itself into the life of this thriving American city, much the way Toronto’s larger and more famous festival does. CIFF’s ticket prices, however, hew closer to average multiplex rates, and no phalanx of publicists, bigwigs, and global press intercedes between the artworks, the artists, and their admirers. CIFF lacks the cavalcade of high-profile premieres one finds at other autumn institutions like Venice or Telluride or Toronto, but it introduces meat-and-potatoes Chicagoans to several marquee titles from those festivals and from Cannes, Berlin, and others as well.

Furthermore, as has been true since Michael Kutza launched CIFF in 1964—and, 52 years later, he remains its artistic director—the event furnishes a robust showcase to emerging talents from around the world, not just of established auteurs. CIFF has nurtured future household names from Martin Scorsese to Asghar Farhadi, each of whom won competition slots (Scorsese for Who’s That Knocking on My Door?, still titled I Call First) and jury awards (the Golden Hugo for Best Film went to Farhadi’s Fireworks Wednesday in 2006) before other major festivals took much notice. Audiences thus have good reason to trust these programmers’ assurances that up-and-coming names like Anne Zohra Berrached, Mijke de Jong, Carlos Lechuga, or Shahrbanoo Sadat are well worth tracking. Few of these can be claimed as the Chicago programmers’ own discoveries; the controversial lack of a sales market at CIFF can also work against rookie filmmakers who are seeking traction with distributors. The festival remains a staunch advocate, though, for directors who keep returning and others getting a first shot; for the principle of putting audiences first; and for “smaller” titles that didn’t dominate headlines wherever they premiered but certainly deserved to—sometimes more than the movies that did.

This year’s Main Competition jury, chaired by the effervescent winner Geraldine Chaplin—who also received a career tribute at Andersonville’s Essanay Studios, where her father made 14 movies—largely favored titles that already made vibrant marks at earlier venues. Cristi Puiu won the Best Feature and Best Director awards for his Cannes sensation and sequence-shot tour de force Sieranevada, which recently topped Film Comment’s contributor poll as the best undistributed film of 2016. It thus joins a tony roster of recent CIFF champions including Hunger (08), Mississippi Damned (09), Holy Motors (12), and My Sweet Pepper Land (13). The fact that two of these never secured a commercial run in the U.S. proves that CIFF has limitations as a launching pad, but also that more attention ought to be paid, given the consistent caliber of its choices. Farhadi’s The Salesman, Cristian Mungiu’s Graduation, and Antonio Campos’s Christine also won prizes for performances, screenplays, and overall craftsmanship this year.

24 Weeks

As usual, though, much of the excitement lay outside the winner’s circle and off the radar of previous festival buzz. The most hypnotic fiction feature I saw was Berrached’s 24 Weeks, about a German stand-up comedian forced to consider a late-term abortion well after her pregnancy has been trumpeted to fans on celebrity news sites. Berrached’s movie, anchored by Julia Jentsch’s meticulous and quietly forceful performance, is the rare pregnancy drama to focus even more on a woman’s mind than her body, rendering the option to abort not as one consolidated do-or-don’t decision but as a web of multiple, overlapping, carefully weighed quandaries. It offers complex portraits of multiple characters in her domestic sphere without hedging on whose story this finally is, and follows a narrative track that feels at once implacable and unpredictable.

24 Weeks played in competition at Berlin last year but elicited less press than it deserved. Actor Bjarne Mädel, a well-known German comic doing rich, sober work as Jentsch’s husband, confided at the post-film Q&A that Berlin jury president Meryl Streep effusively congratulated the filmmakers after a screening and immediately followed with, “You know they will never release this movie on this topic in the US, right?” Thus far, Streep’s prophecy has proved correct. Booking 24 Weeks, then, was a great and prototypical CIFF move: cherry-picking beyond the most obvious titles at other world forums while also standing up for a new talent taking major, virtuosic risks that may limit her work’s visibility.

Chicago spotlighted several other features by young writer-directors that, like 24 Weeks, played to acclaim at earlier fests but merit bigger buzz and await U.S. distribution. One of these was Sadat’s Wolf and Sheep, a beguiling mix of documentary and surrealist dream about sheepherding children in the Afghani mountains and a shapeshifting phantom who haunts their village after dark. Panamerican Machinery, which played in the Forum at Berlin, is a sad but strangely droll tale about workers and middle managers who refuse to leave the factory after their company president collapses and dies. Suggesting Yorgos Lanthimos south of the border, the movie feels increasingly timely for U.S. audiences, both as a snapshot of a newly leaderless community in a fugue state of ambivalent grief and as a perverse redrawing of Trumpian fantasies: what if Mexican laborers built a wall around themselves and nobody paid for it? The Kenyan-German coproduction Kati Kati, cited by FIPRESCI for a Discovery award in Toronto, also surveys a social body in a strangely suspended state, gradually revealing itself as world cinema’s most sun-splashed vision of purgatory. Maybe an elliptical, 75-minute feature in Swahili sounds unthinkable as a commercial prospect, but this streamlined, creative, gorgeously lensed feature resembles a sub-Saharan mashup of Lost, 28 Days Later, and The Leftovers and is as accessible as any of those three.

Finals

Speaking of leftovers, though, not every film at CIFF arrives secondhand. Quite to the contrary, the festival hosts an impressive number of premieres, which this year included the very first screening of the Iranian feature Finals, one of Abbas Kiarostami’s final screenwriting credits. Directed and co-scripted by Adel Yaraghi, the movie stars The Salesman’s Shahab Hosseini as a high school teacher trying to help his girlfriend’s petulant son cheat his way through an exam. Yaraghi doesn’t yet ratchet tension as nimbly as Farhadi does or govern image and montage as ingeniously as Kiarostami did, but he is getting there; the film compels as more than just a master’s final memento. A more engrossing Iranian effort was Parviz Shahbazi’s Malaria, a high-velocity lovers-on-the-lam thriller screening for the first time in North America. The story has complicated sympathies, a killer ending, and a handful of peripheral characters who could easily anchor their own films.

The nonfiction sections of CIFF—a longstanding strength of the festival, and all the more so under new programmer Anthony Kaufman—also unveiled a series of impressive new works. The winner of the Gold Hugo for Best Documentary was Pieter van Eecke’s Samuel in the Clouds, a North American premiere whose title figure is the operator of the world’s highest ski-lift, on a Bolivian glacier. Samuel Mendoza, his old age chronicled as indelibly as the youth of the Lampedusan kids in Fire at Sea (like Elle, a special one-night presentation at CIFF) is starting to slow down. His wife worries he will fall off the ridge while walking to work, as happened to Samuel’s own father, who previously managed the lift. Even more drastic, though, is the decline of the Chacaltaya peak. The most devastating single cut at the festival was from footage of a recent start-of-ski-season celebration on the mountaintop, with indigenous Bolivians in colorful robes dancing amid the snowdrifts, to a shot this year from the very same angle, on what is now a parched, sun-baked hillside. This 70-minute portrait of climate change, also oriented through the patrons of the ski lift and the scientists studying the probably unsaveable glacier, is all the more harrowing for being so intimate and humane.

Chicago’s tradition is that only documentaries without secured distribution are eligible for prizes, which hopefully function as calling-cards for adventurous companies. They had much to choose from here, including another North American premiere, Girls Don’t Fly, about a Ghanaian aviation academy for female teens. This quietly clear-eyed study steadily exposes the school, putatively opened as a philanthropic endeavor by a white British flying buff, as something closer to a martinet camp and cruel hoax. A Mere Breath, handsomely and patiently shot over seven years, profiles a Romanian family whose patriarch hopes his assiduous prayers to God will cure his adolescent daughter’s spina bifida. Filmmaker Monica Laurean-Gorgan is too compassionate to treat this earnest man as a naïf or a zealot, but the rest of the family radiates skepticism, including an older son who seems to fall by the wayside of his father’s attentions in their economically depressed town.

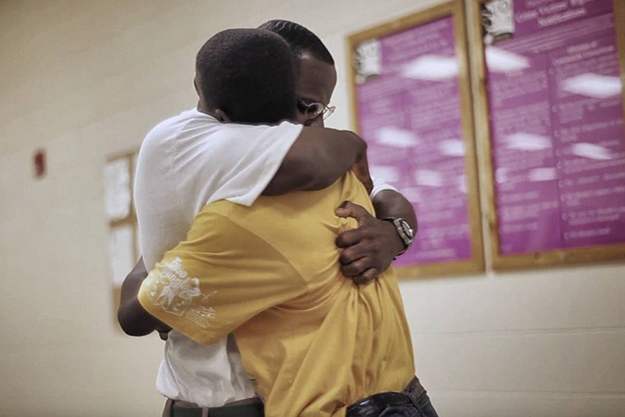

Raising Bertie

The two most essential movies I saw at CIFF were documentaries that had already lined up distribution but are so politically timely and artistically consummate that they warrant all the attention they can get. Each also sported strong local connections. Kartemquin Films, the Chicago-based production company renowned for its investment in class politics and social justice, from The Last Pullman Car (83) to The Interrupters (11), offered an early sneak on its 50th birthday of Raising Bertie, hopefully reaching U.S. screens in 2017. A sort of Hoop Dreams without the hoops, Bertie immerses itself for several years in the lives of three black male high school students in impoverished Bertie County in rural North Carolina. Community centers open, close, and fight for new homes. Jobs and fathers and college prospects come and go. One man and his girlfriend enjoy a hard-earned night of dancing and fancy dress at their senior prom, then come home to feed their baby and look nervously, as ever, toward the next day. With electoral rights and various minority identities so besieged in North Carolina, and with “economic anxiety” somehow gerrymandered as an exclusive concern of working-class whites in our media discourse, this focused and nuanced look at a resilient but deeply strained African American township carries urgent implications for all of us.

Craig Atkinson’s Do Not Resist, a 73-minute indictment of the militarizing of U.S. police and the flows of government money and power that ensure it, differs from Raising Bertie in almost every point of style and rhetorical pitch. Atkinson shot and co-edited his own movie over two years and almost a dozen different states, spanning the riots in Ferguson, Missouri, the videotaped execution of Laquan McDonald that continues to roil Chicago, and the pastoral New Hampshire and Wisconsin towns that suddenly find Humvees and Bearcats prowling their streets. Do Not Resist, the most brilliantly mixed and photographed political documentary since Iraq in Fragments, literally and figuratively makes this country look a lot like that one. Having earned the top prize at Tribeca, the movie should have been booked in every theater in America, rather than just the sixteen cities that screened it commercially this fall, with muted fanfare. CIFF programmed the film with an extended Q&A encompassing Atkinson, his producer Laura Hartrick, and activists with expertise on gun violence, policing, and their social contexts. The Chicago International Film Festival is a major boon and service to its city every year, but never more so, however solemnly, than on an evening like this.

Nick Davis is a professor of film, literature, and gender studies at Northwestern University. He also writes film reviews at www.NicksFlickPicks.com.